Public art is not an indulgence. Cities are expressions of our culture, and public art has always played a role in defining that common space. But public art can also ask the larger questions about what values we hold and what kind of city we want to live in — and it can propose creative, alternative paths to get there.

Urban planners are increasingly seeking ways to bring public art into their planning processes because of its unique ability to create common conversations about our cities and their futures. This is more than simply a trend; it is an effort to consider the ways that artistic practices can help shape public opinion and policy, and ask whether we can go beyond the conventional, top-down consultation process that takes place between citizens and those in power.

While consultation processes sometimes try to incorporate nonmainstream voices, this process still assumes that everyone will speak in the agreed-upon planning and policy vocabulary. But what if artists are able to use their own language to address broader issues where traditional forms of political engagement, city planning and policy development may fall short? Could an exhibition, with a range of interdisciplinary activities, foster this? Could it create new conversations about our cities?

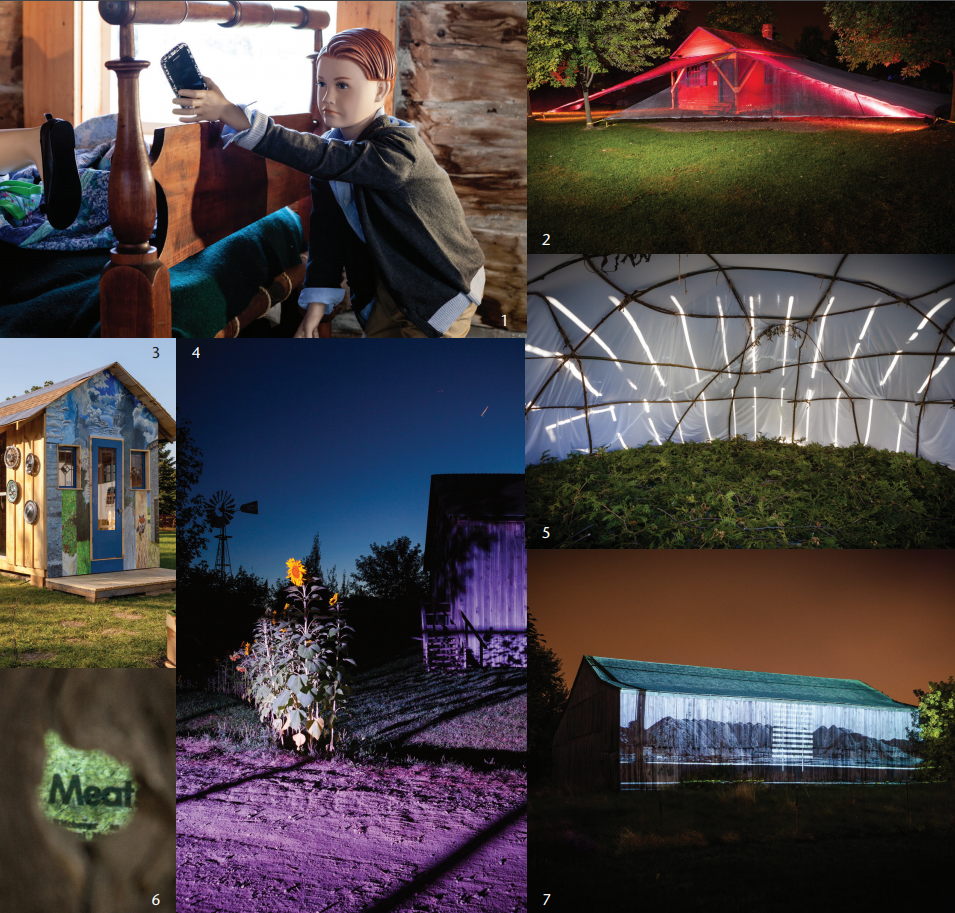

These are some of the questions we sought to answer over three weeks in September and October with a public art intervention called Land|Slide: Possible Futures at the open air heritage village of the Markham Museum in southern Ontario. The museum is located in one of Canada’s most culturally diverse and fastest-growing cities, spreading across one of the most agriculturally rich regions in North America. (Markham is on the edge of Ontario’s massive, 1.8-million-acre Greenbelt, created to preserve farmland and natural spaces within the rapidly growing region around Toronto.) Travelling to the museum from Toronto offers a window into a changing landscape: strip malls to the east, new condo developments popping up directly north, and the growth of subdivisions on class 1 agricultural lands is visible throughout the city.

The vanishing Markham is preserved at the museum, home to nearly 80,000 artifacts from the city’s days as a rural village. The museum’s barns, schoolhouse, blacksmith shop, church and general store are among 30 buildings that date from the 1820s to the 1930s. Land|Slide commissioned 30 national and international artists to reinterpret these artifacts and heritage homes and comment on some of the most pressing tensions we face: the balance between ecology and economy, development and preservation, diversity and history.

There is a growing awareness among planners, urban policy-makers and residents of the importance of arts and culture within cities. Much of the discussion focuses on how a city’s cultural and artistic viability can attract tourists and boost the local economy. Since 2000, the City of Toronto has increased the development of policies, plans and guidelines highlighting the benefits of art and culture for the city’s economic development (for example, Culture Plan for the Creative City, Creative City Planning Framework, Percent for Public Art Program). Smaller cities within the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area (GTHA) are following suit. Markham is one of the first of these to pass a culture plan.

Ontario also has more technical planning tools that can be used to fund and enhance arts and culture. The Ontario Planning Act’s section 37 allows municipalities to extract benefits from developers in return for permitting buildings to exceed height and density restrictions. Those benefits are loosely defined, but have included amenities such as parks, affordable housing units and the protection of heritage sites. Section 37 can also be used to spawn public art and cultural projects: for example, the Artscape Wychwood Barns and Triangle Lofts in Toronto show how section 37 funds have been used to provide floors of space and housing for artists in developments.

