Too often, when world attention turns to Canada, it is intermittent and with a narrow lens, rather than a broad focus. That is unfortunate, because in today’s volatile and uncertain global environment, with all countries facing significant challenges, a country’s relative position on a broad range of economic, fiscal, financial, social and institutional factors conveys a more fulsome sense of its current and future capability. It is in that context that this article presents a 2010 global snapshot of Canada, in conjunction with the Policy Options year in review.

Canada has been doing a lot of things right over the last 15 years, notwithstanding our ongoing challenges with weak productivity growth and innovation performance. Canada withstood the financial crisis better than most other countries and, during this time of uncertain global recovery, we have a strong story to share with the rest of world. Our relative global strengths include

- Solid economic fundamentals

- A diversified and sophisticated economy

- Robust resources — both natural resources and human resources

- A sound financial system with strong financial institutions

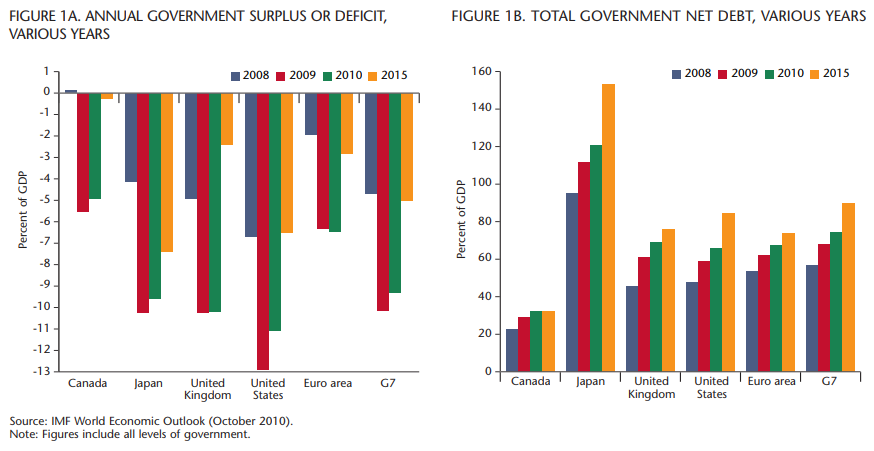

The relatively strong economic and financial performance we have enjoyed has been partly the result of good policy foundations — Canada’s economy was underpinned by prudent public finances. Canada enjoys a solid fiscal position. Our budget deficit as a percent of GDP is low relative to other G7 countries. Net debt as a percent of GDP for Canada in 2010 is projected to be 32 percent of GDP, well below that of the US and other G7 countries (figures 1a-1b).

Looking ahead, the International Monetary Fund expects that our net debt as a share of economy will be less than half that of the US by 2015, and we will be the only G7 approaching fiscal balance.

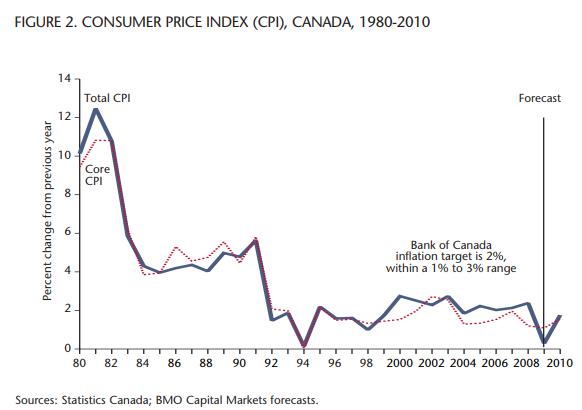

A second element of our strong fundamentals is that Canada has had an effective inflation targeting monetary policy, in place since 1991 (figure 2).

The current target, as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) is 1 to 3 percent, with the Bank of Canada dedicated to keeping inflation at the 2 percent target midpoint. As of August 2010, the CPI annual inflation rate was 1.7 percent. Indeed, Canada has stayed well within its inflation target range since 1992.

