What do Dalhousie, N.B., Ponass Lake, Sask., and Rainbow Lake, Alta., have in common? According to our just-released index of economic disparity, they are all among the places with the highest disparity relative to other communities in Canada.

What this means depends partly on how you choose to interpret the numbers. Indices are composite indicators that can provide a useful snapshot of complex phenomena. In this case, we designed the index to capture four elements: population trends, labour force outcomes, working age share of population, and industrial diversity.

This does not mean that they are dying towns unworthy of investment, but rather that they face specific population, employment and economic challenges.

Whether these are the correct indicators can be debated and there are always trade-offs when it comes to making things more or less complex through comprehensive data.

But fundamentally, understanding territorial inequalities is at the heart of maintaining cohesion and competitiveness across a diverse federation such as Canada. We need a big-picture view of how socio-economic trends affect places in different ways to make the necessary effective and strategic policy choices.

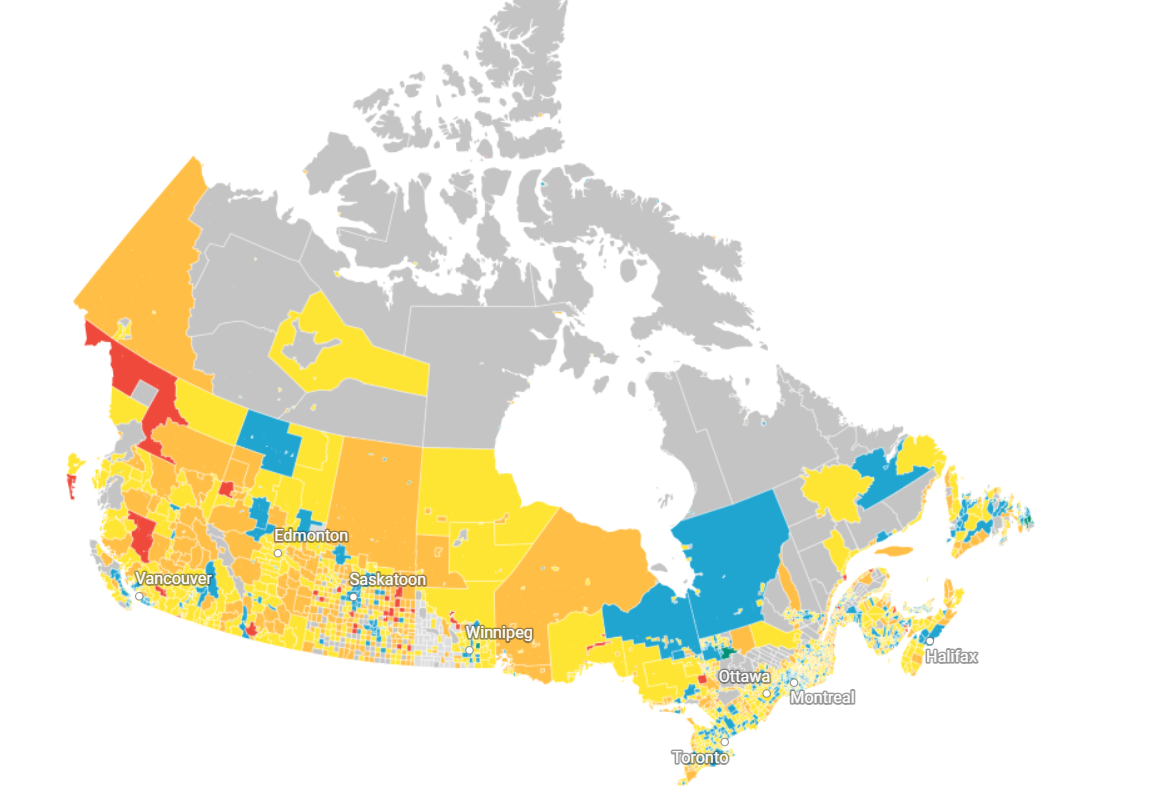

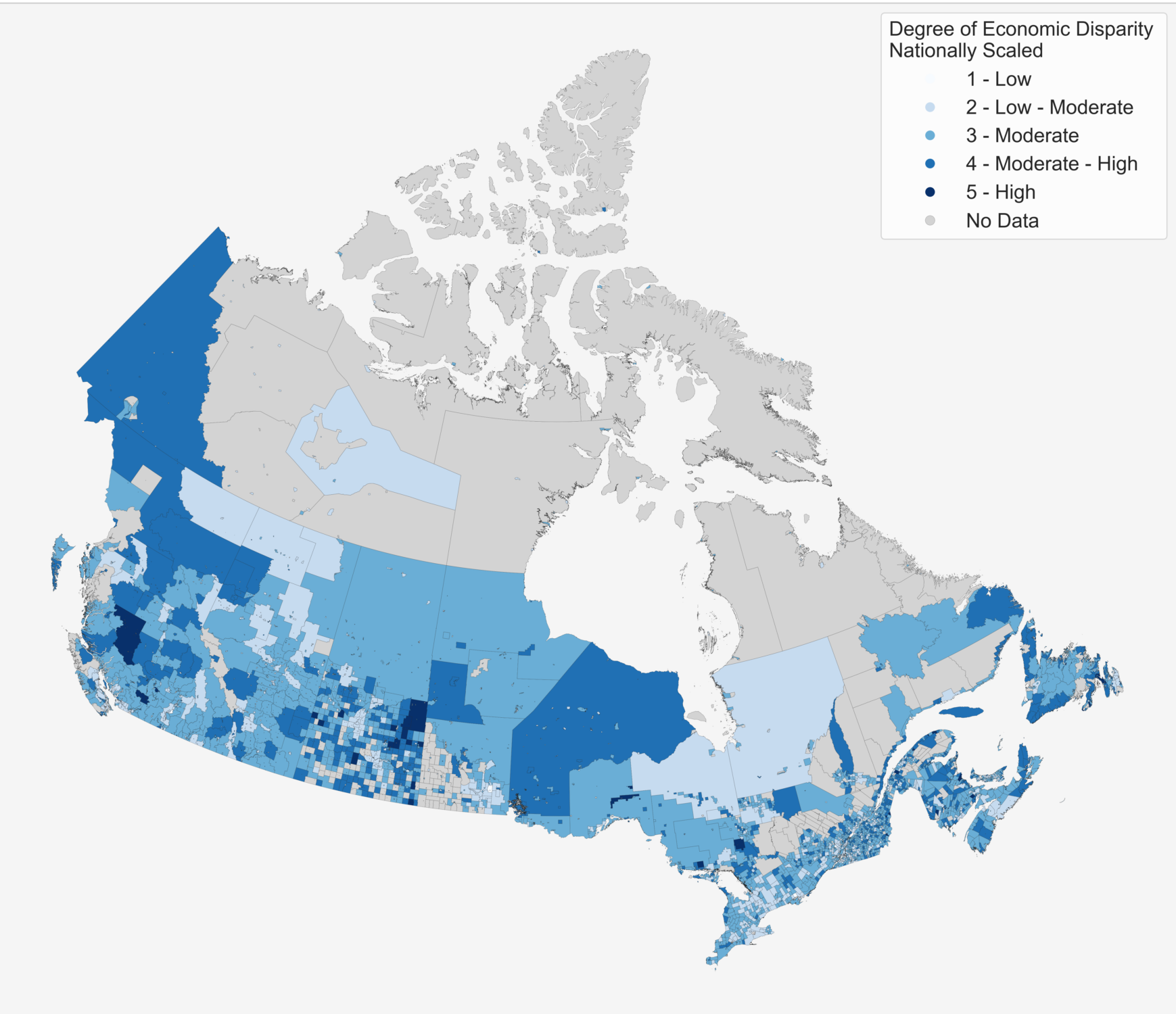

The Index of Economic Disparity scores depict the severity with which a census subdivision (CSD) is at risk for and/or experiencing significant and persistent economic decline. (Figure 1 shows an interactive version of the index, relative to each zone’s province or territory. We also created an index for each zone relative to Canada, shown in Figure 2 below.)

Our analysis finds only a small number of CSDs experience significant economic disparity (five on a scale of one to five), but around one-fifth experience moderate to high risk of economic decline (four on a scale of one to five).

