Every May as red dresses and moose-hide pins appear, and families walk in memory of lost loved ones, a question hangs in the air. Why does the change they demand to end gender-based violence move so painfully slow? Statistics on abuse and murders of Indigenous women, girls and two-spirit people remain staggering.

The Assembly of First Nations tells us that Indigenous women comprise 4.3 per cent of the Canadian population but make up 16 per cent of homicide victims and 11 per cent of missing women. Families and advocacy groups estimate that over 4,000 women and girls have disappeared or been killed in the last 30 years. The brutal murders of Pamela George, Marcedes Myran and Tina Fontaine are just a few examples that highlight continued racism and indifference toward Indigenous women in our country.

This crisis has led to a sometimes shouted, sometimes unspoken rage among Indigenous Peoples.

It is present in Facebook posts as families plead for information about lost loved ones. It is seen in my own community, Elizabeth Métis Settlement in Alberta, where we buried four women in the span of two weeks in May. It could be heard in the voice of Morgan Harris’s daughter, Cambria Harris, as she pleaded with the Manitoba government to search for her mother’s body. It underscores the grief in a father’s request for an honour song for his daughter Ashlee Shingoose (Mashkode Bizhik’’ikwe).

Historical context of violence

To understand why this violence persists we need to examine the impact of colonialism and unravel layers of legislation, policies and institutional silence that have oppressed Indigenous women. Violence against Indigenous women, girls, two-spirit and trans people is directly connected to the colonial disruption of Indigenous social structures, kinship dynamics and gender roles.

Historically, First Nations, Metis and Inuit women held important legal, governmental, economic and social roles in their communities. This threatened the patriarchal ideologies of European settlers who saw men as superior to women.

British and French settlers were able to enforce gender and racial hierarchy by placing more worth on Indigenous men’s existence and rights, for example, by restricting leadership roles to First Nations males. Indigenous writer and advocate Lee Maracle called this the “denial of native womanhood” through a racist and sexist narrative that Indigenous women do not deserve dignity or protection.

Legislative oppression

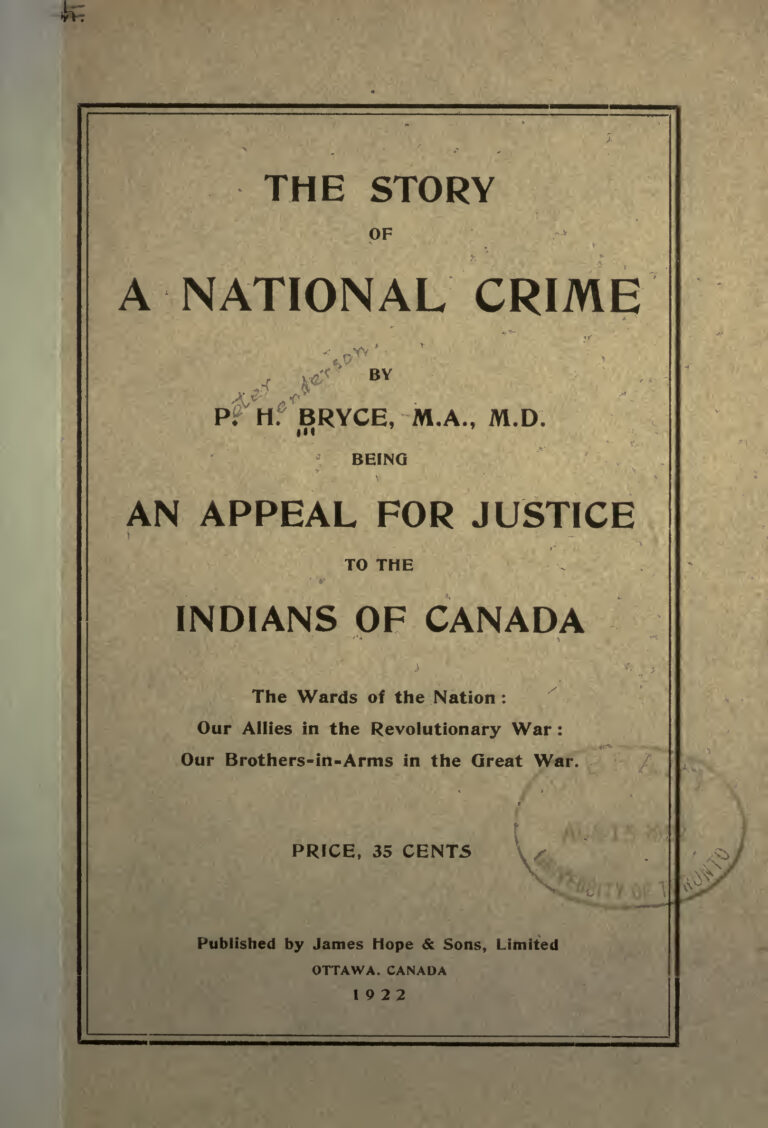

These sexist ideological views were enforced repeatedly through policies and legislation, most notably the federal Indian Act and sexual-sterilization acts in two provinces.

