While we are among the most highly educated countries in the world, many of our workers lag behind their peers in international assessments of cognitive skills, like literacy and numeracy. In the most recent assessment conducted by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Canadian adults aged 16 to 64 ranked in the middle of the class — at the international average score in literacy and below the average score in numeracy.

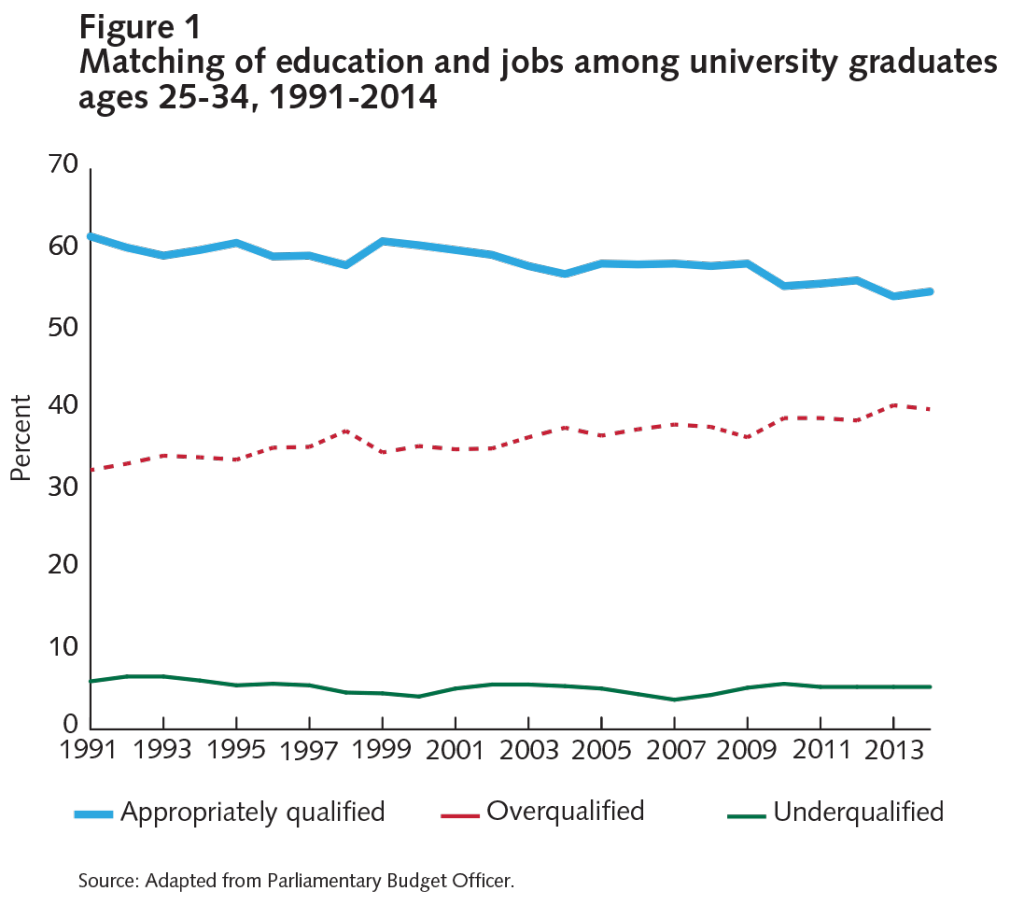

But research published in November 2015 by the federal Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) finds a rising incidence of overqualification among recent university graduates (figure 1). Taken together, the two reports suggest that despite a substantial increase in educational attainment at the top end, the skill distribution of jobs has not kept pace.

In a world where the competition for human capital is global, these results raise some important questions about whether our success as a country of credentials has actually given us the underlying skills needed to remain competitive.

Unfortunately, this is not the conversation being conducted in the policy community today.

Because credentials are an easy — and often the only — signal to employers of a worker’s technical capabilities, many policy analysts spend disproportionate time thinking about the optimal level and mix of educational attainment. The fact that the recent PBO report prompted some in the media to question the relative value of college versus university education is further confirmation that we are thinking about this problem in the wrong way.

College and university education aren’t necessarily interchangeable, so the notion that one is better than the other relies on a false dichotomy. In thinking about the match between jobs and skills, the issue is whether our instructional systems produce the right set of skills that are in demand. Those skills can come from a variety of educational paths.

While we may reasonably assume that higher levels of education produce higher orders of skills, we don’t really know. Without knowing what specific skills are actually taught within these programs, it is hard to assess from a credential how effective a worker will be in performing the specific tasks related to a job. We can hope that people with MAs in economics have decent econometric skills, but, as the Bank of Canada has found, the degree won’t tell us whether they can actually write or communicate in a way that critically assesses the policy issues at hand.

This is why literacy and numeracy assessments, although at times time-consuming and cumbersome to implement, provide important insights into the application of cognitive skills by workers. Embedded within these assessments are a number of activities that demonstrate in real-world application whether workers can apply their knowledge and formal education to the tasks at hand. And yet our policy discourse regularly ignores the evidence from literacy and numeracy assessments among adults and even attempts to minimize its implications.

Since the release of the last round of adult of literacy and numeracy assessments by the OECD, a variety of policy analysts, educators and researchers have argued that Canada needn’t worry. The reason, they say, is that a simple comparison of average scores across countries doesn’t properly account for Canada’s disproportionately large cohort of allophone first-generation immigrants, many of whom score lower on literacy and numeracy surveys, in part because of significant language barriers. As noted in a recent report published by the C.D. Howe Institute: “Canada places above the international average when the literacy scores of its immigrant and non-immigrant populations are considered separately, but falls to only average when the scores of both groups are combined.”

