On the occasion of its 25th anniversary in 2010, the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada convened a high-level forum in Vancouver to discuss the state of Canada-Asia relations. The participants arrived at a number of key conclusions: that the importance of Asia in the world is greater than ever; that Canada has fallen behind many of its G8 peers in economic and political ties with Asian countries; and that efforts to build stronger relations with Asia have been sporadic and lacking in focus. The most dispiriting conclusion, however, was that these same points have been made many times over the years, and that progress seemed illusory.

But this group of leaders from business, academia and government were not content with a mere repetition of wellworn observations and gratuitous criticism. Rather, they agreed that there was an urgent need for a national effort to raise the awareness of Canadians about the importance of Asia, especially for the next generation of leaders, and to create the conditions for sustained political leadership on Canada-Asia relations. In the weeks and months that followed, many of the participants would ask how the foundation intended to follow up on the Vancouver meeting. It soon became clear that if we did not take the initiative of leading a national conversation on Asia, nobody would.

It is commonplace in the think-tank circles we inhabit to look first to the federal government for solutions to international policy challenges such as the Canada-Asia relationship. There is no question that there are a number of key policy decisions on trans-Pacific relations that only Ottawa (together with the relevant provincial authorities) can take, for example on the hard and soft infrastructure needed for energy exports to Asia; on trade agreements with Asian countries, including the Trans-Pacific Partnership; on seeking membership in Asian regional institutions such as the East Asia Summit; and on the approval of Asian state-owned companies looking to invest in Canadian assets.

The more fundamental and immediate challenge in building stronger Canada-Asia relations, however, is the need to develop a more Asia-literate and more Asia-engaged populace. This task cannot be left to government alone. Indeed, the recurrent problem of sporadic focus, lack of national vision and inconsistent Asia policy is not surprising given the relatively low levels of affinity that Canadians have for Asia, as our national opinion polls reveal. More recently, the fracturing of political consensus across party lines on a range of international issues — including China policy — creates new urgency for a non-partisan discussion on the long-term interests of Canada in Asia and the need to establish the conditions for sustained leadership on trans-Pacific relations across party lines.

The problem is not that political and business leaders do not understand the global rise of Asia, led by China and India and including other emerging powers such as South Korea and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. It used to be the case, barely five years ago, that I would have to spend the first half of a meeting with many senior officials or business executives simply making the case that the economic and political rise of Asia was real, and that it would have a profound impact on the world. Today, these leaders have no need for my “pitch”; they are much more interested in discussing what to make of Asia’s rise and, more importantly, how to respond.

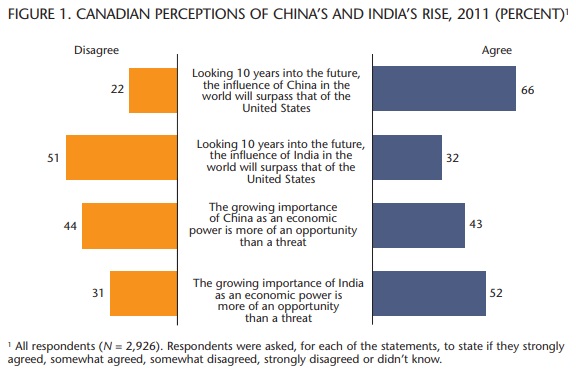

The perception of a net threat is in fact driven by respondents in Ontario and Quebec, where the bulk of Canada’s manufacturing sector resides and which arguably are the most vulnerable to Chinese competition. In every other region (British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan/Manitoba and Atlantic Canada), respondents saw the economic rise of China as a net opportunity.

Likewise, the Canadian public is by and large aware of the major geopolitical shifts that are taking place in the world, and of Asia’s centrality in those shifts. The Foundation has been conducting Angus Reid national opinion polls of Canadian views on Asia for a number of years and we have found that in Canadian minds, China looms ever larger as a global power (figure 1). In February 2011, 66 percent of Canadians agreed with the statement that “the influence of China in the world will surpass that of the United States” in 10 years, up from 60 percent just one year ago. The number of Canadians who see India’s influence exceeding that of the United States has also risen, from 30 percent in 2010 to 32 percent in 2011.