The former, enacted in 1876, institutionalized gender-based discrimination against First Nations women by barring them from elected positions and making their status conditional on their husbands’. They could not possess land or marital property unless they were widows, and, even then, the deceased husband’s property typically went to their children.

A change to the legislation in 1884 allowed a woman to receive her husband’s property, but only with an Indian agent’s consent. The agent had to confirm the wife was of “good moral character.” This choice of words reflected the Crown’s patriarchal belief that women’s value was linked to Christian virtues of purity, obedience and submissiveness.

Why are the deaths of Indigenous women and girls ungrievable?

What #JusticeforJoyce should mean for policy-makers

Excising racism from health care requires Indigenous collaboration

Perhaps most shocking was the illegitimate-female-child rule. It decreed that if a First Nations man with status had a child out of wedlock, a son could register to have status, but a daughter could not. Similarly, if a husband lost his status, his wife and children would automatically lose theirs as well.

These laws meant that First Nations women were excluded from their communities, cultures, languages and traditions, which created a rift still felt today.

Indigenous women also faced forced and coerced sterilization. This disturbing and violent practice was fuelled by eugenics principles that removed reproductive choice and led to Alberta (1928) and British Columbia (1933) each passing a Sexual Sterilization Act to support it. The acts were not repealed until the 1970s.

Professor Karen Stote, who specializes in reproductive justice, genocide and eugenics, has estimated that between 1971 and 1974, over 700 patients were sterilized at Indian hospitals and federally operated hospitals. Most were Indigenous women.

For almost a century, Indigenous women were subject to exclusion, dispossession and alterations to their bodies because of these laws. Such continuous and repeated behaviour led to a collective rage that has been passed down by Indigenous women who have been silenced and dismissed.

Indigenous resistance and legal challenges

But alongside intergenerational rage comes intergenerational grit.

Many women have stood up against oppression and advocated for the rights of Indigenous women. Nellie Carlson and Yvonne Bedard, for example, challenged sexist restrictions in the Indian Act but were overruled by courts, which upheld the “marrying out” rule. Despite their legal defeats, Carlson and Bedard helped create national momentum in the fight for Indigenous women’s rights and freedoms in Canada.

In 1981, Sandra Lovelace, who would later be appointed to the Senate, was denied the ability to return to her reserve after marrying a non-First Nations man. She took her case to the United Nations Human Rights Committee, which found Canada to have breached the International Covenant on Civil Rights. This caused even more pressure for the Indian Act to be amended.

The marrying-out rule was repealed after the Canadian Human Rights Act was introduced in 1985. That same year the Indian Act was amended to restore status to more than 100,000 First Nations women.

In 2019, the federal government created a working group to examine forced sterilization of Indigenous women. Some cases have again come to attention in recent years, including one involving an Inuk woman. Senator Yvonne Boyer plans to reintroduce a bill in Parliament that would make forced sterilization punishable under the Criminal Code.

Modern manifestations of violence

The ongoing consequences of systemic racism and sexism are still evident in the ways Indigenous women are treated.

For example, families estimate that over 40 Indigenous women have been murdered or disappeared in northern B.C. along a stretch of road called the Highway of Tears, yet many cases have never been solved. A report by Human Rights Watch discussed the systemic discrimination facing Indigenous women in the province and specifically noted the problematic behaviour of the RCMP toward them.

In Manitoba, a serial killer was convicted last year of murdering four Indigenous women: the aforementioned Myran, Harris and Shingoose and also Rebecca Contois. Some remains were found in garbage bins near his apartment and others were believed to be at two landfill sites. Yet the previous provincial government refused to search the area. Wab Kinew reversed that decision when he became premier and after countless requests from victims’ families.

The path to collective healing

Change is happening. The federal government is working with the provinces and territories on a Red Dress Alert pilot project to notify the RCMP when Indigenous Peoples disappear. Earlier this year, more than 300,000 Canadians supported the Moose Hide Campaign aimed at engaging men and boys to help end violence toward women.

But the pace of change does not reflect the urgency of the crisis. True healing can only start when Canada acknowledges its role in creating a wound caused by generations of inaction. The National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls laid out a clear roadmap for Canada: Implement the inquiry’s calls for justice, honour Indigenous self-determination and address the systemic causes for gender-based violence.

It remains to be seen when Canada will respond so the question “why?” no longer needs to be asked.