After much speculation and delay, Budget 2017 is expected March 22. When it finally lands, hundreds of people in Ottawa and beyond will analyze a long and complicated document — and be expected to do so as quickly as possible. This is a difficult task at the best of times, even for budget wonks. This article tries to make Budget Day a bit easier, by offering tips to help identify what matters most.

Tip 1: To deconstruct the budget, first consider its construction

Keep in mind that budget presentations are highly orchestrated. Masses of figures and facts are scrutinized by countless bureaucrats and politicians in the months before the final release. Fundamentally, this is an exercise in assembling the evidence that best supports the government’s narrative. In other words, the goal of the budget is not necessarily to provide a comprehensive, objective view of the economy or the government’s fiscal situation. There’s nothing nefarious about this approach. All governments do the same. But being aware of this fact will make you more sceptical of what you read, and that scepticism can be helpful.

Tip 2: Prepare

Before the budget is released, reflect on your role and that of your organization. What’s your unique interest and perspective? At the IRPP, we’re mainly trying to get a sense of the government’s overarching economic and policy concerns and its priorities. We want to reflect on whether these priorities are the right ones and which alternatives might be better. Those in the opposition parties have a different perspective: they’re probably looking for government vulnerabilities, places where the government isn’t doing what it said it would.

There are plenty of helpful resources to read in advance:

- Budget 2016 and the Fall Economic Statement are good places to start.

- The government will want to show clear progress on its mandate letter commitments, which identify key objectives for ministers.

- The Second Report from the Advisory Council on Economic Growth has some clues on what has been touted as an innovation budget.

- This Finance Canada report provides the background for an expected tax expenditure review.

- Organizations like the Parliamentary Budget Office and the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy (IFSD) release pre-budget outlooks, while think tanks like the C.D Howe Institute and the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives provide their own model budgets in advance of the government.

Tip 3: Numbers can tell you more than narratives

When you finally get the budget document, have a quick glance through summary texts like the press release or minister’s speech to identify the government’s main story lines. Then stop reading and dive into the numbers.

But there are so many numbers, where to start? If you’re really pressed for time, the following three stops are indispensable.

First stop: The economic survey

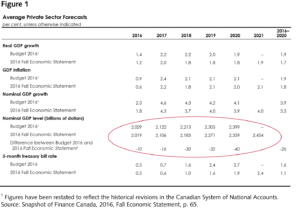

The natural starting point is Finance Canada’s survey of private sector forecasters, which forms the economic basis for the government’s budget projection. This table shows the economic outlook in considerable detail. To keep your task simple, look for one line. The most important summary indicator is the level of nominal gross domestic product (GDP) — and specifically how it’s changed since the last time.

The red circle in the example below (figure 1), taken from the 2016 Fall Economic Statement, shows that the level of nominal GDP was expected to be $40 billion lower towards the end of the budget projection in 2020. That one line tells you that the economic outlook has worsened. This means that the government will probably have less fiscal room. It may decide to scale back its spending plans to keep to its deficit target; it could stay the course and accept a larger deficit; or it could ramp things up and try to give the economy a boost.

Second stop: New fiscal measures

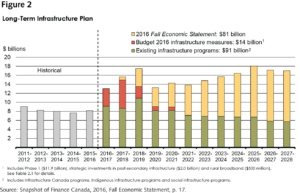

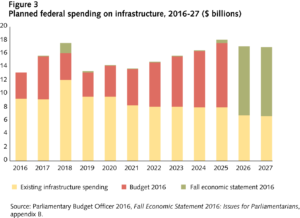

The second table to look for lists all of the new fiscal measures announced since the last budget/update. Again, lots of numbers. Look carefully to identify which programs really matter in the grand scheme of things. What are the biggest cumulative dollar amounts? When is the money actually being spent? These are important questions because government communications folks may try to highlight “new” spending that’s not so new, or that won’t be happening for several years. That was the case in the 2016 Fall Economic Statement, where the government touted “$81B over 11 years” in new infrastructure spending.

In the government’s original presentation (figure 2), the yellow bars represented “new” money; the red bars were money that was allocated in the previous budget; and green bars were money allocated by the previous government.

Interestingly, this wasn’t quite how things looked when the government later sent detailed numbers to the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO). Instead they looked more like figure 3:

This figure has much less yellow — or in other words, less “new” money over the next few years. The fall update was announcing for the most part how money that had already been announced in Budget 2016 would be spent. The government was not really committing itself to new spending in the near term; instead, it was committing the government after the next government.

Third stop: The bottom line

The third important table is the one most people go to first: the summary budget balance table. By making this your third stop, you will better understand how the economy is shaping up and how much new programs will cost and when they will occur. That information makes it much easier to understand why the government’s bottom line has changed since last time, a key point given the political focus on whether the deficit is bigger or smaller than before.

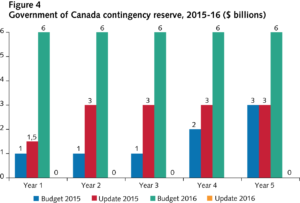

It can be tricky to compare quickly across budgets. You need to make some careful adjustments to avoid misinterpretations, because most budgets include “forecast prudence” (also known as a risk adjustment factor or contingency reserve), and these amounts usually vary from budget to budget (see figure 4). Changes in the government’s bottom line can be due to three factors: (1) economic changes, (2) new fiscal measures, and (3) changing amounts set aside for budget risks. (For details, see an analysis of Budget 2016 here).

Tip 4: Budget numbers are forward-looking forecasts

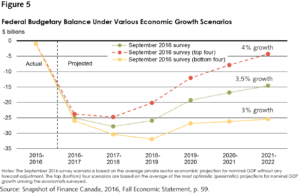

Numbers for total revenues and expenditures are estimates of what the government is planning for. No one knows exactly how the Canadian economy will ultimately perform — and different levels of economic performance can have a big impact on the government’s bottom line (figure 5). The only thing that can be said with certainty is that these forecasts will not materialize exactly as expected. Be mindful of this unavoidable uncertainty before making strong pronouncements about government policy choices.

Tip 5: See the big picture

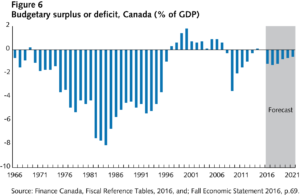

Try not to get caught up in the minutiae of small year-to-year changes; rather, keep a long-term perspective. Try to compare recent results or projections by looking back over history (figure 6). Some changes or new programs may sound important fiscally, but are they really? As an example, several budget pundits got worked up about the fact that Budget 2016 did not spell out a date to eliminate the deficit. However, if we consider these expected deficits not just in nominal terms but also in relation to the size of the economy, it becomes clearer that the fiscal sky isn’t falling. Yes, Canada lived through fiscal crises in the 1990s, but current circumstances are not in the same league, and taking the long view counteracts the urge to be overly dramatic.

A major perennial issue is whether the budget outlook is “fiscally sustainable” over the long-term — in other words, whether government debt as a share of the economy will be kept in check. For a recent analysis on this for the federal government see here; and for the overall government sector in Canada, see here.

To sum up, Budget 2017 will be an important second budget for the Trudeau government. The best advice is to think like a budget maker. Be prepared. Be skeptical. Dig into the numbers, which can often provide more insights than the narratives. And don’t lose sight of the bigger picture.

Photo: Fred Chartrand/The Canadian Press

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.