With the decision by the Supreme Court of Canada to hear the challenge to the five-year restriction on expatriates’ voting rights, it is timely to review the arguments in favour and against extending the time. In addition, we need a better idea of the number of Canadian expatriates abroad and the nature of their ongoing connection to Canada.

Starting with the number of Canadian expatriates, recent advocates have relied on the estimate from the Asia Pacific Foundation (APP) Canadians Abroad: Canada’s Global Assets of 2.8 million expatriates. This figure does not control for age or citizenship. When we do so (using the 2006 Census), the figure is just under 2 million (of whom 77 percent are aged 18 or over, and 78.1 percent of whom were immigrants had become Canadian citizens).

There is also a dearth of data on expatriates’ degree of connection to Canada, and what exists is based on anecdote rather than government data. Consular data for 2007 to 2015 show that approximately 20,000 expatriates annually accessed services for people who had been abroad for five years or more. The number of passports issued abroad was about 184,000 in 2015, and there were approximately 725,000 Canadian passport holders living abroad.

Looking at nonresident Canadians’ tax filing data, 136,310 returns were filed, which was 7 percent of the number of expatriates in 2013, the most recent year that complete data is available. While this figure may understate the proportion of nonresident Canadians filing taxes, as some may use Canadian addresses, it suggests that the vast majority of expatriates do not pay Canadian income tax. I have not seen any reliable data on nonresidents’ property taxes.

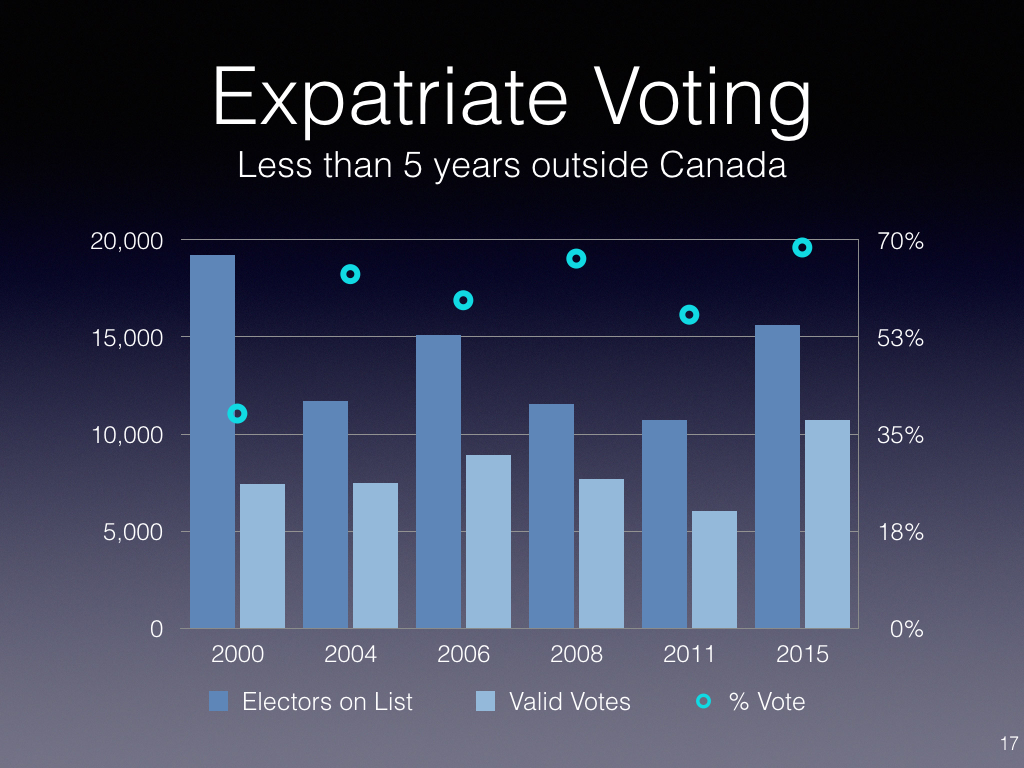

Data on voting among those who have been abroad less than five years indicates the number of expatriates who register and vote is very low. (This also applies to Canada as a whole: in 2015, out of a total of 26 million eligible voters 17.6 million voted.) Figure 1 shows the number of nonresident electors, valid votes and percentage of voter turnout for the last six elections. This data suggests that relatively few of those who have lived abroad for five years or less are politically engaged (of course, some may return to Canada to vote, but we do not have data on this).

