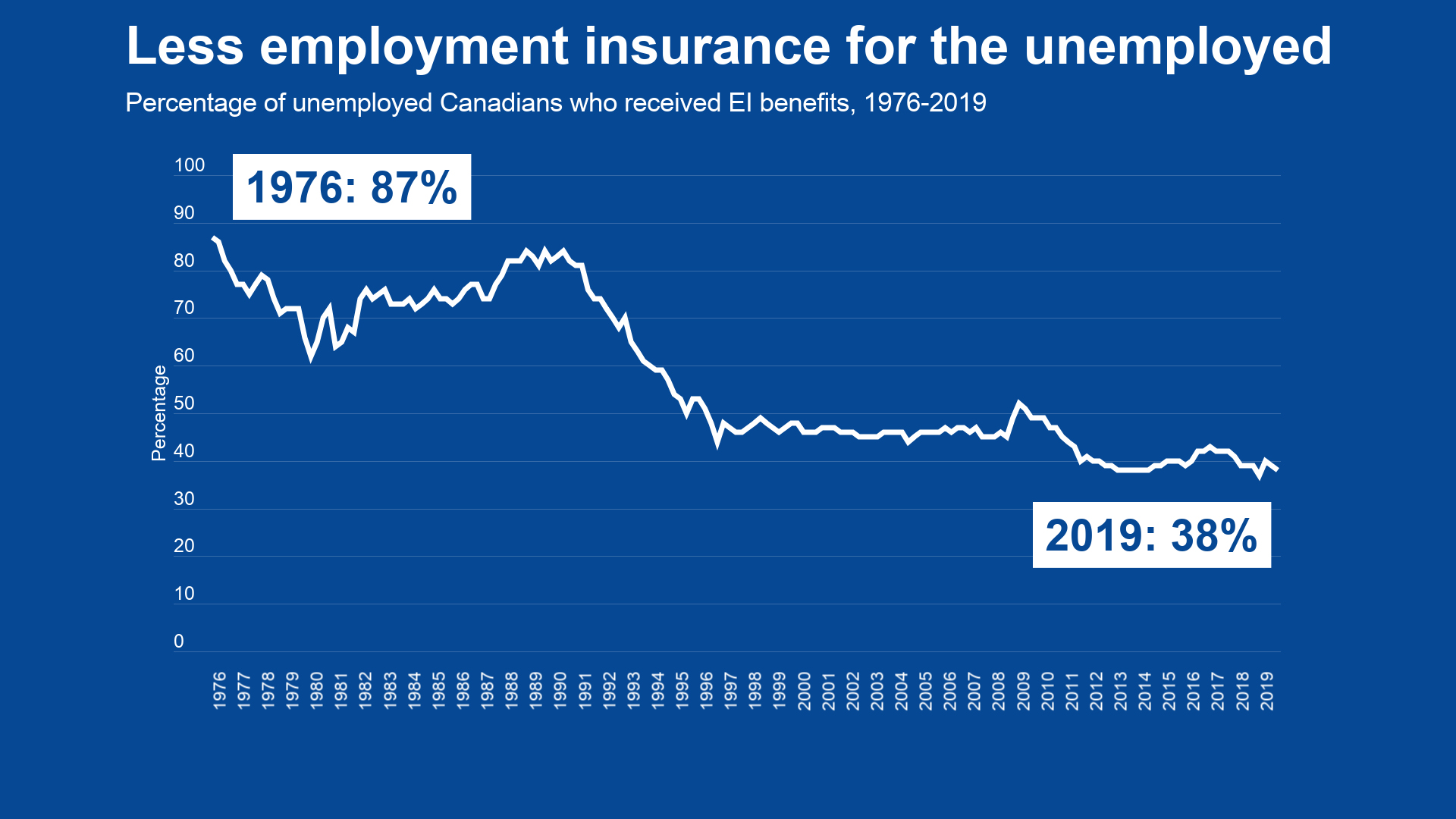

When the pandemic broke out, causing millions of workers to temporarily lose their jobs, the percentage of unemployed Canadians who were receiving employment insurance was less than 40 per cent — down from more than 80 per cent in the 1990s.

In the face of the greatest shock to the Canadian economy in decades, the EI program failed to provide benefits to a significant share of the nation’s jobless and could not process the surge in claims in a timely manner. But EI’s shortcomings have been evident since long before the onset of the pandemic. The federal government is undertaking a two-year review of the program to consider, among other things, the increasing number of Canadians who work in non-traditional jobs and don’t qualify for EI.

