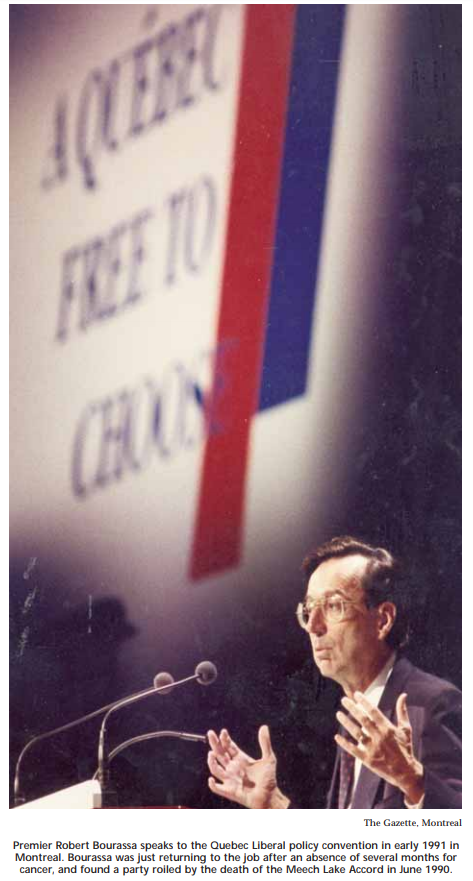

Since 1960, Canada has been governed by prime ministers coming from Quebec for 37 years (Trudeau, Mulroney, Chrétien, Martin) and for 15 years from the rest of Canada (Diefenbaker, Pearson, Clark, Campbell, Turner, Harper). It goes a long way in explaining the importance that the Quebec agenda of constitutional reform and language politics has played on the national scene. Being chosen in the top 5 among Canadian premiers in the last 40 years is the recognition that Quebec Premier Robert Bourassa (1970-76, 1985-94) played a central role in how the national debate was framed.

His vision, which included a primary role for Quebec within the Canadian constitutional family, and his resilience (nearly 15 years in office and four election victories) on both the provincial and national scenes illustrate why Bourassa was the most politically significant Quebec premier of his time and the one who interacted the most with his fellow premiers in Canada.

Jean Lesage (1960-66) is generally acknowledged in Quebec history as the most transformative premier of modern times in Quebec. Lesage followed the autocratic rule of Maurice Duplessis, who was an avid opponent of emerging progressive forces in Quebec and not considered an active player on the Canadian national scene. Back then, Lesage and his party represented much of the progressive thinking in the province, and he quickly engaged with the rest of Canada to explore the possibility of constitutional reforms.

To understand the scope of the Bourassa years, we must refer to the decade preceding his own election and the forces that came to be. The 1960s ushered in a period of profound transformational change and Liberal Jean Lesage and his équipe du tonnerre became the principal vehicle for change. His tenure in office, known as the Quiet Revolution, marked an important shift in Quebec’s traditional power structure.

Under Lesage’s stewardship, the education system began the transformation from a strongly religious dominated sector to a modern, secularized system. Changes were also brought to the health care, economic and energy sectors of the day. Inspired by the slogan of Maître chez nous, the state-owned Hydro Québec nationalized some privately owned energy companies, paving the way for making Quebec an energy powerhouse.

By the time Lesage left office in 1966 (he was defeated by the Union Nationale’s Daniel Johnson, father of future premiers Pierre Marc and Daniel Jr.), his work though highly transformative was still inconclusive in the realm of constitutional reform, social policy, language policy and economic development.

Despite his many progressive reforms, Lesage was unable to quell an emerging sovereignty movement that seemed to capture the imagination of a new generation. While the reforms of the Quiet Revolution remained in place under the more conservative regime of Daniel Johnson and, later, Jean-Jacques Bertrand, it was clear that a more significant rendezvous with history was in the making.

René Lévesque, possibly Lesage’s most popular minister, left the Quebec Liberal Party in 1967, eventually forming Parti Québécois (PQ) the following year. He soon became the principal architect for promoting the separation of Quebec from Canada. Meanwhile, the charismatic Pierre Trudeau of the federal Liberal Party was elected prime minister in June of 1968, arguing for a strong national government to combat the rise of Quebec separatism. A constitutional confrontation between federalist and sovereignist forces in Quebec was about to become a growing force on the national scene.