The data we have, imperfect as it is, suggests that of the 2 million Canadian citizens living abroad aged 18 or over, the number who have ongoing active connections with Canada is likely quite low. Even advocates of expatriate voting rights, after citing the APF number of 2.8 million expatriates abroad, go on to quote the figure of “over one million” who have active connections, but they do not explain the basis for that number.

Arguments in favour of expanding the expatriates’ voting rights are based on the Charter’s protection of voting rights without qualification. The main substantive arguments, by the plaintiffs, by academics such as Semra Sevi, Peter Russell, Alison Loat and John McArther), and by former Global Affairs director general Gar Pardy, can be resumed as follows:

- Canadians living abroad contribute to Canada and the world, and many retain an active connection with Canada, whether it is business, social, cultural, political, or academic. These Canadians’ global connections should be valued as an asset;

- Patriotism and civic engagement are not tied to location;

- The internet and online communities make it easier for Canadians to remain in touch with Canada and Canadian issues;

- As Judge Laskin said in his dissenting statement in the July 2015 Ontario Court of Appeal ruling, Canadians living abroad pay “Canadian income tax on their Canadian income, and property tax on any real property they may own in Canada,” and are subject to Canadian laws and foreign policy decisions;

- As Russell and Sevi note, the expatriate vote will not “completely change the tide of an election.”

- The five-years-or-less limitation is more restrictive than those of other Western countries; for example:

- United States: no limitation, but expatriates are required to file US tax return;

- United Kingdom: the limitation is fifteen years;

- Australia: the limitation is six years, and expatriates must file an annual declaration of their intent to return at some point;

- New Zealand: the limitation is three years, and the clock restarts when citizens visit New Zealand.

- The Canadian five-year limitation ignores the increasing globalization and population mobility, and it sends the wrong signal to young Canadians;

- As Jean-Pierre Kingsley, former chief electoral officer, said when he advocated eliminating the five-year limit: “The right to vote is a fundamental right of citizenship that is protected by the Charter and does not depend on place of residence.” A parliamentary committee reviewed his report in 2006 and endorsed his position.

The principle arguments against are the following:

- The “social contract” argument, used by the Ontario Court of Appeal to uphold the policy, states that voting “would allow them [expatriates] to participate in making laws that affect Canadian residents on a daily basis, but have little to no practical consequence for their own daily lives. This would erode the social contract and undermine the legitimacy of the laws.” Examples of policies and programs that are considered part of the social contract include economic and social policies and programs, at the federal level; health care and education, at the provincial level; and policing and transit at the municipal level;

- While some expatriates may pay Canadian taxes and may own property in Canada, the data suggests over 90 percent do not, as they pay tax where they work and live;

- Interest in voting among expatriates appears to be low;

- Apart from consular and passport services, most Canadian government economic and social programs are tied to residency;

- In general, the longer the time spent abroad, the looser the bond with Canada, as family, work and local connections become more meaningful. Over time, day-to-day living — work, education, raising a family, consuming media — predominate important for expatriates, whether in the United States, Hong Kong or the Mid-East;

The Supreme Court will have to rule whether the right to vote is qualified by residence and the degree to which the social contract argument justifies certain limits.

Some of the advocates of expatriate voting, for example, Gar Pardy, argue for no limits, which Loat and McArthur also imply. Sevi and Russell imply limits, but ones that are more in line with those of other countries, but they do not indicate their preference.

To cite an extreme example of the “no limit” argument, Canadian expatriates born abroad (citizenship by descent) who have never lived in Canada would be entitled to vote, even if they had never set foot in Canada. A less extreme example is that of people born in Canada who move abroad as children and remain outside Canada. In both cases, it is hard to justify nonresidents having voting rights when they have spent no time or extremely limited time living in Canada.

The “comparability” with other nations argument is more reasonable and convincing, and opens the discussion as to which option — taxation, as in the United States, extending the limitation to 15 years, as in the United Kingdom, or renewable voting rights, as in New Zealand — makes the most sense from a policy and implementation perspective. I suspect most Canadian expatriates would not welcome linking voting to filing tax returns. It would go against long standing Canadian tax policy, and judging by US expatriates’ opposition to the over-reach of Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, this option is likely a nonstarter.

If the Supreme Court rules against the five-year limit, my preference, would be some variant on the Australian and New Zealand approach, i.e., allowing voting rights to be renewed but requiring some action by expatriate voters to extend their right, perhaps through a written declaration or periodic visit to Canada. This does not seem to be an unreasonable obligation, and it allows for mobility but requires a concrete and a relatively easy to administer test of the expatriates’ connection to Canada.

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.