At his October 17 pre-budget meeting with economists from the big banks and think-tanks, Finance Minister Paul Martin was told that his fiscal options are limited as the economy slips into recession. The views he heard were based on a deep-rooted fiscal orthodoxy that has gained many adherents among Canadian business economists and forecasters, the majority of whom believe that government deficits should be shunned like the plague. Unfortunately, this is exactly the wrong advice for a time like the present when decisive action is needed to combat a recession. Economists, like generals, are always ready to fight the last war, which in this case was the gloriously successful war against the deficit.

If Canada is going to do what is necessary to support the United States in combating global terrorism following the destruction of New York’s World Trade Center, the government must rethink its strategy of balanced budgets and prepare to run up some deficits. There are two reasons for this. First, the economic shock waves produced by the tragedy are triggering a recession that will automatically reduce the planned budget surplus. Second, new and costly policy initiatives will be required to improve defence and security and to stimulate the weakening economy.

The Sept. 11 terrorist attack on the United States was also an assault on the world economy. It temporarily shut down air transportation and a large part of the financial sector. The uncertainty and insecurity it created drove the stock market down and severely depressed consumer and investor confidence. Travel and hotels are only the two sectors where spending has been most curtailed. With consumers having less financial wealth and more worries, spending will be hard hit across the board. Hundreds of thousands of workers have already been laid off. The U.S. economy, which was stumbling along before the attack, was pushed over the brink into a recession.

The Canadian economy also faces a recession, as the Governor of the Bank of Canada acknowledged in a recent speech. Jittery consumers and investors are pulling back here too. The Conference Board reported that business confidence plummeted to its lowest level in ten years after Sept. 11. And exports to the United States will be hurt by the U.S. slump and by the security-related bottlenecks at the border, which are playing havoc with normal trade flows.

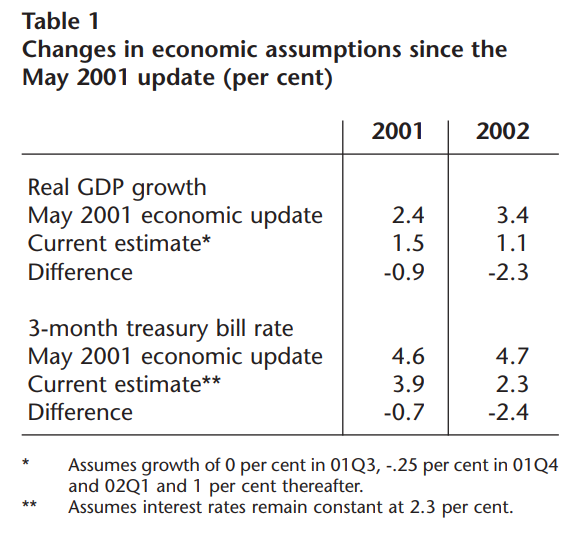

The pre-Sept. 11 slowdown has been transformed by the shock and its after-effects into an actual decline in output that will probably last the two quarters required to qualify as a technical recession. Table 1 compares GDP growth in such a recession scenario with that assumed by Paul Martin in his May 2001 Economic Update (which is available of the Department of Finance website). It shows that real GDP growth would be 0.9 percentage points lower than predicted this year and 2.3 percentage points lower than predicted next year.

The Federal Reserve Board and the Bank of Canada acted swiftly and appropriately in the first few days after Sept. 11 to provide the financial system with enough liquidity to prevent a financial collapse, and they both lowered short-term interest rates by 50 basis points before the stock markets reopened on Sept. 17. The Fed lowered rates by another 50 basis points following its Oct. 2 meeting and the Bank followed suit three weeks later, cutting Canadian rates by a surprise 75 basis points. After the U.S. national accounts data revealed that real GDP had decreased in the third quarter by 0.4 per cent, over 400,000 jobs had been lost in October, and the unemployment rate had risen to 5.4 per cent, the Fed lowered interest rates by another 50 basis points, the tenth time this year, taking the federal funds rate down to a 42year low of two per cent.