Robert Bourassa, a youthful MNA elected in 1966 with strong economic credentials, gradually emerged as the rightful heir to Jean Lesage. With the popular Lévesque and his PQ gaining strength, it seemed Quebec was also looking to a new generation of leadership within the established Quebec Liberal Party. It soon became clear that Bourassa’s vision was not limited to pushing and completing what Lesage’s Quiet Revolution had begun, but also to making economic development the central part of his mission in public life. However, he quickly became aware that he needed to address the constitutional issue from a Quebec federalist perspective should he form the government.

In 1970, the Harvard and Oxford educated economist became leader of the Quebec Liberals and was elected Quebec’s youngest premier on April 1970, at age 36. Lévesque and Trudeau now had company when it came to discussing the future of Quebec within Canada and fighting for the hearts and minds of Quebecers.

His vision, which included a primary role for Quebec within the Canadian constitutional family, and his resilience (nearly 15 years in office and four election victories) on both the provincial and national scenes illustrate why Bourassa was the most politically significant Quebec premier of his time and the one who interacted the most with his fellow premiers in Canada.

Unlike Lesage, who had battled and defeated an existing order, Bourassa took office at a time when a new political and social order was already taking shape. The PQ, reform minded with a social democratic and prosovereignty outlook, became the major opposition party. The union movement, empowered by years of combating the conservative and repressive government of Maurice Duplessis and emboldened by new labour legislation from the Lesage years, became a force to be reckoned with when it came to public service employee negotiations. Finally, a political terrorist group the FLQ (Front de Libération du Québec) burst into the forefront with the kidnapping of British diplomat James Cross in Montreal, and the murder of one of Bourassa’s key political lieutenants, Labour Minister Pierre Laporte a few days later.

This period of turmoil was taking place when the freshly elected Bourassa’s government was embarking on a major reform to the provision of health care services by bringing in medicare over the objections of Quebec doctors. The latter had chosen to voice their opposition with a province-wide strike.

Meanwhile, the FLQ crisis resulted in the application of the War Measures Act, at the behest of Premier Bourassa. It was an immediate test for the new premier and his leadership skills. In this early period of turbulence and uncertainty, he proved to be a cool and steady leader in the face of adversity and change. It was his trademark in the years to come.

Overall, Bourassa’s 15 years in office show a combination of his vision and his resilience. There were profound and new economic forces at work where the Quebec economy gradually moved from a more traditional manufacturing model in the 1970s to a high-tech, knowledge-based economy, and where Quebec in the 1980s and 1990s, under Bourassa’s stewardship, was able to become a major proponent of free trade with the US in 1987-88 and, later, with Mexico in the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1992-93.

Bourassa’s most important contribution to the economic future of Quebec, however, was the development of Quebec’s energy potential.

In 1971, he launched the most ambitious project in Quebec history — the development of the James Bay Hydroelectric Project. I recently visited these installations with some American friends from my days as Quebec’s delegate general in New York. Visiting the Robert-Bourassa Power Station Visiting Centre provides concrete evidence of Quebec’s enormous renewable energy capacity and potential. It has vindicated Bourassa’s stand in favour of hydroelectric power over the nuclear energy option, which was supported back in the early 1970s by the opposition PQ.

Quebec society, which today has North America’s lowest carbon footprint, has its electricity generated by over 95 percent from renewable sources. By the time Bourassa left office in 1994, Quebec had become a leader in renewable energy, biotechnology and aerospace. Successive premiers have acknowledged his contribution and some, such as current Premier Jean Charest, have expressly built on his accomplishments.

Outside of medicare, working to transform the Quebec economy, building the James Bay project and free trade advocacy, Bourassa also made many other important structural reforms to civil society that have passed the test of time and continue to be a cornerstone of today’s Quebec society. These include making French the official language of Quebec, while ensuring respect for English-speaking institution and minority rights, establishing Quebec’s first immigration and environment ministries, adopting a charter of rights and freedoms, setting up legal aid, negotiating a quasi-constitutional agreement with the Quebec Cree nation to develop the James Bay Project, establishing the Council on the Status of Women, and harmonizing both the federal and the provincial tax system to make the Quebec economy more competitive internationally.

Finally, his government concluded a quasi-constitutional agreement in 1991 (administrative arrangement needing the assent of both the Quebec and Canadian governments to change or abrogate it) on immigration, giving Quebec additional powers and funds for selection and integration of immigrants. This agreement is now considered essential to Quebec’s demographic future.

