After the votes are counted tonight, 338 candidates will be headed to Ottawa to claim their seats as members of Parliament. The other 1500-plus candidates will be headed home. For some of them, that will mean coming to terms with a rough financial picture.

Running for office in a competitive campaign is very expensive. Serious candidates have to leave or quit their jobs, forgoing income for weeks or months. Some won’t have jobs to return to, if they weren’t fortunate in having flexible employers. The self-employed will have to make up for lost time and lost clients.

Drumming up sympathy for politicians is a difficult business. But it’s important to see the costs of standing for election, because those costs mean that few of us will ever be in a financial position to run — or to do so seriously. Our political class is drawn from those who have the means. The result is a form of underrepresentation in our national politics that often goes unnoticed or unchallenged. We need to find ways to make running for office more accessible.

The Samara Centre has been working with research partners and a team of volunteers to compile demographic profiles of all 2019 federal candidates in the major parties, based on information made public in candidates’ biographies. This data, which is not yet published, reveals the predicted underrepresentations — of women, Indigenous people and people of colour. But it also reflects class- and occupation-based underrepresentations. We can’t identify the income levels of candidates, of course, but we can make some inferences based on the information available to us.

What about service workers in retail or hospitality? What about child care workers, or tradespeople? They’re largely absent from Canada’s political class.

For example, on the basis of publicly available information alone, it becomes clear that most candidates hold one or more university degrees; by comparison, fewer than 30 percent of working-age Canadians have those credentials. Lawyers, entrepreneurs and private sector executives are well represented among candidates. So are office holders from other levels of government, and some middle-class professionals like teachers. But what about service workers in retail or hospitality? What about child care workers, or tradespeople? They’re largely absent from Canada’s political class.

None of this is remotely surprising. But it should bother us more than it does.

Education and income are strong predictors of Canadians’ attitudes toward political issues and of their general views of Canadian democracy. They are stronger predictors, in many cases, than the other identities we carry. There’s evidence that working-class politicians behave differently in office, that their life experiences inform different priorities. Our white-collar parties and Parliament make substantively different decisions than they would with a more economically diverse membership. And working-class Canadians don’t see themselves reflected in their leaders, strengthening the existing tendency toward greater political dissatisfaction and distrust.

These demographic absences are reflected in how politics is done, and for whom. Indeed, the lack of a lived experience of the working class is apparent in the political discourse today, which has become peculiarly conscious of just a single class: the middle class (whoever that is). It’s also reflected in the woolly notions held by political elites about what a working-class Canadian is in 2019 (it almost always involves a hard hat).

Much of the responsibility for recruiting a more diverse candidate slate falls to the parties. But fixing economic underrepresentation, deliberately and through policy, is not easy. It involves wrestling with social and economic structures that are pervasive and deeply entrenched — beyond the reach of most available political reforms.

Nevertheless, we can think creatively about policy avenues to make political candidacy more affordable and more accessible. We can start by replacing some of the income that is lost when someone seeks office. Employment insurance provides income support for people who are unexpectedly unemployed. But it is also a tool to replace income for people who have to step away from work temporarily, to do something that is personally costly but beneficial to society — like raising a baby or caring for a sick family member. This logic can be applied to political candidacy.

The federal government should consider a new carve-out in the Employment Insurance Act, to allow registered (non-incumbent) candidates for federal, provincial and municipal elections, if they are otherwise eligible for EI, to collect it for a limited period (say, for a maximum of 50 days, which is also the maximum length of a federal campaign). Right now, candidates aren’t formally disqualified from collecting EI. But they have to be available for work and job-searching in the usual ways while collecting the benefit. Anyone who is truly campaigning full-time, with the goal of actually winning and holding office, is essentially ruled out.

This should be changed. There would be some potential for abuse, but that’s no different from the conventional uses of EI. In fact, when it becomes necessary, distinguishing between real and fake candidates would be, relatively speaking, easier to adjudicate.

It’s really important that good people put their hands up to run in our elections. It’s really important that those people aren’t only the relatively wealthy. Replacing candidates’ income is a small change. Obviously, it wouldn’t be enough to overcome the huge structural obstacles facing working-class Canadians: precarious employment, lack of time and a want of political resources like personal access and fundraising networks, to name a few. The take-up would likely be small. And it may prove that more targeted measures are needed to move the needle on working-class representation.