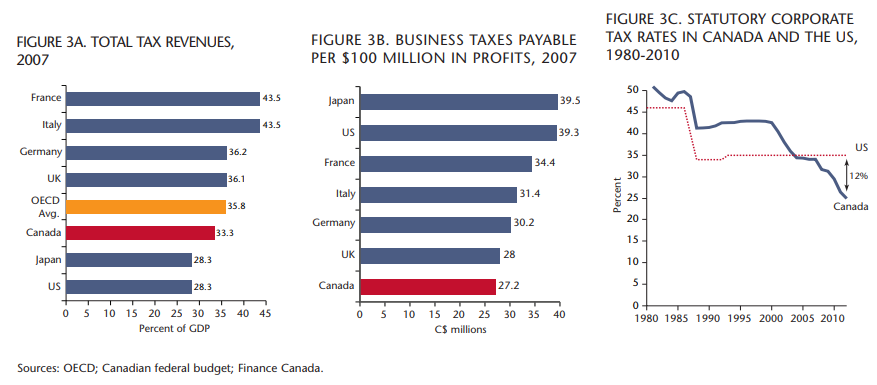

Third, Canadian tax rates, both individual and corporate, are low by G7 standards, and particularly corporate income taxes, to encourage investment in Canada by both Canadians and non-Canadians (figures 3a-3c).

According to a study by KPMG, Canada offers the lowest effective corporate income tax rate in the G7 for manufacturing operations and corporate and IT services. Further, Canada has created a significant corporate income tax advantage over the US since 2000. Presently, Canadian corporate income taxes are 12 percentage points below those of the US, encouraging investment, jobs and growth in Canada.

Canada’s is a diversified and sophisticated economy, quite different from its traditional image. While we may be known as hewers of wood and drawers of water, we are a global power in commodities the world wants and needs, from oil and natural gas to potash and other minerals in the ground.

In the past decade, however, the largest growth has been driven by the service, retail, scientific and technical sectors. For example, Canada is home to the third largest civilian aerospace industry, and it is also recognized as a leader in life science industries such as medical equipment, biotechnology and pharmaceuticals.

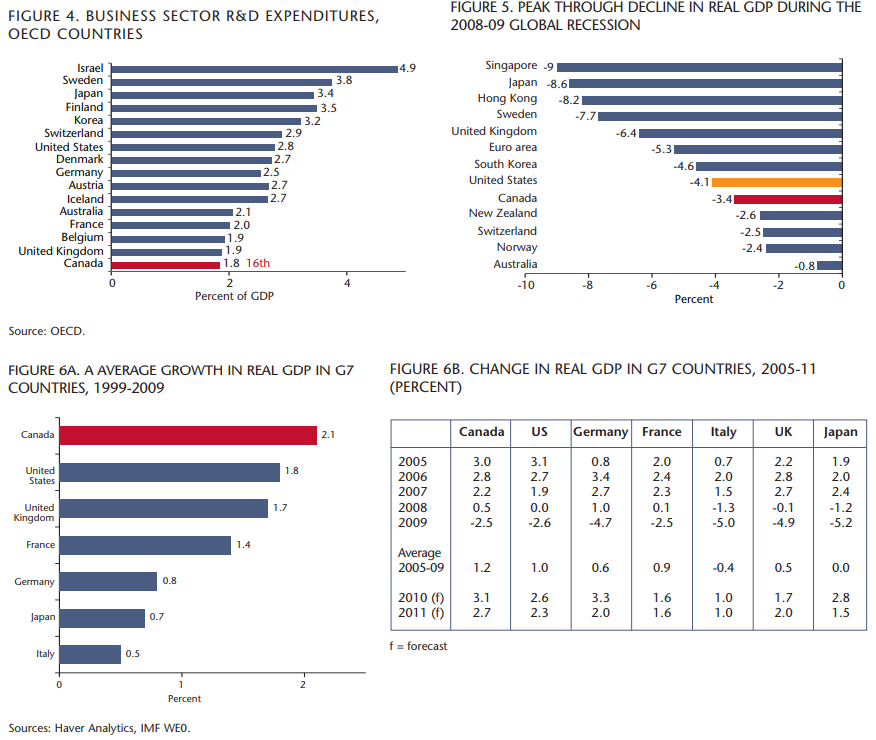

That said, we have an innovation deficit. While our public and university research capabilities are strong, we have poor innovation performance by the business sector (figure 4), and this hurts our productivity growth. Looking ahead, we need to shift all sectors of our economy further along the value-added chain.

