C .D. Howe. Mitchell Sharp. Donald Macdonald. Charles “Bud” Drury. Edgar Benson. Don Johnston. Robert Winters. Bob Andras. Paul Martin. John Manley. Doug Young. Roy MacLaren. Anne McLellan.

Some of these names are long forgotten; others remain in our collective political memory. All were once prominent members of a species known as “business Liberals” or “blue Liberals”; Don Johnston once described himself as a “blue Grit.” Business Liberals flourished and occasionally dominated in the governments of Louis St. Laurent, Lester Pearson, Pierre Trudeau, Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin.

The breed seems to be extinct in Ottawa today. And this is a problem.

The federal Liberals are often considered the archetypal brokerage party, if not the world’s most successful practitioners of the brokerage craft. By this I mean they are skilled at coalition building across different interests within a political party that contains a wide range of views.

The Chrétien government was a good example. During Chrétien’s first mandate as Prime Minister, his caucus consisted of a broad mix of outlooks and ideologies, from social democrats like Charles Caccia at one end of the spectrum to social conservatives (a group of MPs known as “the God Squad”) at the other, and everything in between. These varied interests were successfully brokered to ensure the government remained functional, stable and effective.

Historically, business has been an important brokered interest within Liberal governments. Canadian business has normally had a voice, respect and power at Liberal cabinet tables through the so-called business Liberals. These people were often in business themselves before becoming politicians. Some were lawyers who had business clients. Many had an appreciation and respect for the challenges of the business owner, manager or executive, in small, medium-sized or large firms. All thought a lot about the economy and the government’s impact on business through its trade policy, tax policy, broader fiscal policy and regulation.

These ministers and this world view mattered in Liberal governments — within the cabinet, in the caucus and across the civil service — for decades. The business Liberal perspective didn’t always or even mostly prevail in policy-making, nor should it have. But it was represented forcefully and considered seriously in the mix.

As a young ministerial staffer in the mid-1990s, I watched the business Liberal wing of the Chrétien cabinet move to dominate a government that I naively thought was headed in a centre-left direction.

As a young ministerial staffer in the mid-1990s, I watched the business Liberal wing of the Chrétien cabinet move to dominate a government that I naively thought was headed in a centre-left direction. In those days, their point of view carried a lot of weight — and for good reason, as the chief policy challenges were economic and fiscal. Ottawa was staring down the twin evils of a deficit crisis and double-digit unemployment.

A minority in the cabinet, the business Liberal ministers nevertheless occupied key positions, notably Finance (Martin), Industry (Manley), International Trade (MacLaren), Transport (Young) and Natural Resources (McLellan). It was difficult enough for the Prime Minister and the Finance Minister to tackle the deficit aggressively in those days. It would have been harder still without a few forceful business Liberals around the table backing them up. Doug Young, for instance, largely forgotten now but a force of nature in those days, embraced the dismantling of a large part of his portfolio in pursuit of the broader business Liberal agenda of deficit reduction, deregulation and privatization.

This strong business voice in past Liberal governments had three main purposes. First, to focus on economic and fiscal policy, to understand and appreciate business concerns and priorities, and sometimes make a case for those at the cabinet table. Second, to have meaningful and trusting relationships in the business community that could be drawn on to reassure business about the broad direction of the government as well as on specific policy initiatives, and to sometimes road-test government ideas. And third, to listen and speak to business in a language they understood — to empathize, if you will.

The business community knew that within those governments there were ministers with gravitas who were concerned chiefly with the economy’s performance and had the back of business, as well as the voice and power to bring business perspectives to the cabinet table in an influential way. This is what business Liberal ministers did.

If you talk to people who represent business interests in Ottawa today and have regular interaction with the federal government, you will be hard pressed to find anyone, in any sector of the economy, who thinks those kind of ministers exist anymore. The business Liberals of old seem to be extinct, presumably because their perspective is not valued the way it once was.

The business community, as represented by its various associations and spokespersons, has applauded the Trudeau government’s effort to secure a renegotiated NAFTA that does no harm to Canadian business. But beyond that file there isn’t much this government gets credit for from business. At the same time, there is a mountain of policy criticism from the business constituency — and not just from the oil and gas industry, which is well covered in the media, but from virtually all sectors touched by the legislative arm and regulatory hand of the federal government.