But it’s a simple policy step to help relieve the immediate financial costs of candidacy. It would also send a message to some of the people who most need to hear it: that whatever the political class looks like today, it’s supposed to be of you, and for you — and, in fact, it needs you.

This article is part of the Election 2019 feature.

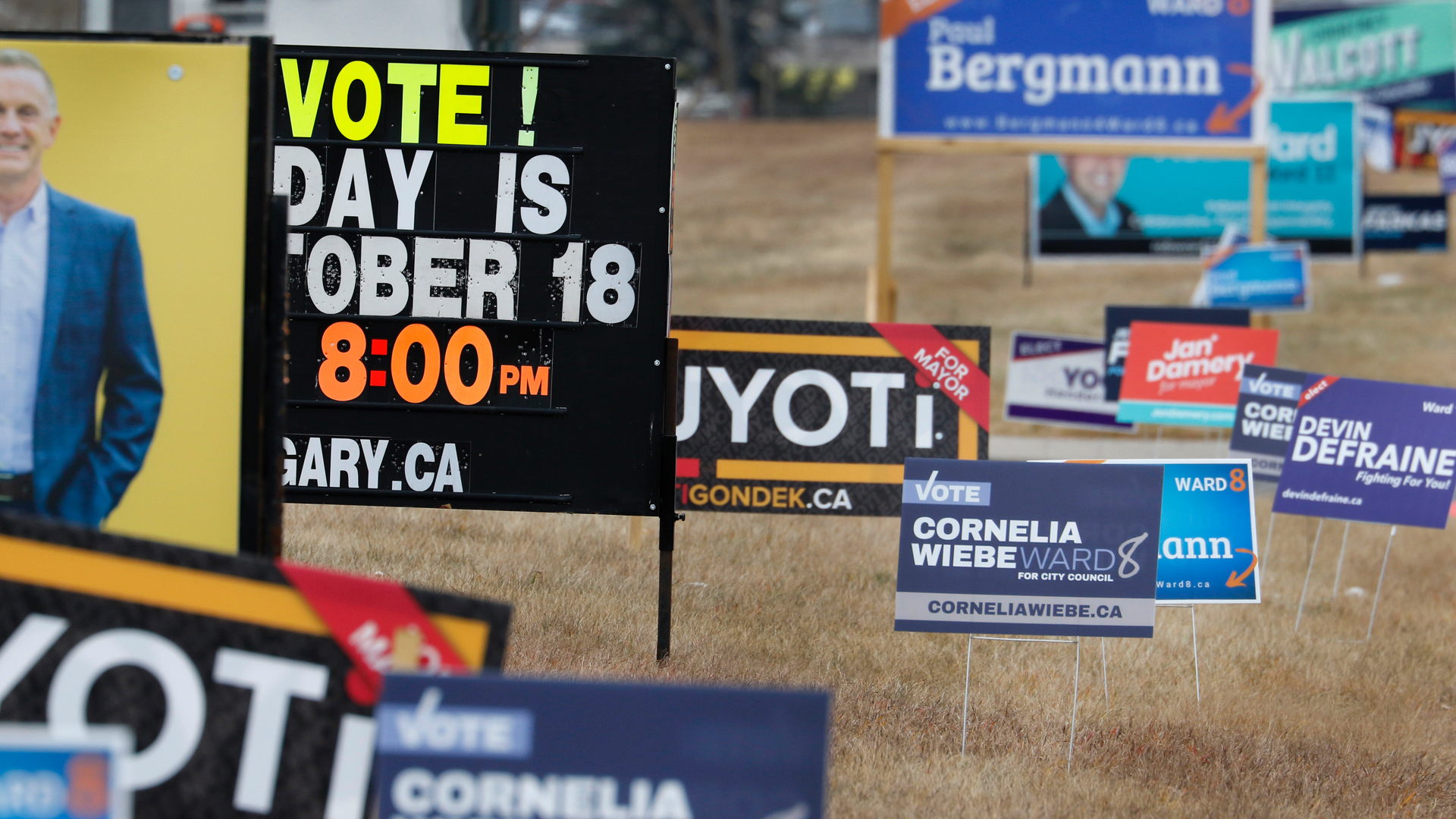

Photo: Electoral signs for candidates are shown on the streets of Saguenay, Que. on October 7, 2019. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Jacques Boissinot

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.