Lesage may have started the process to modernize Quebec society by changing its institutions, but Bourassa went further by transforming its economy, tapping into its energy potential and redistributing the wealth created through important social programs. In so doing, he made Quebec stronger for future generations. Lesage would have approved.

Bourassa was, above all, a strong believer in federalism — a federalist vision based on economic imperatives and political realities. Unlike some Quebec federalists serving at the federal level, his federalism was not of the emotional kind and in so being, it did not generate the kind of passion that his counterparts in Ottawa would have wished. It did not prevent him from engaging in constitutional reform and being an enduring figure in the process. No other premier has engaged in as many constitutional reform exercises as Bourassa.

While his cherished goal of constitutional reform proved to be elusive, it was not from a lack of trying. He was a key player at the Victoria conference 1971, the Meech Lake Accord (1987-1990) and the Charlottetown Accord (1992). He was also actively involved campaigning for the No side in both the 1980 and 1995 referendums on sovereignty. It is accurate to conclude that Bourassa was a persistent and determined opponent to those promoting Québec sovereignty.

To fully appreciate Bourassa’s approach to federalism and constitutional reform, however, it is important to understand how Quebecers see Canada and how they see themselves and their leaders in the process. While Bourassa was a federalist, he was expected to be a defender of Quebec’s interests at the constitutional table. His positions were rooted in Quebec’s political culture.

The French language, culture and historic character have conditioned for centuries how Quebecers approach their governance. For many Quebec historians and political theorists, the British Conquest of 1760 marked the beginning of the quest for the survival of a people under new rulers. The Quebec Act of 1774, a British act, recognized the characteristics for survival (religion, language, territorial management, the civil code) that fostered the Quebec identity and made this identity a significant part of its political culture. Subsequent events ranging from the Constitutional Act of 1791, to the Rebellions of 1837-38, to the Durham Report, to the Union Act of 1841, and to the achievement of responsible government (1849) only reinforced the notion of la survivance and Quebec identity. Any changes in governance had to consider this reality.

To most Quebecers, Confederation is a compact between two founding nations — French and English. Canada is seen as a creation by four provinces (New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Quebec and Ontario) and the federal formula is understood as a compromise. Every Quebec premier is conditioned by this history and must be seen to protect and defend Quebec’s jurisdictions and interests as a priority. This explains why Quebecers consider their provincial government as the one closest to them and consider the special stewardship of its premier as essential to its very survival.

With Quebec being the only jurisdiction with a French majority (82 percent) in North America, no Quebec premier can expect to be elected without a profound understanding and defence of Quebec’s identity. The rise of the PQ party under the popular René Lévesque only made this reality more acute to Bourassa and his government. Any perception of weakening Quebec’s powers or interests can serve to reinforce the prosovereignty forces, which remained his principal opposition throughout Bourassa’s tenure. Any failure, as we saw later with the Meech Lake Accord, could bring the country to the brink of breaking up.

It is within this political dynamic that Bourassa had to operate at the constitutional table. His refusal to ratify the Victoria Charter (much to Prime Minister Trudeau’s chagrin) had a lot more to do with forces within Quebec, who felt threatened by the agreement, than his own objections. Bourassa chose then to say no, though in later years, he expressed regret about that course of action and regarded it as a mistake.

The 1980 referendum results in Quebec in favour of federalism presented the opportunity to pursue constitutional peace between Quebec and the Rest of Canada (ROC). After all, 59.6 percent of Quebecers rejected the PQ formula of sovereignty-association and responded to Prime Minister Trudeau’s appeal for real constitutional change. The subsequent events, which led to the repatriation of the Canadian Constitution without the Quebec government’s formal consent, failed to solve the problem or end the debate, which in that sense continues to this day.

True, Lévesque was the Quebec premier and could hardly become a new father of Confederation along with Trudeau, but Quebec’s nonsignature served to divide Quebec-based federalist forces. Bourassa returned to power in 1985 in this context. But with a new premier and a new prime minister (Brian Mulroney was elected prime minister in September 1984), a new opportunity for constitutional peace eventually surfaced.

Soon after Bourassa came back to power in December 1985, he accepted Prime Minister Mulroney’s overture for another constitutional round. They knew each other well and were close friends. Optimism was in the air. Bourassa laid out some key conditions, most notably the recognition of Quebec as a distinct society and the return of the Quebec veto on future constitutional change (a veto bargained away by René Lévesque and the so-called Gang of Eight, who opposed Trudeau’s constitutional package of 1982). The result was the Meech Lake Accord of 1987, with ratification to be completed by June 1990. The length of the process, however, proved to be the undoing of the Accord.

