Local-level campaigning has made a comeback. For decades, many election scholars viewed canvassing for votes as an antiquated holdover from the pre-electronic age of stump speeches and pamphleteering. As a result, local-level campaigning attracts relatively little scholarly attention. But in recent years, there has been growing interest in the work of candidates and their supporters, in particular by political parties.

To most observers of elections in Canada and elsewhere, the dominance of broadcast media and national campaigning diminished the perceived relevance of what happens in the 338 defined geographical areas that members of Parliament (MPs) represent in the House of Commons. To these cynics, electioneering by candidates and their supporters in electoral districts – also known as ridings or constituencies – was both perplexing and irrational.

Skepticism intensified in the late 20th century with the proliferation of 24-7 television news, coupled with the emergence of fax machines, email, websites and a permanent electronic list of electors. These technological changes paved the way for more centralized co-ordination by political parties that dispensed with direct, local contact with electors in favour of co-ordinated, national-level indirect communication, often via news management and advertising in the mainstream media. Gradually, local candidates were subsumed into a party brand dominated by the leader’s personality and by media interest in the national leaders’ tour.

Some of the most hardened skeptics of constituency campaigning were (and remain) political scientists who, since the 1940s, have used public opinion survey data to establish the prevalence of national-level variables over local factors. To them, knocking on doors is quaint but rather ineffective, and constituency campaigns are meaningless rituals. Research studies finding that a political party’s candidate accounts for between zero to 10 per cent of the vote – with incumbents and rural candidates at the upper range – have repeatedly affirmed the primacy of the national campaign. Constituency campaigning was left for dead by all but its enthusiasts.

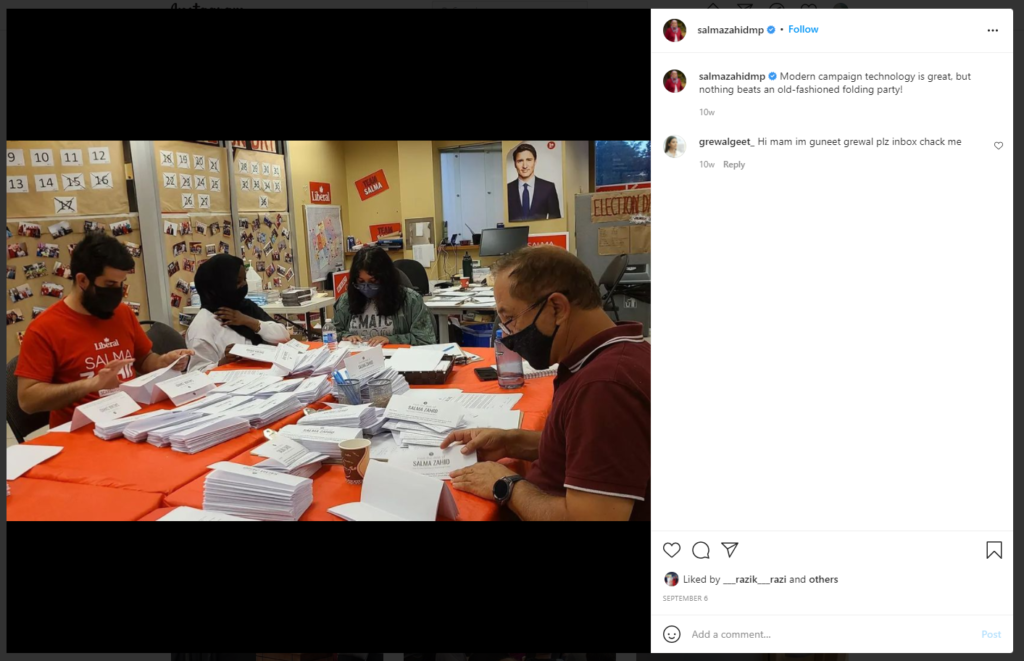

Things evolved in the 21st century with innovations in communication technologies. Suddenly local-level campaigning was fashionable, even as candidates morphed into brand ambassadors while decision-making became increasingly centralized in party war rooms. Between and during elections, political parties harnessed web and mobile technology to assemble databases that house information about electors, which they use to deploy cost-effective, targeted canvassing and messaging in a highly competitive electoral marketplace.