This index is just one lens through which we can better understand territorial inequalities in Canada, a subject of growing concern in other OECD countries.

Given this, it is somewhat surprising that there are so few pan‐Canadian indices of economic disparity. Some recent examples include the Canadian marginalization index; the community well-being index; the regional economic capacity index; the Canadian index of multiple deprivation; and the index of community vulnerability.

While no one index provides a comprehensive portrait of economic disparities, each one sheds light on specific socioeconomic patterns, such as economic dependency, material resources, labour force activity or income.

Many governments across Canada have their own internal indices. They are used, for example, to identify communities that may have lower capacity to apply for funds and that need stronger support. These indices are often not shared publicly to avoid stigmatizing the affected communities.

That’s contrary to the practice in other parts of the world. In the European Union, for example, the identification of “leading” and “lagging” regions is commonplace and used to structure program supports.

For example, the European Commission (EC) identifies low-income lagging regions to target regional planning initiatives as part of its territorial agenda 2030, which aims to achieve sustainable development goals. Similarly, it identifies transition regions to deliver programs in places most at risk in the shift to a low-carbon economy. There is much less stigma attached to such identification in the EU.

Why is this important? Places that feel left behind can face disengagement and discontent in the long term. Left unaddressed, this can lead to support for populism, heighten rural-urban divisions and undermine democracy — a phenomenon that Andrés Rodríguez-Pose has called “the revenge of the places that don't matter.”

In a European context, the term “geographies of discontent” – a term coined by Philip McCann – has arisen to describe these dynamics. In Canada, territorial inequalities have long been a subject of study and concern, including deepening rural-urban and east-west divides. Yet, policymakers have remained reluctant to openly name, understand and confront them so directly.

There is an urgency to do so.

Mechanisms to overcome territorial inequalities are baked into our federation – from equalization payments to some provinces, to the Canada health and social transfers. However, Canada has largely abandoned its broader post-war commitment to regional equity – a vision where Canadians from Victoria to Corner Brook, N.L., should have equitable access to quality health care, education and economic opportunity.

In the face of large structural changes such as industrial shifts and the decarbonization of our economies, there is an urgency to chart divergences and proactively intervene in places facing persistent economic decline.

This requires sensitivity. There can be fear amongst politicians, public servants and citizens that openly discussing decline will turn prophetic. At the same time, governments fear committing resources to what may be seen as a lost cause when the only ”acceptable” mantra is growth.

Understanding economic disparity is particularly important when it comes to rural communities that tend to have less-diversified economies and can be at higher risk from economic/industrial shifts. Communities that are more remote tend to have higher scores on our index of economic disparity. This would lead one to conclude that rural communities in general have been declining or at least growing more slowly than urban communities.

However, this statistical relationship is weak and there is immense variation.

Rural communities are far from homogenous, which is why place-based policymaking is so critical. Within this, it is particularly important to consider Indigenous Peoples and communities. Approximately 60 per cent of Indigenous Peoples live in rural or remote areas, compared to 27 per cent for the non-Indigenous population.

Although the well-being of Indigenous communities is improving, significant gaps remain and these gaps are larger in non-urban areas. The index of economic disparity has limitations that are specific to First Nations and Inuit communities in terms of census data quality. Of the 861 CSDs in the 2016 Census that are missing an index score, 47 per cent are in Indigenous communities.

Even among Indigenous CSDs, the interpretation of index scores can be different from non-Indigenous communities. For instance, high population-dependency ratios among Indigenous CSDs are more likely to be driven by youth than by the elderly population. There is certainly more work to be done to think about how such indices can meaningfully be applied to Indigenous contexts.

This is a longstanding challenge. A 2018 report by the federal auditor general describes Canada’s community well-being index as “limited,” its sampling methods “poor” and its engagement with Indigenous organizations and communities in the production of the index “inadequate.”

Canada is a large and diverse federation. This diversity is generally a strength, providing economic and cultural resilience. It becomes a great risk, however, where there are long-standing disparities.

Comprehensive and complete data is key to better understanding, interpreting and acting to reduce these risks. Accurate snapshots of trends and relative territorial differences help see the big picture – enabling policymakers to bring forth effective, long-term solutions.