By 1990, the mood in Canada had changed and some provinces, who were early backers, had new premiers who now opposed the original Accord (Frank McKenna in New Brunswick, Clyde Wells in Newfoundland). The opposition by former prime minister Trudeau only reinforced the resistance to the Meech Lake Accord. In June 1990, after a valiant attempt to save it, the revised Meech Lake Accord failed to be ratified. Bourassa and the ROC now faced a real constitutional crisis, one that could lead to the separation of Québec from Canada.

Following the failure of the Meech Lake Accord, support for sovereignty rose to over 65 percent support. Here, notwithstanding the strong approval ratings for sovereignty and the expressed hope by some that Bourassa would achieve it, he chose instead to engage in another risky constitutional exercise that culminated in the Charlottetown Accord of 1992. While Bourassa made some important gains for Quebec in the agreement, the 1992 constitutional deal did not generate much enthusiasm across Canada. A national referendum, held to ratify the Accord, failed. Even Quebec voters rejected Bourassa’s endorsement of the Accord by a 55-45 margin.

The constitutional question remains unsolved to this day but Bourassa, by his willingness to engage in two more constitutional rounds and not pursue sovereignty, played a role in preventing the breakup of Canada. Through his entire political life, Bourassa never wavered in his belief that Quebec’s best course was to remain a part of a federal Canada.

All who worked with him would spontaneously speak of his gracefulness, his generosity, his humility and his genuine kindness. His disarming sense of humour in small groups and his unwavering belief in public service always made him an instant hit with young people who remained throughout his entire life his most cherished constituency, irrespective of their political allegiances.

Just recently, a biography of Robert Bourassa by renowned Quebec author Georges-Hébert Germain was published, sparking once again a look at the Bourassa years and his legacy.

What this biography shows has a lot to do with the personality and the character of this complex man. All who worked with him would spontaneously speak of his gracefulness, his generosity, his humility and his genuine kindness. His disarming sense of humour in small groups and his unwavering belief in public service always made him an instant hit with young people, who remained throughout his entire life his most cherished constituency, irrespective of their political allegiances.

What was most appealing, however, was his approach to politics and the intensity of political debate. He was a visionary and inspired a generation of followers, who became engaged in defending and promoting Quebec’s interests. He never personalized differences with his political opponents. He could disagree without being disagreeable. His civility and his respect for the achievements of previous governments as a basis to build on have also earned him much respect and affection beyond the partisan divide. And finally, his primary purpose for engaging in political life was to build for future generations a society where economic development and prosperity would contribute to advancing social justice for all citizens.

Germain recounts Bourassa’s years in the political desert after he lost power to the PQ in 1976 and resigned as leader of the Quebec Liberals. He never abandoned his goal of returning to power, even if there was “only a 1 percent chance of making it happen.” He eventually became the only leader in Canadian history to regain the leadership of his party after losing it. And this says much about the resilience of the man.

Bourassa never gave up. Even in his final days, according to his wife, he still clung to the hope that he could beat his cancer. Despite the disappointments, he was hopeful about Canada, the federal system and the opportunities to grow together. Clearly, his accomplishments were many, his failures were few. After all these years, he remains a model for many who still believe in the nobility of public service and the belief in the potential of one’s fellow citizens.

Today, Quebec’s Premier Jean Charest often refers to Bourassa’s vision, his character and how he is an inspiration to him every day. He often reminds us about how Bourassa never gave up in the face of adversity.

When one examines Premier Charest’s emphasis on finding new economic markets, advocating for a free trade agreement between Canada and the European Union, passing legislation on pay equity, developing the Quebec north with his Plan Nord and promoting Quebec’s leadership in the Canadian federation with the creation of the Council of the Federation, one can see that the Bourassa model is alive and well.

Robert Bourassa won four out of five elections as premier (in two of them he had 50 percent-plus majorities). His times were formative, transformative, sometimes turbulent, but always challenging. His steadiness, his integrity and his unwavering engagement to making Quebec stronger economically, ensuring greater social justice for its citizens and fostering better relations with the rest of Canada best summarize his years in office.

Photo: meunierd / Shutterstock