Economists study how markets, consumers and businesses behave, but they rarely turn the focus inward to study their own behaviour. We did. And our research reveals that economists at Canadian universities are collectively losing interest in the country’s economy and its economic policy issues.

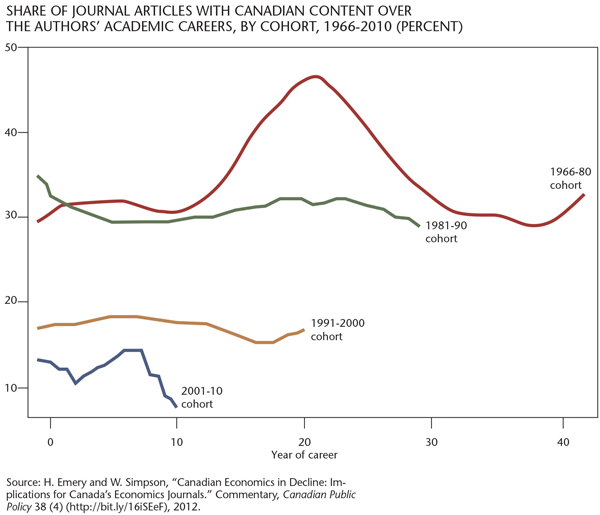

The figure shows a continual drop in the share of academic publications from Canadian economics departments that contain Canadian content. (The full results, available at: https://bit.ly/16iSEeF, are based on Emery and Simpson’s analysis of over 3,000 articles by 250 Canadian economics professors.) This trend has been under way for several decades and is particularly pronounced among the country’s best and brightest: those in the top 10 departments, who now do far less work on Canadian issues than they did decades ago.

We think this decline matters. The Canadian economics profession is falling dangerously out of balance. Indeed, if the academic part of the economics profession continues down its current path, it risks becoming irrelevant to Canadian taxpayers, policy-makers and students.

§§§

So what’s behind these troubling trends? One likely explanation lies in the changing recruitment and retention practices within our universities. In the 1990s, immigration laws that had previously given preferential treatment to Canadian academics were relaxed to allow departments to better compete for international talent. Not surprisingly, the increasing prevalence of academics who work in Canada but have studied elsewhere means the pool of academics inclined to study and teach Canadian issues is diminishing.

Another part of the story is the structure of tenure, promotion and merit pay requirements, particularly in the larger, more research-intensive economics departments. Higher expectations to publish may dissuade scholars from studying Canadian issues because it is harder to publish this work in the best journals outside of Canada, which is where scholarly reputations are made (thereby influencing pay and academic rankings).

This tendency is reinforced by changes in how the government funds academic research in Canada, with an increased concentration of resources in top-tier university departments. These are the very departments where the pressure to publish in international journals is most intense and where, our study shows, there is far less Canadian-focused work being conducted.

Finally, Canadian studies may also be a victim of an excessive emphasis on abstract economic theory, in line with the “mathematization of the profession” (or what some call “physics envy”). This type of research is again potentially more attractive to international journals, but often less useful to nonspecialists and policy-makers seeking to understand our economy and how best to guide it.

§§§

Some people might argue that the de-Canadianization of university economics departments doesn’t matter. The work is still going on, they might point out. It’s just happening elsewhere: in public policy schools, business schools, health programs and even think tanks (which were not in our study), all of which may be picking up the slack.

Others might even argue that this development is a good thing. After all, Canadian economics departments are receiving high global rankings, which benefit our universities, helping them attract high-quality faculty and graduate students.

But we see several reasons for concern. First is the question of whether Canadian taxpayers are getting reasonable social value for their money. Canadians fund a significant share of the work in academic departments. They reasonably might expect academic economists to focus on concrete policy problems facing those who pay their salaries.

The second worry is that policy-makers seeking evidence to help them make decisions are less likely to turn to Canadian academic economists. Even if there are other sources of evidence, this irrelevancy to the domestic debate should be cause for soul-searching within the profession.

Finally, we worry about the effect on students. The profession-wide disengagement from Canadian issues risks failing a generation of students in Canada who seek knowledge of their economy and the challenges it faces. It means they have less exposure to their own economic institutions and history. By depressing the number of graduates versed in these areas, we risk weakening the capacity of future researchers, policy-makers and informed citizens to engage with Canadian economic issues.

§§§

What, then, can be done to remedy the situation? While there are no quick fixes, we propose three steps to restoring some Canadian focus to the profession.

First, government research funds should be spread more equitably to reach those working on Canadian issues. The way in which governments fund research has an enormous influence on who studies what, and even modest government interventions can help shift the direction of research. A good example is the Metropolis project, funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, which encouraged applied and empirical research on immigrant integration and attracted significant interest from Canadian academic economists within and outside of the top departments (and even some publications in top journals). More should be done along these lines in other areas of interest to Canadian economic and social policy.

Second, academics need more and better data. It is hard to stimulate applied research when data are poor or access to them is limited. Statistics Canada is trying to move in this direction. But recent funding cuts, the loss of important surveys and the dismantling of the long-form census are likely to exacerbate the problem. More public resources are needed to fund data collection and improve access.

Finally, we need a psychological change within the profession. Canadian academic economists must ask themselves how they can best support their key stakeholders. The current incentive structure serves some faculty very well, but it is not as healthy for taxpayers, students and policy-makers. It’s time to look inward and admit we have a problem.

This article is based on “Canadian Economics in Decline: Implications for Canada’s Economics Journals” (Canadian Public Policy, volume 38, number 4, 2012), by Emery and Simpson.