National parties urge incumbents, candidates, local party workers and volunteers to compile intelligence about constituents that is uploaded instantly into party databases, and sometimes into an MP’s own private database. The surge of interest in the ground game has coincided with a drift away from national-level broadcast advertising towards the microtargeting of electors through more precise and narrow social media ads. This co-ordinated management of “big data” has both centralized and energized local campaign outfits. The embrace of digital communications is one of the many reasons why constituency campaigning in Canada warrants scholarly attention.

Political scientists who study political behaviour tend to discount the effectiveness and rationality of constituency-level campaigning. Their analysis of public opinion data consistently demonstrates the primacy of partisanship, socialization, leaders and other macro-level variables, reflecting a stark reality that for most Canadians, there is little payoff in investing effort to assess individual candidates in a political system where elected officials toe the party line.

Consequently, constituency campaigning is often viewed as little more than a ritual that is inconsequential to the election outcome. Candidate factors are estimated to matter most for partisans, and to make the difference between winning and losing in only 10 to 14 per cent of electoral districts. There is scholarly consensus that constituency campaigning really matters only in close races where there is increased voter interest and turnout, less effort required by voters to find information about candidates, and a greater presence of party resources and tactical voting.

It is true that constituency campaigning is often a dubious use of time and resources if it is purely to generate votes. In some safe seats, the victory of a party’s candidate can reach a margin of more than 70 per cent of the vote compared to the runner-up. Where local campaigning truly has an electoral impact is in ridings where winning and losing is decided by a few hundred votes or less. Prevailing in a suite of close races makes the difference between forming a majority or minority government, or between forming a minority government versus sitting on the opposition benches. As well, candidates who secure a higher share of the vote, who build a local profile and who make connections can generate positive news stories, be seen as opinion leaders and augment their status within the party.

In any event, elections are about so much more than getting candidates elected. Constituency campaigning is a fundamental democratic function that activates, engages and includes electors and party workers in the process of selecting a representative, deliberating public policy and indirectly selecting a prime minister and government. It causes politicians to personally interact with constituents, to listen to their concerns and to integrate members of diverse communities who might ordinarily feel left out of politics.

Indeed, many candidates have no chance of victory, meaning that they and their campaign workers are motivated by a sense of loyalty, promoting a political ideology and the allure of social comradery that boosts supporter morale. Their engagement instills a sense of identity and belonging. When the victor is declared, winners are congratulated for a strong campaign, while losers attribute defeat to factors beyond their control.

All types of candidates and canvassers recognize that talking to electors in person at their homes is one of the best ways to identify potential supporters, particularly given that telephone canvassing is complicated by people screening their calls and by the abandonment of landlines. Today’s constituency campaigners are not focused on identifying the vote only for “get-out-the-vote” operations. They are also canvassing for data that can also be used post-election for fundraising appeals and relationship-building as part of the permanent campaign. In some parties, a group of canvassers knock on doors, hurry the candidate over to greet a constituent and record information on a smartphone or tablet. Increasingly, the canvassers who continue to visit residences armed with a pencil and clipboard are the ones participating in a ritual.

Despite their increasing importance as data collectors, or perhaps because of it, party candidates have continued to submit their public identity to their party and to a leader who is centre stage in everything from the party’s manifesto to advertising to the leaders’ debates and the leader’s tour. Local campaigns may be required to provide funds toward party advertising and relinquish as much as 100 per cent of their post-campaign spending rebates to the national party. At its discretion, the party can also deny candidates and MPs access to the local data they collected about party members and supporters. On rare occasions, we see instances of local flagbearers being championed by the party, as occurred with Liberal advertising in the 2021 federal election that featured Quebec candidates talking about how “Team Trudeau is a tightly-knit team with a united vision.” All of this attests that the relationship between candidates and their parties is more complex and mutually beneficial than may appear – and why Canadian research should stop ignoring local campaigns.

Cet article présente une version abrégée d’un chapitre tiré d’un ouvrage qui sera publié en 2022 chez UBC Press. Il fait partie du dossier spécial Au cœur d’une campagne de terrain.