The Institute for Research on Public Policy convened a working group of 12 experts to propose options for modernizing the program, and recently published a report highlighting the program’s challenges as well as the proposals that they put forward. One message came through loud and clear: The current program is too complex and suffers from too many gaps in coverage that have made it increasingly ineffective, especially during recessionary periods.

A lot has changed since EI was last revised almost 30 years ago. For one thing, there’s been a surge in the number of app-based companies like Uber and DoorDash whose workers are deemed to be self-employed and not eligible to receive EI benefits because they don’t contribute to the fund. The program wasn’t built for these workers.

Stop-gap measures were needed to address the income support needs of jobless workers during the pandemic. Over the past two years, the federal government has introduced various contingency measures and programs to accelerate claims and benefit delivery, fill the gaps in support and create new programs for unemployed Canadians who didn’t qualify for benefits. Many of these measures have already expired and the remainder are set to end in September 2022.

The structure of Canada’s labour market was much different when the EI program was introduced in 1940 in the wake of the Great Depression (see figure 1). Its scope expended greatly over the years and has come to include a complex patchwork of maternity, parental, sickness and compassionate-care leaves, income support for seasonal workers and funding for employment-training programs. Eligibility rules and the generosity of the various benefits have expanded and contracted over the years based on the prevailing economic and fiscal conditions. Its complexity, along with the growth in new work arrangements and changes to eligibility criteria have combined to hamper its effectiveness. As a result, the proportion of the unemployed who collect benefits has declined.

What can be done to make EI more effective and responsive to today’s economic realities?

Participants in the IRPP’s working group generally agree that the program should be simplified and the eligibility rules eased to make them more universal across the country. They also urge the federal government to consider options for making benefits more generous either by extending the duration of benefits, increasing the current earnings replacement rate of 55 per cent, increasing the level of maximum yearly insurable earnings, currently set at $60,300 — or some combination of the three.

Access to special benefits, such as maternity and parental benefits, should also be improved, they say, noting that benefit levels are too low and that regulations governing them are too complex. Rules that stipulate how various EI regular and special benefits can be combined put some claimants at a disadvantage. For example, if a woman who has received maternity or parental benefits is laid off before or shortly after returning to work, she would be ineligible for regular benefits because she wouldn’t have accumulated enough hours of work to qualify.

COVID-19 and support for the unemployed

Redesign parental leave system to enhance gender equality

Between 1976 and 1990, the percentage of unemployed Canadians who received EI benefits was about 80 per cent on average. That number fell to below 50 per cent between 2000 and 2010, and to roughly 40 per cent between 2011 to 2019 (see figure 2). The participants agree that it is time to address systemic exclusions, including self-employed workers, particularly those in precarious jobs. Before the pandemic, unemployed workers who do not pay premiums into the regime, a group that consists of self-employed workers and those without insurable earnings in the previous 12 months, comprised over 35 per cent of unemployed workers. However, finding ways to include them won’t be easy.

Experience in other countries suggests that having a voluntary program for the self-employed won’t work because those in secure jobs are likely to opt out. However, a mandatory program that requires self-employed workers to pay the necessary contribution rates is likely to be equally as unpopular. Although Canadian self-employed workers have been able to opt in to special-benefit programs since 2010, take-up has been low; less than 0.1 per cent of eligible workers have done so.

Of course, some of the proposed changes would mean higher program costs and, as a result, higher premiums for workers and employers who pay into the fund. The participants discussed various ways for how these measures could be funded, with some calling for a return of federal government contributions, which ended in 1990.

Building flexibility into parental leave

The federal government initially funded the program’s administrative costs and matched 20 per cent of annual employer and employee contributions. But by 1971, federal contributions were largely limited to covering the costs resulting from the rapid increase in the number of beneficiaries during periods of high unemployment. In 1990, as the federal government started to face up to its major fiscal challenges at the time, the program was made entirely self-financing, with workers and employers the sole contributors.

The shortcomings of the EI system are unlikely to recede even when the pandemic ends. Canada’s aging workforce, technological change, new forms of work arrangements, worsening labour shortages and expected job displacements resulting from Canada’s transition to a low-carbon economy are all expected to make the labour market more volatile and put additional stress on an already strained system. At the same time, the significant pool of self-employed workers and a shift to more short-term and contract jobs will mean that a large swath of workers could continue to be excluded.

Canada needs to modernize its employment insurance program to reflect today’s economic realities. We’ve done it before; it’s time to do it again.