(Version française disponible ici)

The Coalition Avenir Québec government has tabled the first budget of its second mandate.

A budget is more than just an accounting exercise. It is a document that, through the government’s revenue and spending choices, sets out an economic and social direction for years to come. It also reveals what is important to our leaders, and what is not.

If you’re one of the unlucky Quebecers who must pay full price for daycare or a nursing home space, known in the province by the acronym CHSLD, you’re not on the government’s radar. The government promises these services will get better – eventually. But it has decided that lowering taxes is more urgent.

So those unlucky Quebecers will continue to pay full freight for daycare spaces or CHLSD beds – and those of others through their taxes – with little chance of getting the same benefit.

Bon appetit

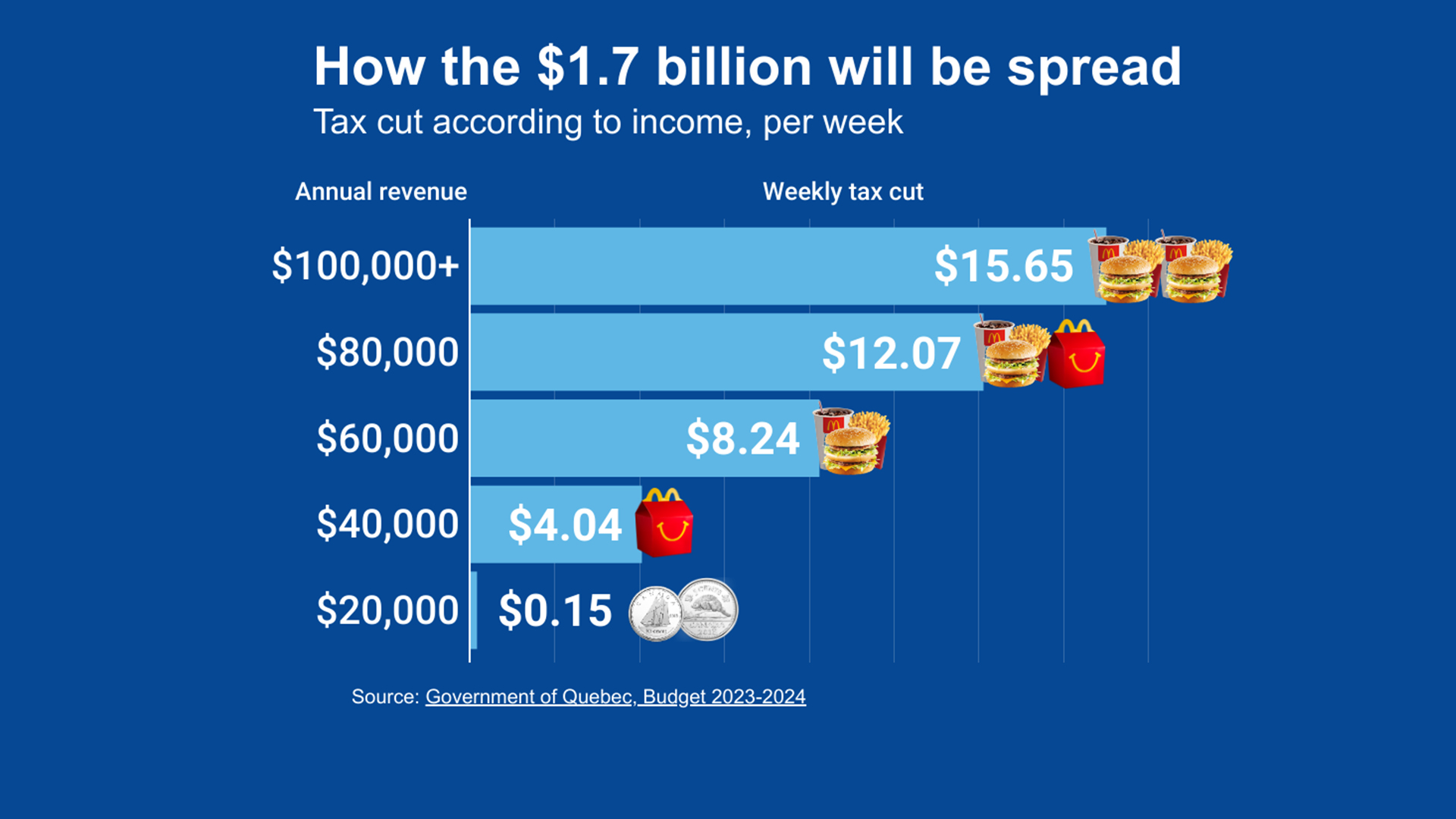

The CAQ tax cut represents $8 a week for a Quebecer earning $60,000 a year. That’s the equivalent of a Big Mac meal, if you have coupons.

Those earning $100,000 or more will save $16 each week, or two discount Big Mac combos.

The median income of Quebecers is about $40,000, according to the latest estimates. Those people will be able to save $4 a week. Barely enough for a Happy Meal.

