Official documents prescribing mass surveillance, mass internment and mass forced sterilization. Satellite imagery documenting the destruction of ancient cultural sites and the proliferation of concentration camps. Products made using enslaved Uyghur labour, and some made from the hair of interned Uyghur women. Drone footage showing men — heads shorn, shackled and blindfolded — being herded onto trains.

These are just some of the glimpses the world has had of a genocide unfolding in real time in East Turkestan/Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, despite the cone of secrecy China has placed around it. The secrecy makes it impossible to even know for sure exactly how many millions have been incarcerated in what is suspected to be the largest regime of minority internment since the Nazi Holocaust. It is estimated that more than 1 million Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslim minorities have been detained since 2016.

Leaked official documents such as the recent Qaraqash List reveal Uyghurs having been imprisoned for such “offences” as applying for a passport, having multiple children, visiting abroad, growing a beard, wearing a headscarf, abandoning alcohol, abstaining from cigarettes and other markers of Islamic religious observance.

This is just the latest stage in China’s centuries-long project of settler colonization and demographic change in the resource-rich territory China refers to as “Xinjiang,” literally meaning “new frontier.” The renowned scholar of settler colonialism Patrick Wolfe famously wrote that “the question of genocide is never far from discussions of settler colonialism.” In the case of China’s policies against the Uyghurs, this question of genocide is not just abstract or metaphorical, but imminent and literal.

In the UN Genocide Convention and the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC), genocide is defined as any one of five acts — 1) killing; 2) causing serious bodily or mental harm, including rape; 3) infliction of conditions calculated to bring about physical destruction; 4) imposition of measures intended to prevent births; or 5) forcible transfer of children — when conducted with an intention to destroy a people as a people, in whole or in part.

Any one of the listed acts qualifies as genocide when committed with the requisite intent. In the case of the Uyghurs, there is evidence of all five categories of genocidal acts having been inflicted.

There are reports of deaths and disappearances in concentration camps; psychological and physical tortures such as brainwashing, electrocution and waterboarding; sexual violence against Uyghur women, including through forced cohabitation and intermarriage with the dominant Han Chinese group; forced starvation and exposure to diseases, including coronavirus, in concentration and labour camps; a sterilization campaign in which 80 percent of new birth control devices in China were installed in Xinjiang, which contains less than 2 percent of the population; and the separation of almost half a million children from their families and communities.

As for the question of intent: when officials describe Islam as an “ideological virus,” an “incurable malignant tumour,” and a “weed” infiltrating the “crops,” efforts at eradication are the logical extension. There will be “absolutely no mercy,” Chinese President Xi Jinping has said. As Chinese professor and military science adviser Ai Yuejin stated in a lecture at Nankai University for military students, “We change and accept the good races into our own society and torture and eradicate the bad ones.”

Underscoring the seriousness of the crime, the Genocide Convention includes not simply an obligation to punish genocide after the fact, but an obligation for all states to prevent and stop it. According to a 2007 decision of the International Court of Justice, “a State’s obligation to prevent [genocide], and the corresponding duty to act, arise at the instant that the State learns of, or should normally have learned of, the existence of a serious risk that genocide will be committed” (paragraph 431; emphasis added).

That threshold of “serious risk” has surely long been passed. In 2014, the UN Office on Genocide Prevention released a framework for identifying warning signs of genocide and other atrocity crimes. Virtually all are present in Xinjiang.

Canada must also ban all products of enslaved Uyghur labour, and ensure that no Canadian corporations are complicit in or profiting from the genocide.

On July 20 and 21, Canada’s parliamentary Subcommittee on International Human Rights heard from panels of Uyghur survivors, legal and policy experts, and academic specialists regarding the situation in Xinjiang, the history of China’s policies of persecution in the region and what Canada can and must do. The subcommittee will release its report on August 14.

Such hearings are just one preliminary step toward fulfilling Canada’s obligations under the Genocide Convention.

Canada should recognize the situation as genocidal — acknowledging that the duty to prevent has been triggered — and impose sanctions under the Magnitsky Act on all officials and entities involved. A complaint filed with the ICC by two Uyghur organizations in exile names more than 30 Chinese officials responsible, including President Xi Jinping.

Canada must also ban all products of enslaved Uyghur labour, and ensure that no Canadian corporations are complicit in or profiting from the genocide. For example, Canadian company Bombardier was identified alongside 81 other global brands implicated in forced Uyghur labour in a damning report from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute; Canada-based mining company Dynasty Gold operates a gold mine in Xinjiang; and the Canada Pension Plan is a major shareholder in Chinese technology company Tencent, accused of carrying out surveillance and censorship against the Uyghurs.

