We expected it was coming, given President Donald Trump’s campaign promise to withdraw from the Paris Agreement on climate change. Yet we followed the news each day, intensely, reading signals into Trump’s “game-show”-style tweets about the decision to come. And now it has. The US is withdrawing from the Paris Agreement under Trump, just as it refused to ratify the Kyoto Protocol under George W. Bush in 2001. In the past 15 years, what has changed, and what does Trump’s move mean for climate action, in Canada and globally?

First, it’s important to recall the US cannot formally exit the Paris Agreement until 2020. While the US remains a party to the accord in the interim, the administration could revoke or water down the Obama-era pledge to reduce emissions 26 to 28 percent from 2005 levels by 2025. However, such a move would run contrary to provisions in the Paris Agreement establishing a progression in pledges toward more ambitious targets, not lower ones.

And despite grand claims made during the election campaign, the Paris Agreement will not automatically perish as a result of the US departure. The accord came into effect on terms that did not require the near-universal support it actually garnered. The only countries in the world that are not signed on to the Paris Agreement, other than the US, are Nicaragua (which says the agreement doesn’t go far enough) and Syria.

Moreover, even if Trump lasts a full presidential term and sees the withdrawal through — neither is guaranteed — the US is still a party to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, the underlying 1992 treaty committing states to prevent dangerous interference with the climate system. Staying in the convention was a tactical move the US made to maintain a seat at the climate negotiations. The US has been a force in these negotiations from the outset and is threatened by calls for other states, especially China, to take the reins.

As we consider these details of the withdrawal, we can see similarities and differences between Bush’s and Trump’s responses to international climate law. For instance, when the US refused to ratify the Kyoto Protocol, it was not bound to pledges made under the protocol in the way the US is now, arguably, bound to its Paris pledges until its formal exit from the agreement. On the other hand, as the US air strikes in Syria show, Trump may prefer unilateral action to upholding international law and may disregard his country’s Paris commitments anyway.

And as was the case with the Kyoto Protocol, the Paris Agreement will continue to operate while the US seeks influence through the framework convention or, in this instance, as a party to the agreement before its withdrawal takes effect. Trump has vowed to renegotiate the Paris Agreement or create a new accord. Some say such a move could derail the continuing negotiations on detailed rules under the Paris Agreement, as the US advances its own interests to the detriment of global action.

At the end of the day, then, is Trump’s declaration just a rerun of Bush’s action in 2001?

Whether for better or for worse, the US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement is not history repeating. For one thing, climate action has become more urgent than at the turn of the century. We know this from increasingly reliable evidence of the imperative to reduce emissions immediately and significantly before 2020. The urgency to act has become visible in the effects of climate change that we see today: extreme weather, decreasing snow and ice in the Arctic and Antarctica, and rising sea levels. Because the US is the second-highest emitter of greenhouse gases, its inaction now poses a greater threat because time has passed and we have less of it.

Time is partly what pushed countries to reach the Paris Agreement, and the accord is a wholly new chapter in the UN climate regime. The Paris Agreement has been lauded, overwhelmingly, as a historic achievement in international cooperation, reached after over two decades of divisive negotiations among 197 parties. Whereas Kyoto required only industrialized countries to reduce emissions, and was often criticized for that reason, Paris applies to all countries. Differentiation between countries persists in nuanced ways, but all countries must articulate national contributions to reducing global emissions and must pursue mitigation measures.

The US complaint that emerging economies, including China and India, had no obligations under Kyoto has been resolved.

Indeed, the US complaint that emerging economies, including China and India, had no obligations under Kyoto has been resolved. Under the Paris Agreement, such countries are vowing to fill the void that the US withdrawal now creates. They are progressing on their pledges faster than expected and demonstrating that a shift to renewable energy can be economically beneficial. Several commentators have gone so far as to claim the US withdrawal from Paris may be more beneficial than harmful, clearing the way for these more ambitious states to lead.

Although the US administration may hope to sustain its influence over the climate negotiations, as it did after rejecting Kyoto, this tactic will not bear fruit. The Paris Agreement is the hard-won outcome of negotiations to decide on long-term action. It is a comprehensive treaty, and although the US is entitled to take part in the ongoing discussions, it will not be persuasive. Fears that states would desert the Paris Agreement without US participation are proving wrong, as heads of state from around the world make forthright statements about their enduring commitment. Officials in Canada, the EU, China and elsewhere have declared there will be no room for renegotiation.