This monetary easing provides needed support to the North American economy. But by itself, it is not likely to be enough. When interest rates are low and confidence is weak, trying to stimulate the economy through monetary policy alone is often compared by economists to pushing on a string. There are several reasons why this is likely to be so. Lower interest rates mean lower disposable income for some households. Consumers, worried about losing their jobs, are naturally reluctant to reach for their wallets even if credit is cheap. Businesses facing excess capacity and falling demand are understandably unwilling to borrow money to finance new investments. And even in normal circumstances, monetary policy is generally agreed to work with long and variable lags of much more than six months. This means that monetary policy alone cannot be counted on to turn an economy sinking deeper into a recession around very quickly. Fiscal stimulus is needed to help with the job.

The need for fiscal stimulus was recognized right away in the United States. Immediately after the Sept. 11 attack, Congress unanimously enacted a $40 billion emergency recovery plan, and provided $15 billion in emergency aid to the airlines. On Oct. 3 President Bush proposed an additional $60 to $75 billion stimulus package of tax cuts and new spending to revive the economy.

The Republican-controlled House approved an even larger $100-billion economic stimulus plan on Oct. 24, but the Democratic-controlled Senate is likely to significantly change the package now that the early post-Sept. 11 spirit of bipartisanship has disappeared. The total amount of all the fiscal measures taken so far add up to $115 billion to $155 billion dollars, which would be greater than the $100 million or one per cent of gross domestic product advocated by Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan in his appearance before the Senate Finance Committee on Sept. 25.

At the time of writing, the composition of the fiscal stimulus package in the United States, which is designed to boost consumption and investment and support laid off workers, is still up for grabs. Possible components include: personal tax rebates; the acceleration of previously announced tax cuts; corporate tax reductions; investment tax credits; faster investment write-offs; and extending unemployment insurance benefits. Yet to be revealed is the additional military spending necessary to wage the war against terrorism.

The U.S. budget is clearly headed back into deficit. This is something that would have been unbelievable just over two months ago, before the world changed. In introducing his stimulus package, President Bush explained that deficit spending was appropriate in three circumstances: a national emergency, a recession, and a war, and that we now have all three.

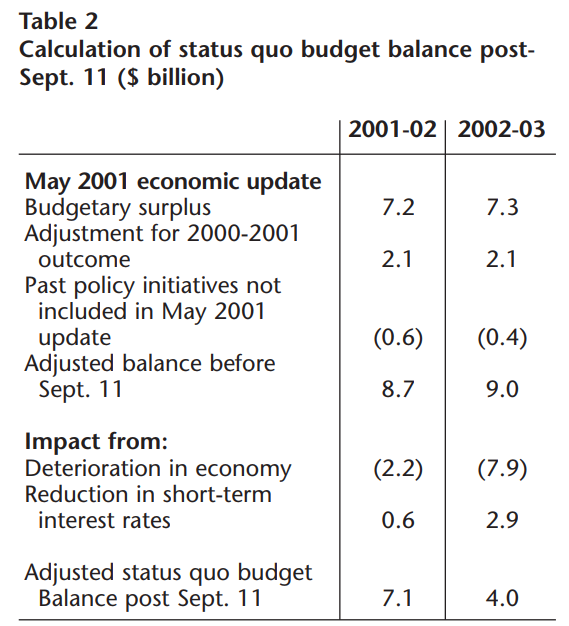

A necessary starting point for commenting on the Canadian government’s post-Sept. 11 fiscal strategy is to develop an estimate of its status quo fiscal position. Before updating the government’s latest fiscal projection released last May to reflect the changed post-Sept. 11 economic assumptions, it is necessary to adjust the projected budget surplus to take into account both the higher than anticipated surplus in the 2000-2001 fiscal year that ended March 31 as well as policy initiatives announced since the May update. Doing so raises the projected surplus from $7.2 billion to $8.7 billion in 20012002 and from $7.3 billion to $9 billion in 2002-2003 as Table 2 shows.

The effects of lower interest rates and slower economic growth, which also have to be factored in, are shown on Table 2. These calculations are done using the rules of thumb presented in the May update (see Table 4, Annex 2 of that document). These rules suggest that a one-percentage-point cut in the growth rate of real GDP would erode the first-year balance by $2.4 billion and the second-year balance by $2.6 billion and that a 100-basis-point cut in interest rates would cause a $0.8 billion improvement in the budget balance in the first year and a $1.4 billion improvement in the second. The assumed deterioration in the economy is estimated to reduce the surplus by $1.6 billion in 2001-2002 and by $5 billion in 2002-2003, leaving the government with a budgetary surplus of $7.1 billion in 2001-2002 and $4 billion in 2002-2003. Apparently, the economic fallout of Sept. 11 is not by itself enough to push the Canadian government into deficit.