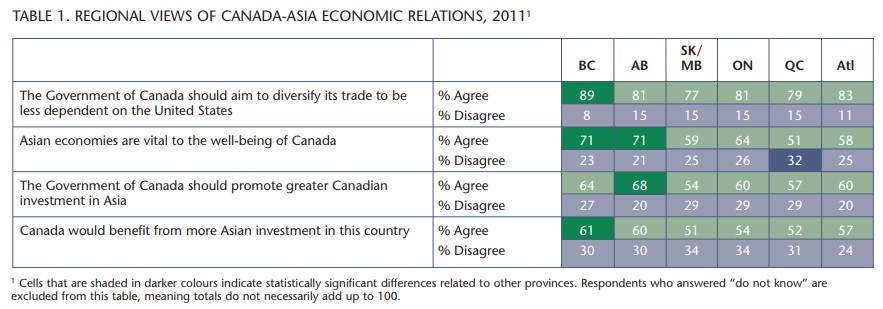

Other findings from our opinion poll suggest that Canadians recognize the importance of Asia, and China in particular, for Canada’s prosperity. Sixty-two percent of respondents agree that Asia is vital to the well-being of Canada, and China ranks second only to the United States in terms of importance for Canada’s prosperity. Whereas 77 percent of Canadians placed the US in the 6-7 range of a 7-point scale of importance, 44 percent chose China, and 35 percent the European Union. This finding should also be seen in the context of the 82 percent of Canadians who believe the country should try to lessen its dependence on trade with the United States. So far, so good. Other findings of the national opinion poll, however, point to contradictions in Canadian attitudes toward Asia, or at least to an incomplete understanding of how the rise of Asia will impact Canada, and how Canadians should respond.

We asked if the growing importance of China as an economic power is more of an opportunity or a threat, and found that the balance of opinion has shifted from “opportunity” to “threat” in just three years. Whereas 60 percent of Canadians in 2008 saw net benefit from China’s economic rise, that number fell to 48 percent in 2010, and to 43 percent in our most recent poll. In the case of India, Canadians still see net benefit from the economic rise of the South Asian giant, but only just, and with a slight decline between 2010 and 2011 (from 55 percent to 52 percent).

Accordingly, support for increased trade and investment ties with China and other Asian countries, while high, has been declining in the last three years. The number of Canadians who agree that the government should promote more Asian investment in the country has fallen from 59 percent in 2008 to 55 percent in 2011. We also found that the perceived importance of China, India, Japan, South Korea and Southeast Asia for Canada’s prosperity has fallen since 2008, even if in relative terms, Asian countries (notably China) rank highly relative to other trading partners. In fact, Canadian views of the economic importance of the United States and the European Union have also soured in the last year. In addition to special factors that apply to each of these trading partners, there may be the broader effect of an inward-looking sentiment that has been fostered by the global recession of recent years and by the relatively good performance of Canada through the downturn.

In the case of the United States and the EU, where the economic prognosis continues to be uncertain at best, it is perhaps unsurprising that Canadians are less inclined to look in these directions for economic opportunity. The same explanation, however, cannot be applied to China and India, or to most of Asia, where economic growth has been robust and where business prospects are brighter than in any other part of the world. Indeed, it is Asian growth that has by and large kept the world from a deeper recession, and that has allowed Canada — because of the resource boom — to have a relatively painless downturn. It is therefore a puzzle that Canadians are less inclined to see Asian countries as key trading partners when Asian markets are more important than ever. One explanation has already been proffered, which is that many Canadians see the net impact of China’s rise as a threat rather than as an opportunity. While we did not probe more deeply into this question, it is likely that the threat perception has to do with the fear that Chinese competition will displace Canadian jobs — not unlike the concerns often expressed south of the border.

A breakdown of the poll results by region is revealing. The perception of a net threat is in fact driven by respondents in Ontario and Quebec, where the bulk of Canada’s manufacturing sector resides and which arguably are the most vulnerable to Chinese competition. In every other region (British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan/Manitoba, and Atlantic Canada), respondents saw the economic rise of China as a net opportunity. Indeed, in energy-rich Alberta, the margin of “opportunity” over “threat” was a decisive 12 percentage points.

Regional differences can be found in a number of other poll findings (table 1): Quebecers are least likely to see Asia as vital to Canada’s prosperity (51 percent versus national average of 62 percent); Ontarians are most likely to disagree that China’s influence will surpass that of the United States in 10 years; and both Quebec and Ontario are most likely to discount the importance of placing more emphasis on teaching about Asian and Asian languages in the education system for building stronger ties with Asia.

There is perhaps a deeper explanation, however, for the general antipathy toward Asia that goes beyond threat perception. The poll included a number of questions that sought to gauge Canadian sentiment toward Asian countries and their perceptions of Canada’s place in the Asia Pacific region.

When asked to rate their feelings toward a list of nine countries/regions on a scale of 1 (cold) to 10 (warm), Canadians placed Australia at the top, followed by Great Britain, the United States and France. China, Southeast Asia, India and South Korea had only around 10 percent of respondents expressing warm feelings (8-10 on the scale) and 20-30 percent expressing cold feelings (1-3 on the scale). Japan came out the best among Asian countries, with 28 percent of respondents expressing warm feelings.