In their effects on Canada, there is little similarity between the US abandonments of Paris and of Kyoto. The Chrétien government ratified Kyoto in 2002 and began planning to implement it, but the Harper government took the opposite direction, largely mirroring US policy, and eventually withdrew in 2011. In contrast, the Trudeau government has ratified the Paris Agreement and established a framework for a national carbon price, building on the leadership of Ontario, BC and Quebec. Canada’s positions on climate, human rights, trade, security and migration are diverging from those of the US. In the past few weeks, as Trump isolates the US from long-standing allies, Canada has forged a climate coalition with China and the EU. Nonetheless, Canadians are engaged in heated debates about the strength of our Paris pledge and recent pipeline approvals.

Perhaps the most notable sign that the world is on a different path this time around is the shift in attitudes and actions in the private sector and subnational jurisdictions. These advances are well publicized: the proliferation of renewable energy (and the impending demise of coal), disclosure of climate risks in corporate reporting, mass litigation compelling states to act, municipal partnerships to reduce emissions, subnational carbon pricing and more. Innovative approaches to address climate change are proliferating. Since controlling climate change was always going to require transformations across national boundaries, in jurisdictions down to the local level and by all public and private actors, some might say these burgeoning initiatives are what’s needed or what persuaded countries to reach the Paris Agreement in the first place.

At the same time, it would be overly optimistic to call even positive developments a “silver lining” to US recalcitrance. Mindsets have changed globally, as have the tools at our disposal, but the task of coordinating climate action across boundaries has not become simpler. In this context, Canada’s own record of fluctuating ambition is no longer an option, if it ever was.

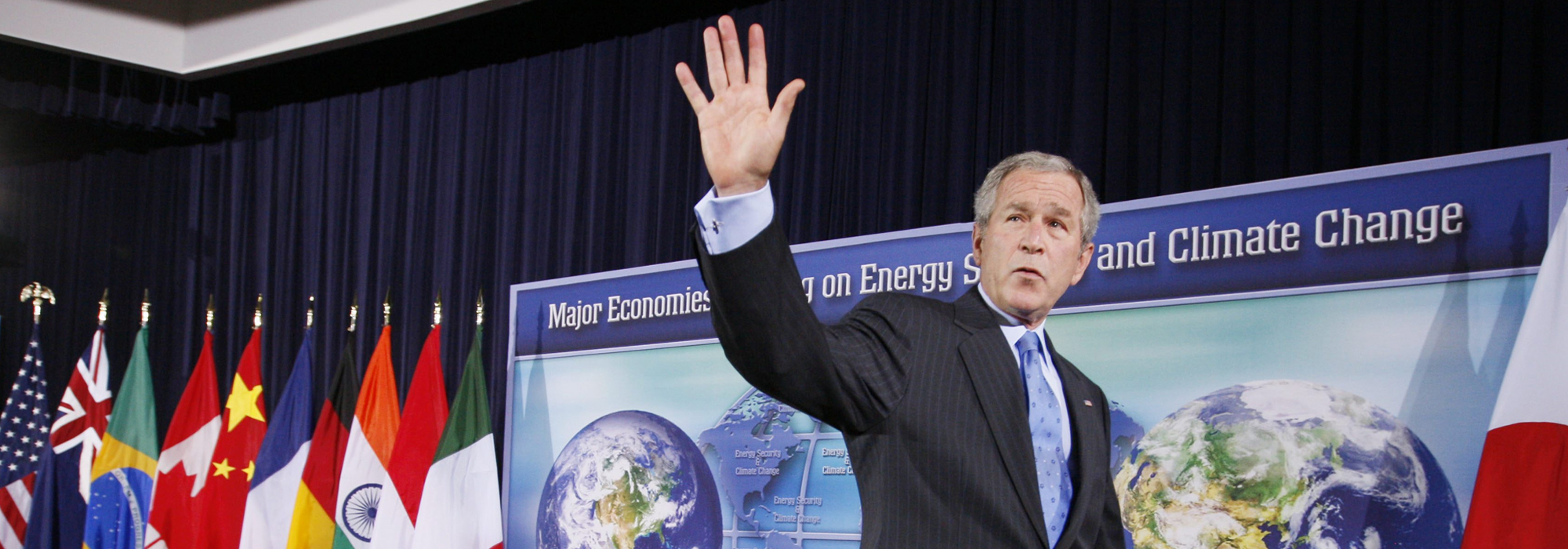

Photo: President Bush leaves the stage after speaking at a White House sponsored conference on Energy Security and Climate Change at the State Department in Washington, Friday, Sept. 28, 2007. (AP Photo/Charles Dharapak)

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.