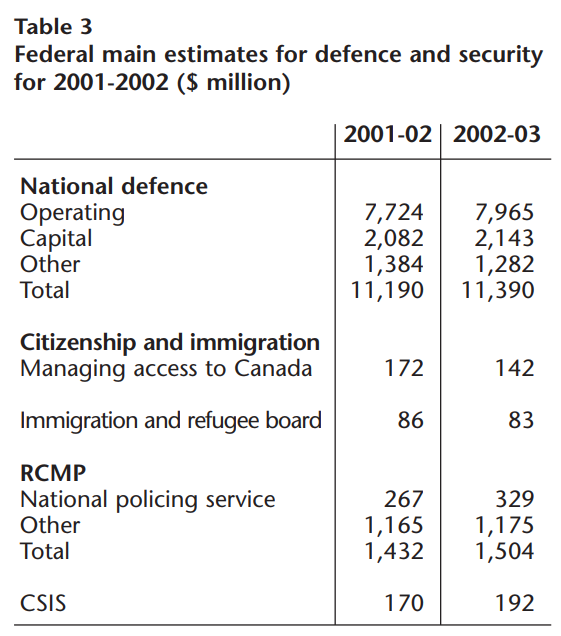

While the government would still have a surplus prior to taking any policy initiatives to fight terrorism and bolster the economy, the surplus would be quickly transformed into a deficit by decisive action of the magnitude that is both required by the gravity of the circumstances and expected by the Americans. Table 3 shows what we currently spend on defence and security, which now looks woefully inadequate.

The biggest increase in spending is likely to be required on defence. As a result of successive budget cuts, the Canadian Forces now number only 53,000 already overextended troops and not enough CF-18s for both “homeland security” and contributions to attacks on terrorist bases. To increase the number of troops significantly and provide them with better equipment would probably require at least $3 billion in the first full year—an increase of more than a quarter. The RCMP and CSIS are also likely to be called on both to provide better intelligence and to devote more efforts to countering terrorism in partnership with the FBI and the CIA. Four hundred million dollars per year would be enough to provide a significant increase in their combined budgets for a full year. Since Sept. 11, the government has already announced $280 million more in spending for increased border and airport security.

For its part, the Department of Citizenship and Immigration will have to put in place a more effective system for screening immigrants, refugees and visitors in order to identify potential terrorists and to make sure would-be entrants are dealt with appropriately and expeditiously. The leisurely timetable currently set out for implementing the “Global Case Management System” that will provide the Department’s front-line workers with the tools and information they need to do their job—the current goal is to finish by 2004-2005—needs to be accelerated. Again, $400 million per year would be a substantial increase in the resources at the Department’s disposal for “Managing Access to Canada” and financing the Immigration and Refugee Board. These funds could also be used to implement some of the suggestions emerging from the “Border Vision” project, an effort to control illegal immigration, which the Department has been jointly pursuing with the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service.

The federal government will have to do whatever it takes to assure the United States that terrorists like Ahmed Ressam or Nabil al-Marabh no longer will be entering Canada from abroad and that any of their associates who already are here will be rounded up and either put in jail or deported. Failing this, a continuation of the border delays we have recently witnessed as the Americans scrutinize everything and everyone crossing their border could seriously damage the Canadian economy. The automobile industry, with its reliance on just-in-time inventory management, has been the first major casualty of the border bottleneck, but others will follow. The quicker we can get back to normalcy at our border with the trading partner that takes most of our exports the better.

Canadian airlines are also going to require support. The cost of being grounded immediately following the terrorist attack is not a normal business risk that they should be expected to incur. Nor should they be expected to bear the increased cost of security that will be necessary to protect passengers and those on the ground from terrorists. This is a public good that government should be required. To provide to prosper, a modern industrialized economy requires a financially sound airline industry. The United States has recognized this with its package of $15 billion in aid for the airlines. Canada will have to do something similar. A rough estimate of the cost is $1.5 billion. The $150 million in aid that the government has already announced for Air Canada and the $75 million loan guarantee for Canada 3000 should be regarded as only a first installment.