A general sense exists within the organized business community that the Trudeau Liberals are at best indifferent to business and its interests, if not ignorant of them, and at worst hostile to the business mind and orientation. The government is often seen by business as being far more inclined to listen to and be influenced by the non-governmental organization or “civil society” perspective — including in policy domains that directly affect business — than by the business view.

There is no senior minister in this government, much less a group of important ministers, who is thought by the business community to be focused on the impact of government policy on business, and who possesses the clout, and the willingness to use that clout, to take the business view forcefully to the cabinet table and the Prime Minister’s Office. In other words, there are no “go-to” ministers for business in this government.

This is a problem, especially as business faces unsettled times in the short term, and a longer term in which Canada moves toward a fundamental transformation to a less carbon-dependent economy, which will affect virtually all business.

The business community, including both its organized advocates and individual companies, does not have the market cornered on good public policy ideas. Far from it. Its proposals are often unworkable or not in the public interest. Some are fatuous.

That said, business knows more about how public policy decisions affect it than any public servant ever will. For that reason alone, business Liberals are needed at the cabinet table. Liberal prime ministers in the past recognized this need and provided for it. The policy process was enriched as a result. Prime Minister Trudeau and his people need to better appreciate this basic feature of Liberal government success and regenerate the business Liberal species.

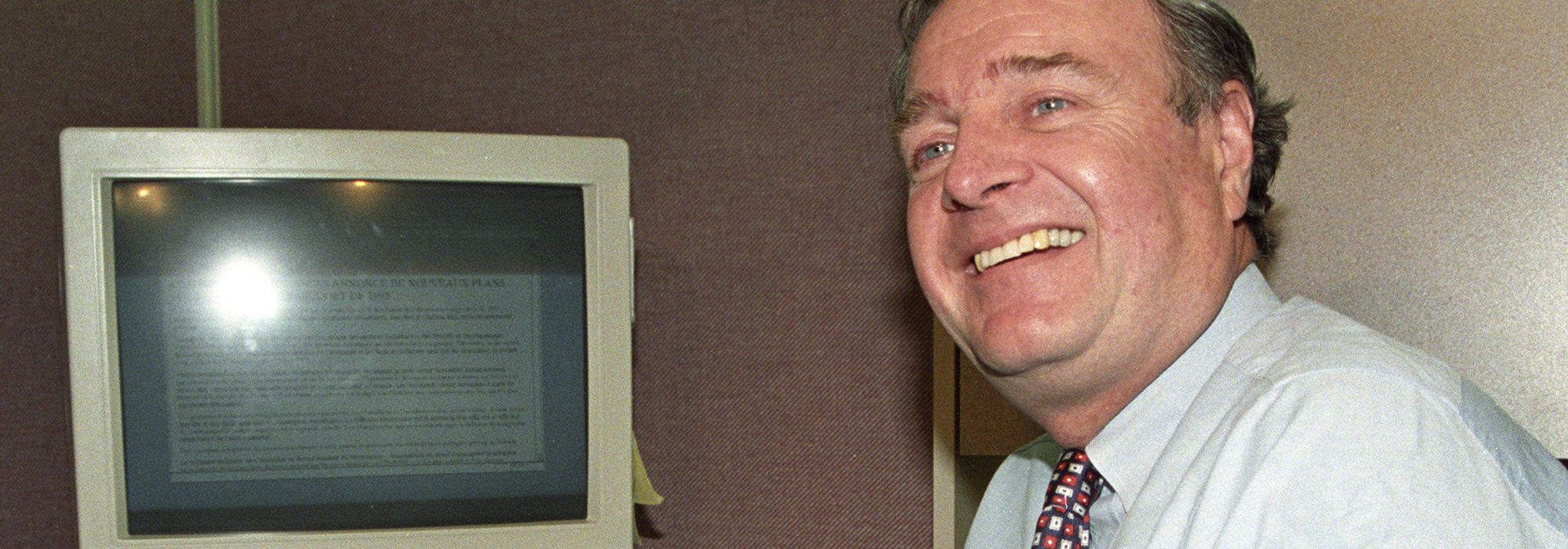

Photo: At a January 1995 press conference in Ottawa, Finance Minister Paul Martin talked about how his federal budget for that year would be available on the Internet. The Canadian Press/Tom Hanson

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.