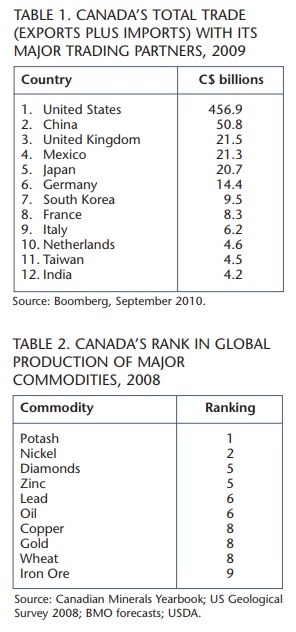

Canada trades with a diverse group of partners (table 1). We are highly integrated with the largest and richest market in the world, the US, through NAFTA and strong bilateral investment linkages.

Canada has historical ties with Europe and emerging trade links with Asia and the Americas. In the future, Canada must look to deepen and broaden its relationships with the rapidly emerging economies in Asia, particularly China and India, as well as with Brazil.

Canada has been blessed with abundant natural resources and, as noted, is a world leader in the production of many key commodities. As world demand for natural resources grows in line with rapid Asian expansion, this clearly benefits Canada.

For example, Canada is the world’s largest potash producer, accounting for 50 percent of the world’s production, with 30 percent alone accounted for by PotashCorp We are the world’s second largest uranium and nickel producer, and a major energy producer with the second largest oil reserves in the world (table 2).

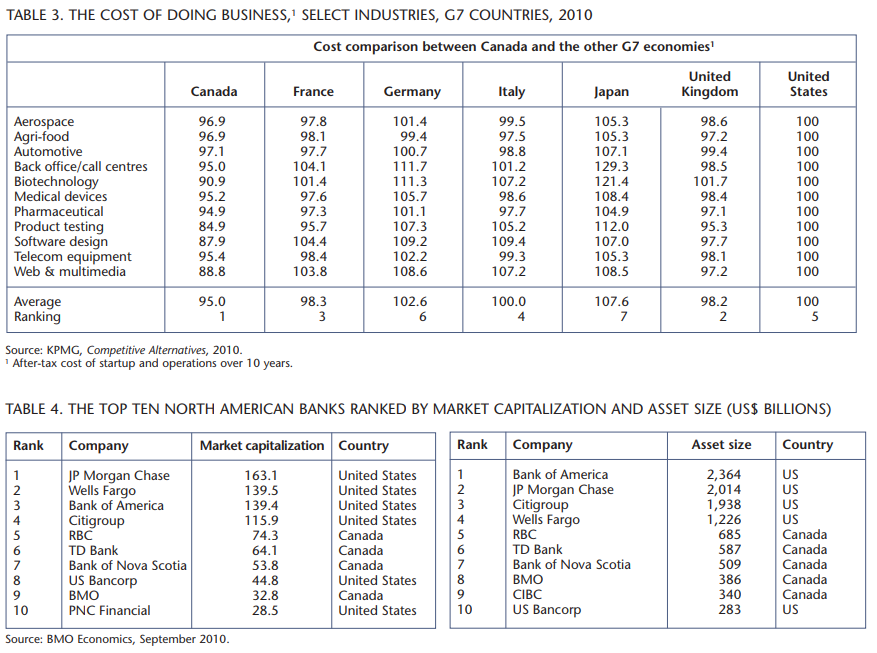

In a recent international study by KPMG, Canada was named the cost leader among the G7 group of countries across a number of key sectors (table 3). Moreover, when 100 global cities were evaluated, Montreal, Vancouver and Toronto were all ranked in the top ten.