As the United Nations Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar has warned, “International law … permits States to hold company officials criminally liable for their direct acts or omissions … if they aid, abet or otherwise assist in genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes … If businesses rely on the services or resources of the States or encourage the State to provide it with services and resources, with the knowledge that these services might result in crimes under international law, the relevant business officials risk criminal liability.”

Finally, Canada should also support international legal efforts to achieve accountability. Such opportunities are limited by the fact that China is not a State party to the ICC and rejects the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice regarding breaches of the Genocide Convention. However, the ICC’s decision in the Rohingya genocide case that it does have jurisdiction over crimes spilling over onto the territories of other State parties — even if the State perpetrating them is not a party itself — may provide a legal foundation for a criminal case against China. This is the basis of the aforementioned complaint lodged by the Uyghurs at the ICC.

In responding to the Uyghur genocide, it is not only China’s conscience and legal obligations that are at stake, but those of Canada and the international community as a whole.

Yet governments persistently resist using the term “genocide” — as if by avoiding the word they avoid responsibility for the reality. Many states, including Canada, delayed recognizing the Rohingya genocide, which is now before both the International Court of Justice and the International Criminal Court. States previously refused to recognize the Rwanda genocide as it was unfolding before the eyes of the world in 1994.

Even in the face of overwhelming evidence, the capacity for denialism is great. As are the shame, repentance and horror in hindsight when “never again” is permitted to occur again and again.

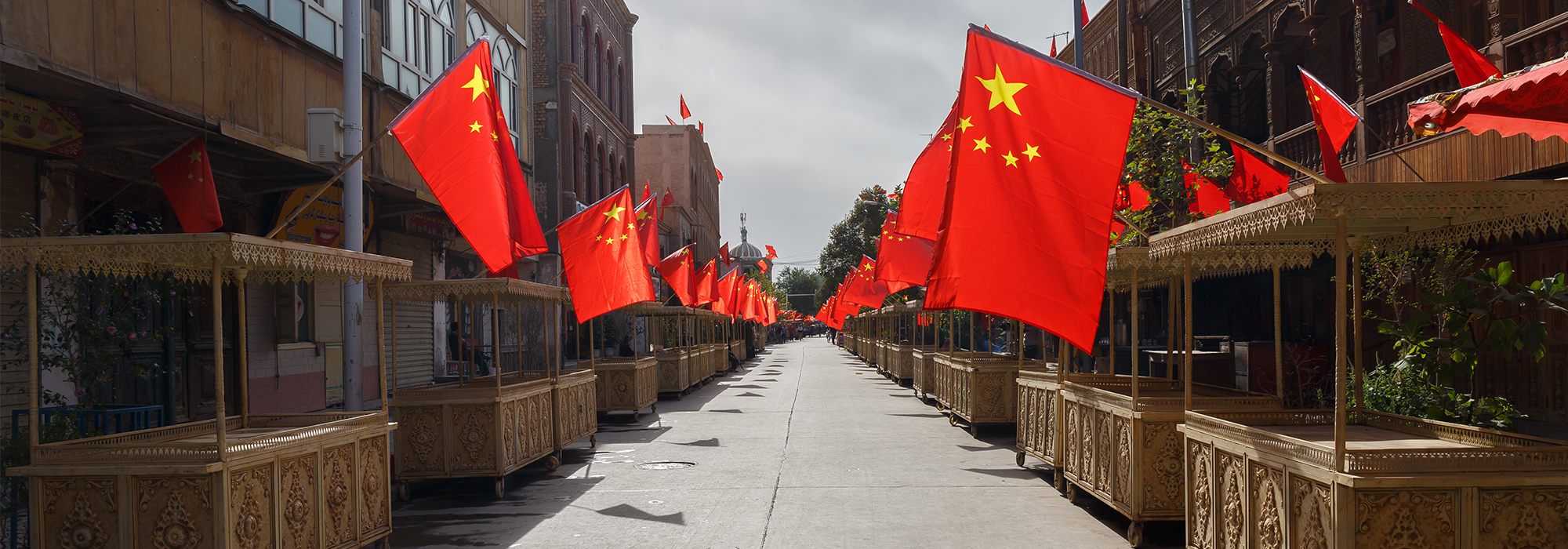

Photo: Chinese flags fly over market stalls in Kashgar, Xinjiang, Western China, marking a Chinese national holiday in September 2017. Shutterstock/By Chris Redan