But section 37 has its limitations. For one thing, the Act’s requirements are only to provide building costs, not operating funds, which creates real-world limits for small arts organizations. Arts and culture often take a back seat to other community amenities such as parks and affordable housing.

In addition to developing arts and culture policy, city planners and staff have recognized the need to include artists in conversations about our cities. The City of Toronto’s Culture Division recently retained two firms to facilitate a year-long public consultation process called Making Space for Culture, which has engaged artist and cultural groups in a dialogue about needs within their communities, with the goal of long-term investment for sustainable and affordable cultural spaces using section 37 funds.

Making Space for Culture acts as a two-way dialogue, according to Melanie Melnyk, senior planning consultant from R.E. Millward and Associates: the arts and community groups educate the planners on the communities’ needs, and the planners educate the community about section 37 funding. To Melnyk, this is an important exchange, because while “city planning is often seen as policy driven…it’s at its best as a community-led process.”

Samantha Rodin, associate director of the York Region Arts Council, supports this two-way interaction as a way to get to the real concerns of artists. But she argues that the nature of the dialogue also has to change: “Artists often feel they need to speak in business terms and dollars and cents when speaking to politicians and planners, highlighting how their work will produce a return on investment.” She believes that the focus should equally be to articulate the social impact the arts can have within communities.

Jonathan Metzger of the urban planning division of Stockholm’s Royal Institute of Technology is a forceful advocate for bringing artists into the planning process. Metzger thinks that artists are granted artistic licence “to be strange,” while planners are expected to be straightforward problem solvers.

“The unique potential of planner-artist collaborations is based on the artistic license that grants the artist a mandate to set the stage for an estrangement of that which is familiar and taken-for-granted,” Metzger writes, “thus shifting frames of references and creating a radical potential for planning in a way that can be very difficult for planners to achieve on their own.”

It is this very freedom that allows artists to bring fresh perspectives to the decision-making process that shape our public spaces.

The Land|Slide artists transformed the well-preserved but static Markham Museum heritage village, opening it up for contemporary dialogue through surreal, utopian and haunting artworks. The exhibition sometimes blurred the space between past and future using installations, performances and sculptures, 3-D cinema and photography, and cameras that slow the world down and others that project it large. They augmented the past — in often humorous and always creative ways — to suggest interwoven lines of human culture, wildlife, migration and sustainability that must be considered as we plan and develop our future landscapes.

Among the many Land|Slide projects, three examples show how the installations created important conversations centred on Markham’s planning framework:

- Jennie Suddick, Land|Slide artist and former Markham resident, uncovered planning-related themes through storytelling for her project Stomping Ground. She interviewed a number of local residents, asking them to recall their favourite natural spaces within the city. From the interviews, she created an interactive Web-based documentary and a series of handmade trail maps that uncover some of the hidden and past natural spaces within Markham.

- Taiwanese-Canadian artist Angel Chen used the dim sum tradition to create a menu of urban planning options and asked participants to order the city they want to live in. Chen’s Dim Sum City is a playful and performative installation that encouraged people to envision their city and share their ideas with the public.

- Xu Tan, an artist from Shenzhen, China, who has spent months in Markham learning about the area, raised questions about development in Markham and asked residents to reflect on what it has meant to them. The audience, both residents born in Markham and newcomers, discussed their relationship to the city in his installation Echo Wall.

But these installations are part of a much broader research project. Land|Slide is the culmination of two years’ work to involve a diverse collection of stakeholders in a collaborative and interdisciplinary exhibition. It reached out to residents, environmental and food organizations, planners, developers, the City of Markham staff, academics and the arts community, in the process ensuring that Land|Slide would raise important questions and issues within Markham’s planning framework. Among them:

- The Greenprint Sustainability Plan: Partnering with the City of Markham’s Sustainability Office, Land|Slide brought Markham’s innovative Greenprint Sustainability Plan to life through weekly panels and community mapping workshops focused on expanding the concept of sustainability. Through these events we have incorporated issues of the arts, food accessibility and heritage into the sustainability framework. • The Greenbelt Plan: Aimed at protecting farmland and natural spaces, the plan is up for review in 2015, and was referenced in many of the installations as well as within the overall exhibition.

- The Foodbelt Proposal: Land|Slide was inspired by the 2009 Foodbelt Proposal put forward by two Markham city councillors, in which surArtists have something to say about our most pressing tensions: between ecology and economy, development and preservation, diversity and history. rounding land would be secured for agricultural production. The proposal was defeated in 2010 when 7 of 13 councillors voted against it. By focusing installations on food, farming and land use, the exhibition reintroduced many of the themes that sparked the original proposal.

- New priorities: Land|Slide’s focus on sustainability, culture, community, food and farming, diversity and outreach may encourage new priorities to surface within Markham.

- The importance of the arts: Land|Slide intends to inform stakeholders and audience members of the important role the arts can have within planning and policymaking. Exhibitions such as this can foster an appreciation for the arts. An example of this is Marchessault’s past exhibition, the co-curated Leona Drive Project, which helped create North York Arts, the local ward’s new arts council.

The artworks and interdisciplinary events of Land|Slide, from food and farming programming to panels, workshops, artists’ talks and guided tours, all showed how a public conversation can be created around issues of sustainability, culture and community. As we consider what we want our cities to be, we must remember to see them as expressions of our entire culture, and ensure the artistic voice is heard

Photos: Will Pemulis.