My last post on Policy Options Perspectives described what I’ll be looking for in Budget 2016, including things like budget transparency, prudence, clear fiscal policy targets and a better sense of key policy priorities.

This article explains something I’m not focused on in the budget — the projected budget balance in a given year. This commonly raises preoccupations like, “Did the Conservatives leave the Liberals a surplus or not? Will the deficit be larger than $30 billion next year? And will the government balance the books by 2019?”

Headline deficit numbers matter, of course, but on their own they are an incomplete story, as John Geddes of Maclean’s magazine explained in this recent interview:

“Sometimes we talk about deficit and stimulus as though it’s the same thing. It really isn’t the same thing. Some of the deficit is just because revenues are coming in more slowly. That can’t really be seen as stimulus”

So allow me to steal a phrase that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau used during one of the 2015 election debates, “A deficit is NOT a deficit, is NOT a deficit.”

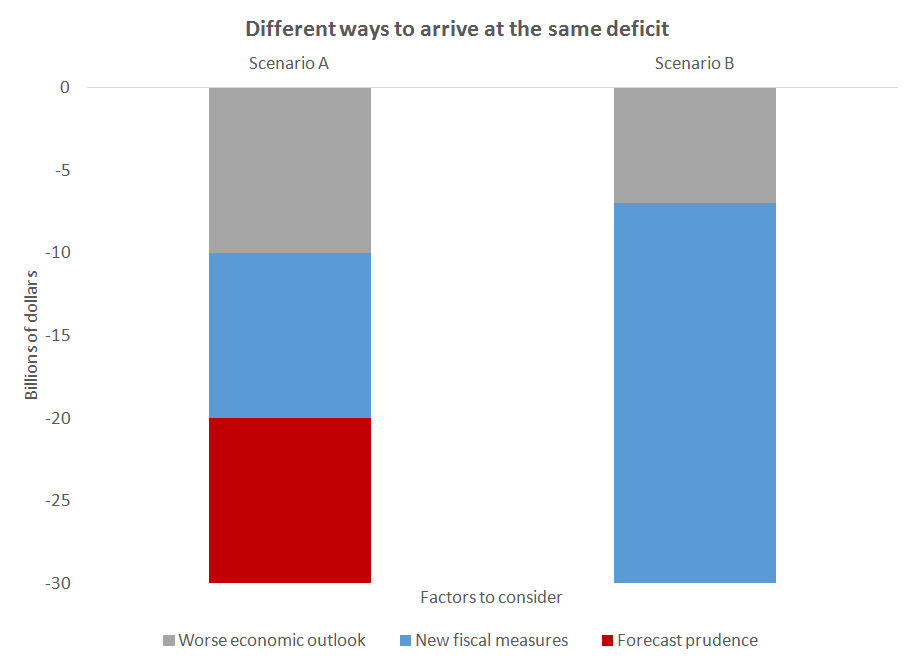

What matters, in other words, is the reason for the deficit. Consider three contributing factors: the worsening economic outlook, new fiscal measures introduced by the government, and forecast prudence (the extra padding you factor into the budget, in case things go south).

Here are two theoretical scenarios to show why it’s important to drill down into the factors behind a deficit:

In scenario A, one-third of the deficit is due to each of the factors. The cost of new measures for the upcoming fiscal year is similar to what the Liberals forecast in their election platform (roughly $10 billion). So the fiscal adjustment (relative to expectations based on the government’s last fiscal update) largely reflects some extra prudence they’ve factored into the budget. There’s no real change of plan from what they promised during the election campaign. They’re just being more cautious, so in all likelihood, the government would eventually better its deficit target.

In scenario B, the economic adjustment due to external factors — such as weaker oil prices — is smaller, but the government’s reaction through new fiscal measures is stronger. This scenario also has the government acting less cautiously – no additional prudence has been factored in. In this scenario, it looks like the Liberals are doing more than they promised in the election.

But is this because they underestimated the cost of their election promises and have updated their estimates, or is it because they’re actually doing more? Importantly, are these new measures temporary or permanent, and does the budget include higher taxes to fund the permanent part? These questions are pertinent because they help us assess whether the government’s measures might make it harder in the long run to eliminate the deficit.

Not all deficits are created equal. And in Budget 2016, in particular, we need to look beyond the headline deficit numbers. If we can figure out what’s driving them, we’ll get a much more complete picture of what’s going on.