Canada’s workforce is educated, skilled and multicultural, with immigrants from well over 115 countries contributing to a vast array of cultural heritages and languages. With the globalization of markets and economies, this diverse, multilingual and multicultural talent base represents a wonderful strategic advantage for Canada and Canadian companies.

For the third consecutive year, the World Economic Forum has ranked Canada as having the soundest financial system in the world, bar none. The IMF has also lauded the Canadian financial system, noting that it has been resilient through the financial crisis and recession thanks to rigorous regulation and prudent bank practices.

Canada was the only G7 nation whose banks did not require a government bailout during the recession; they remained liquid and profitable; and they continued lending.

Since the financial crisis, Canadian banks have grown compared with their American counterparts. Today, four of the major Canadian banks rank among the top ten financial institutions in North America in terms of market capitalization and asset size (table 4).

Canadian banks also have extremely strong tier 1 capital ratios, a key measure of strength and resilience. Again, four Canadian banks are among the top ten major North American banks in terms of capital adequacy, and three Canadian banks are in the top five.

This was a very different recession for Canada compared with those of the 1990s and 1980s. This time, among the G7 countries, Canada had the smallest decline in real GDP during the global recession, faring much better than the US despite the high degree of Canada-US economic linkages (figure 5).

And this relatively robust and resilient performance existed before, during and after the global recession. Canada led the G7 countries in growth over the decade prior to the global recession, and the IMF predicts we will lead G7 growth in the recovery (2010 and 2011) (figures 6a-6b).

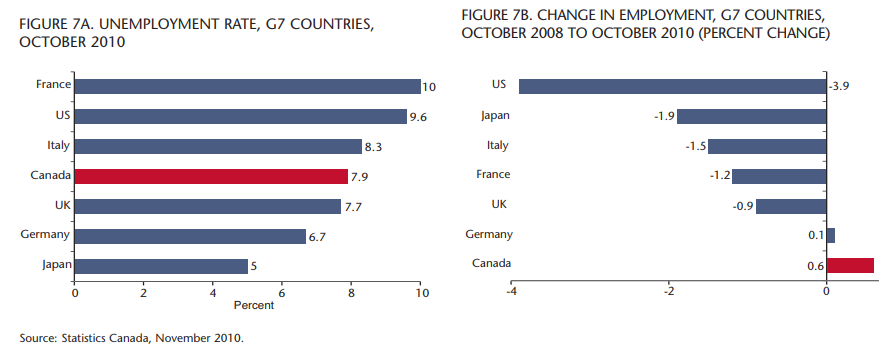

Remarkably, Canada’s labour market has recovered all of the jobs lost during the recession, and then some (figures 7a-7b). This stands in sharp contrast to the US. Moreover, Canada has a much lower unemployment rate than the United States, where the unemployment rate is at a 27-year high.

Canada’s relative strengths are also reflected in the performance of our dollar. Since 2000, Canada has enjoyed an increase in the value of its currency against all its significant trading partners, including a 40 percent appreciation against the US dollar.

Canada is also moving up in the world performance rankings. The IMD annual competitiveness rankings, based on economic performance, government efficiency, business efficiency and infrastructure, placed Canada 7th in the world in 2010. In the latest ranking of countries by corporate governance performance, Canada was ranked 2nd. And, the United Nations’ Human Development index ranks Canada 4th in the world.

It was not luck that enabled Canada to weather the 2008-09 global financial crisis and recession with such resilience. It was solid economic management over more than a decade, a low debt, a diverse economy, and a sound financial system. We were the beneficiaries of a virtuous fiscal cycle, of balancing the books beginning in 1997, and of paying down nearly $100 billion in debt before the Great Recession necessitated the period of cyclical deficits we are currently moving through.

Now, going forward, there is more to do to build on these relative strengths and not rest on them. We need to tackle our productivity and innovation deficits. We need to broaden and deepen our economic ties with key emerging markets. We need to tackle the challenges posed by an aging population. And most importantly, we need to compete to win in a rapidly changing world economy, because we can.

Photo: Shutterstock