It doesn’t sound like much, whether you count it in burgers or coffee. But if you multiply it by 4.6 million taxpayers in Quebec, the collective cost is considerable: $1.7 billion – more than enough to make those two key services universal.

It is not the right time for a tax cut

There is nothing wrong in principle with a tax cut. Quebecers pay a lot of taxes, much more than the average in the developed world, and more than elsewhere in North America. High taxes have drawbacks, including that they discourage people from working more and that the wealthiest often find ways to avoid them.

A case can also be made for high taxes when they are well-used. The World Happiness Report illustrates this eloquently. The countries with the happiest people are almost all in northern Europe, where taxes are also among the highest in the developed world. But their public services generally meet the expectations of their citizens, who have a good opinion of their governments.

In Quebec, we have the worst of both worlds: very high taxes and public services whose accessibility and quality are quite variable. This can be infuriating if you happen to look at your pay stub while waiting for hours in an emergency room.

Still, there are good and bad times for a tax cut. A period with the threat of a recession and a surge in demand for public services is probably not a good time. Even Quebec’s business council pointed out tax cuts were not a good idea right now.

A more rational – if pessimistic – argument for tax cuts is that given Quebec’s labour shortage, the government will be unable to deliver many services no matter how much money it takes out of paycheques. That will certainly be a challenge in Quebec’s schools and hospitals.

Universal services… that are not really universal

The government could nevertheless have made a difference for tens of thousands of Quebecers in the very short term, while making our public services more equitable.

Subsidized childcare for toddlers and long-term care for seniors are both cases where successive governments, long before the Coalition Avenir Québec, have chosen to partially provide these services. For citizens, obtaining them are a lottery. Or, more accurately, like a game of musical chairs: everyone pays for these services through their taxes, but there is not enough room for everyone. Those who don’t have a place pay full price, whether they’re rich or poor.

Unique, but incomplete daycare services

Quebec’s publicly funded childcare system is unique in Canada. It is one of the few public policies that actually pays for itself. It allows women to stay in the workforce with less interruption, bringing them career benefits (and tax revenue for governments). The employment rate of women in Quebec grew with the childcare program and remains higher than in other Canadian provinces and most rich countries.

But 25 years after implementation, the Quebec childcare network remains incomplete. The first children from the system are grown up and many turn to unsubsidized private childcare centers for their own children because of lack of public and subsidized spaces. The government issues a tax credit for these fees, which can exceed $50 per day, but the final cost is generally higher than in subsidized daycare.

$10,000 a month long-term care

Quebec also subsidizes end-of-life care for seniors but this essential service is also not universal.

There are about 400 CHSLDs in Quebec, housing just over 40,000 seniors. The Ministry of Health operates the vast majority. Contractors manage about 60 private CHSLDs that receive public funds, charge the same low rents and offer the same working conditions as publicly managed ones. (Contrary to common perception, these facilities offer comparable or even better care than the public homes.)

However, some 40 private CHSLDs are not subsidized. Unlucky elders who could not find a place in the public network pay up to $10,000 a month. Caring for people near the end of life is very expensive, and successive governments have been inexplicably slow to subsidize this final piece of the system.

The result is indefensible: tens of thousands of Quebecers pay taxes to finance public services to which they will never have access. It’s been that way for decades.

Political will is lacking, not money

In both systems of care, the problem is not a lack of manpower – at least, not more than elsewhere – but a lack of funding, and above all, a lack of political will.

Of the 290,000 childcare spaces in Quebec, about 66,000 are in the unsubsidized private sector. Converting them all to subsidized spaces would cost about $470 million per year, according to government estimates (these may be optimistic).

As for the CHSLDs, the unsubsidized private sector manages about 6,000 of 40,000 places. Subsidizing each of these places would cost the government about $100,000 a year, for a total of $600 million.

Combined, the cost of completing the networks of subsidized daycares and CHSLDs, allowing for a margin of error, is well within the $1.7 billion budgeted for tax cuts.

Waiting lists would not disappear, because need tends to grow faster than resources, and there is a labour shortage, and other labour market incentives are misaligned. But at least a major step toward equity would be achieved.

The COVID-19 disaster in senior care should make reform a top priority

IRPP study: Life and death during COVID-19 in long-term care

And public services that have always been presented as “universal” would actually become universal, or close to it.

Currently, the government has committed to converting 5,000 unsubsidized child care spaces next year. That leaves over 60,000 which will not. The 40 unsubsidized private CHSLDs have been asking to join the subsidized network for 20 years. The “harmonization process” put in place in the wake of the spring 2020 pandemic nursing home disaster converted three of them. There is no sense of urgency.

Families need help. Elderly people and their families are waiting for someone to take care of them. The government should rapidly implement solutions, even imperfect ones, in the name of equity over bureaucratic exigencies.

Quebecers can be proud that their social safety net is broader than those of other Canadians. They would be even prouder if the net caught everyone, instead of leaving out the unlucky.

That’s probably worth a Big Mac a week.