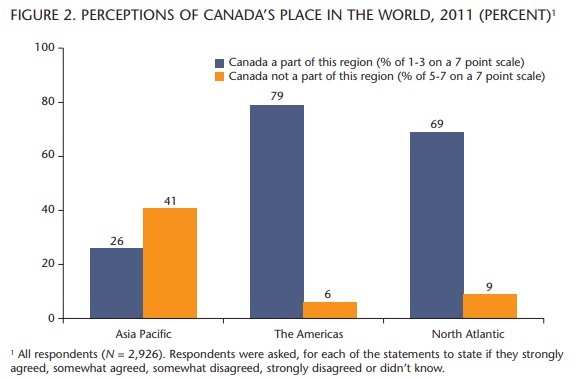

More fundamentally, Canadians do not seem to identify with the Asia Pacific region, despite the lip service given to Canada’s geographic and historical links across the Pacific. When asked if Canada is part of the Asia Pacific region, only 26 percent agreed (5-7 on a 7-point scale), compared to 79 percent who said Canada was part of the Americas and 69 percent who agreed that Canada was part of the North Atlantic region (figure 2). Furthermore, whereas 6 percent disagreed in identifying with the Americas (1-3 on a 3-point scale) and 9 percent disagreed about the North Atlantic, 41 percent of all Canadians rejected the idea that Canada is part of the Asia Pacific region.

There are regional differences at play on this question, but they are much more skewed between British Columbia on the one hand and the rest of the country on the other. The share of the population that sees Canada as part of the Asia Pacific region is significantly higher in British Columbia than in every other part of the country.

It is not surprising that BC has the strongest identification with the Asia Pacific region, given that it is Canada’s Pacific province and has a substantial proportion of residents who are of ethnic Asian origin. The low levels of identification in other parts of the country, however, pose a challenge in creating greater national focus on Asia, especially by the federal government. All too often, the allocation of scarce political and policy attention tends to favour the path of least resistance, and to cater to popular sentiment rather than being based on a strategic outlook.

Is it too much to expect that Canadians will ever identify with the Asia Pacific region in the way that they currently identify with the North Atlantic? Perhaps so, but demographic change and growing economic ties will make a difference, and it is likely that these “inexorable” forces will pick up the pace in the years ahead. The share of Canadians of Asian ethnic origin is expected to be 21.1 percent by 2031, up from 11.4 percent in 2006, as a result of immigration and natural population increase. And the number of Canadian businesses looking to Asian markets for growth opportunities will also increase, if for no other reason than stagnant or slow-growing markets in the United States and the EU. The tipping point is reached when Canadian firms see Asian markets as essential to their business, rather than as peripheral markets to be pursued only when the US economy is soft. We are starting to see this phenomenon in some resource industries in western provinces. The forest products industry, for example, has survived the US housing crisis of the last three years because of China. At least a dozen mills in British Columbia are functioning today only because of Chinese demand. There are fewer cases of tipping points in the manufacturing sector, but Bombardier is an example of a Canadian manufacturer placing huge bets on the Chinese market, and a number of auto parts suppliers in Ontario are setting up facilities in Taiwan and mainland China to tap into burgeoning Asian markets. In a 2010 survey of Canadian businesses in China conducted by the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada and the CanadaChina Business Council, we found some evidence of tipping points: 20 percent of respondents said more than 50 percent of their global revenues came from their Chinese operations.

Even without the promise of deeper people-to-people and commercial ties with Asia, the historical case for Canada as an Asia Pacific nation is strong. The founding myth of the transCanada railway as a physical extension of Confederation and the impetus for nation building is only partly correct. From the perspective of Canadian Pacific, which built the railway, the objective was much less the unification of Canada than it was to connect the markets of Asia with North America and Europe. After all, the person who was not in the iconic “last spike” photograph was none other than the president of the railway, George Stephen. He had more important things to do at the time, namely being in London to secure a subsidy for the ships that would pick up where the railway left off for the journey across the Pacific. “The C.P.R. is not completed,” Stephen wrote to Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, “until we have an ocean connection with Japan and China.” To extend Pierre Berton’s imagery, the “national dream” could be realized only by connecting Canada to Asia. Or to put it another way, Asia has been part of Canada’s identity for almost as long as Confederation itself.

Regardless of national identity, the need for greater attention to the rise of Asia and its impact on Canada is imperative. The case can be made on the grounds of economic and political self-interest, if not on history. Canadians are partway there in their appreciation of the new global reality, but there is another stretch to be travelled, and it will require some difficult re-examination of premises and priorities. For example, if two-thirds of Canadians believe that the influence of China in the world will surpass that of the United States by 2021, what are they doing about it? Not, it would seem, preparing the next generation for a more Asia-centric world, since 60 percent of Canadians do not see placing more emphasis on teaching about Asia or Asian languages as important to building stronger ties with Asia (BC and Alberta are the exceptions).

In some respects, the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada’s 2011 national opinion poll paints a bleak portrait of Canadian views on Asia. But we believe it also underscores the urgent need for a concerted effort to engage Canadians on the impact of the rise of Asia on Canada. The National Conversation on Asia is our response to the challenge, and we are calling on others to join with us in convening Asia-focused activities under the big tent of the National Conversation. By addressing issues specific to the interests of business, civil society, the education sector and government, we believe we can bring home the importance of Asia, not in an abstract way, but where it affects the priorities and passions of Canadians. Let the conversations begin.

Photo: Shutterstock