The government may also have to contribute another $200 million a year for airport security. For reference, the federal government spent around $700 million in 1990-1991 to run Canada’s airports before it started to transfer them to Local Airport Authorities. LAAs cannot be expected to bear the costs of increased security during a war on terrorism.

A weakening economy will automatically push the federal budget towards deficit. But to stimulate the economy the federal government will need to cut taxes and raise spending, actually creating a deficit, as being done in the United States. A fiscal package big enough to give a significant kick to our $1 trillion dollar economy would be $10 billion, or one per cent of GDP. In addition to the new spending on defence and security, which will be necessary to do our part in the war on terrorism here as well as overseas and which will cost about $4 billion on a full year basis, the fiscal stimulus package needs to include about $6 billion in other spending increases and tax cuts.

The spending increases in the package could be on infrastructure investments, which are traditional counter-cyclical instruments. The tax cuts could include personal income tax cuts where, for example, a one-percentage-point reduction in the rate would cost around $3.5 billion. If the reduction were made retroactive to the current tax year, tax rebate checks could be sent out early in the new year, in time to bolster consumer spending when it will be needed most. A reduction in Employment Insurance premiums is another effective way to increase the purchasing power of low- and middle-income Canadians and to encourage employers to hire more workers. Corporate tax cuts would also be useful to spur investment. This could be accomplished by accelerating the already announced reduction in the federal corporate income tax rate, which is scheduled to drop from 28 per cent in 2000 to 21 per cent in 2004, and is estimated to reduce revenue by over $4 billion. A particular advantage of accelerating the corporate rate cut is that it would not permanently increase the deficit.

If all of the possible initiatives discussed here were taken (see Table 4), the adjusted budget balance would fall by $6.1 billion to a small surplus of $1 billion in 2001-2002, and by $10 billion to a deficit of $6 billion in 20022003. This would be the first budgetary deficit the government has run since 1996-1997. But not to worry: with a deficit that size the debt-to-GDP ratio, which is the most common measure of the debt burden, would continue to fall. Assuming real growth of around 1.25 per cent and inflation of around two per cent, the deficit would have to exceed $18 billion for the debt-to-GDP ratio to rise. This is much greater than the small $6 billion deficit that would likely be produced by the recession and a $10 billion stimulus package.

We need to change our way of thinking and to recognize that a federal budget deficit would not be bad thing in Canada in the current circumstances. Even though large deficits were bad policy in the past when the economy was strong and inflation was on the rise, a moderate deficit would be appropriate now that the economy is slipping into a recession and inflation is non-existent. Hopefully, Keynesianism is not dead, but only recuperating from a bad case of misuse.

Since being elected in 1993, the current government has followed a prudent fiscal policy that first eliminated the deficit and then paid down some debt, bringing the federal debt burden down from a peak of 71 per cent of GDP in 1995-1996 to below 52 per cent at the end of last year. This is much more in line with the economy’s servicing capacity. It has put the government back in a position where it can afford temporarily to run a deficit.

The whole point of the government’s deficit reduction strategy was to restore its fiscal flexibility so that it could take action when needed. Now is clearly the time for action given the gravity of the threat terrorism poses to the security and prosperity of the Canadian economy. Only when the recovery is solidly underway should the government again take steps to eliminate the deficit.

Exactly the wrong thing to do in the current circumstances would be to reduce spending to prevent a deficit from emerging. Heeding calls for fiscal orthodoxy now would just make the recession longer and worse than need be.

Similarly, the federal government cannot rely on provincial governments to take the fiscal action necessary to counter the recessionary forces building up in the economy. All of the provinces except PEI and Newfoundland are bound by balanced-budget legislation that severely restricts their ability to undertake deficit spending. While Quebec has introduced a $3 billion fiscal stimulus package, other provinces are more likely to introduce cost-cutting and tax hikes in their upcoming budgets in order to prevent their deficits from ballooning. And that is how it should be. The federal government is the level of government that is, and should be, responsible for stabilization policy.

In his upcoming budget, Finance Minister Paul Martin needs to do more than just account for the increased spending required for defence and security. He needs to provide the deficit-increasing fiscal stimulus required to turn the economy around and stem the anticipated increase in unemployment. Now is the time to push hard on the fiscal accelerator and not just to coast.

Photo: Shutterstock