Composition is an important factor to keep in mind, but only insofar as it helps us understand how to compare Canada with other countries in a given assessment period. The more important questions to ask — and those which have yet to really take hold in the policy debate — ought to be these:

- How has our overall performance changed over time?

- Are specific cohorts doing better or worse now than they were 10 or 20 years ago?

- How have the skills of adults changed as they have aged and moved from learning into work?

The answers to these questions hold a variety of important implications for Canada, from how we apply pedagogy and design instructional systems to how we think about the application of skills in the context of work and how society supports the acquisition and development of skills over the course of life.

Though formally measured on the basis of either literacy or numeracy, cognitive skills bring together a bundle of nine component skill sets, collectively known as “essential skills.” These include proficiency related to language, reading prose, document use, numeracy, working in teams, problem solving and using digital technology. These skills are important because a variety of research demonstrates that they explain a large amount of an individual’s — and a society’s — economic potential.

A small but growing body of research suggests that Canada is doing progressively worse over time in developing and using cognitive skills. Here, we augment this work with new data from the 2011 Survey of Adult Skills conducted by the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) in order to draw out a comprehensive picture of how Canada’s skill performance is changing.

Beginning in 1994 with the International Adult Literacy Survey (IALS), Canada has been a pioneer in developing and conducting international assessments, a process that has grown over time to include nearly all OECD countries. The goal of the assessment program was to profile the distributions of skill among OECD countries; to document the impact of skill on a range of individual and macro economic, educational and social outcomes; and, through comparison of results over time, to shed light on the processes of skill gain and loss in adult populations.

To address the concerns of those who argue that Canada’s performance is potentially skewed by important compositional factors, we break up our analysis into several parts, looking in particular at how the distribution of scores has changed within different population subgroups. Furthermore, to avoid potentially misleading statistical effects, we focus on how the overall distribution of scores has changed over time, at the bottom, middle and top. This helps us go much deeper than the conventional analysis that is restricted to average scores.

We focus specifically on tests of document and prose literacy since these assessment methods are reasonably consistent across time. In the tests, respondents are assessed on a variety of questions, the results of which provide a formal score that is scaled between 0 and 500 points.

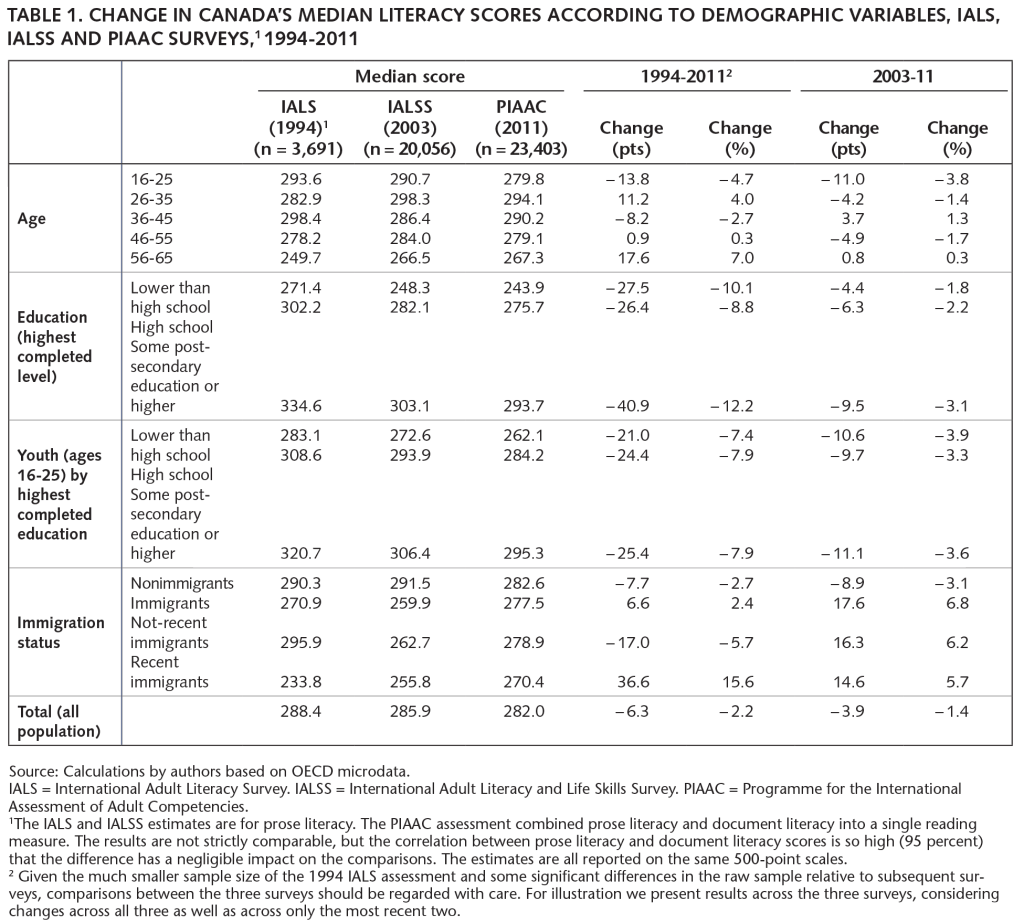

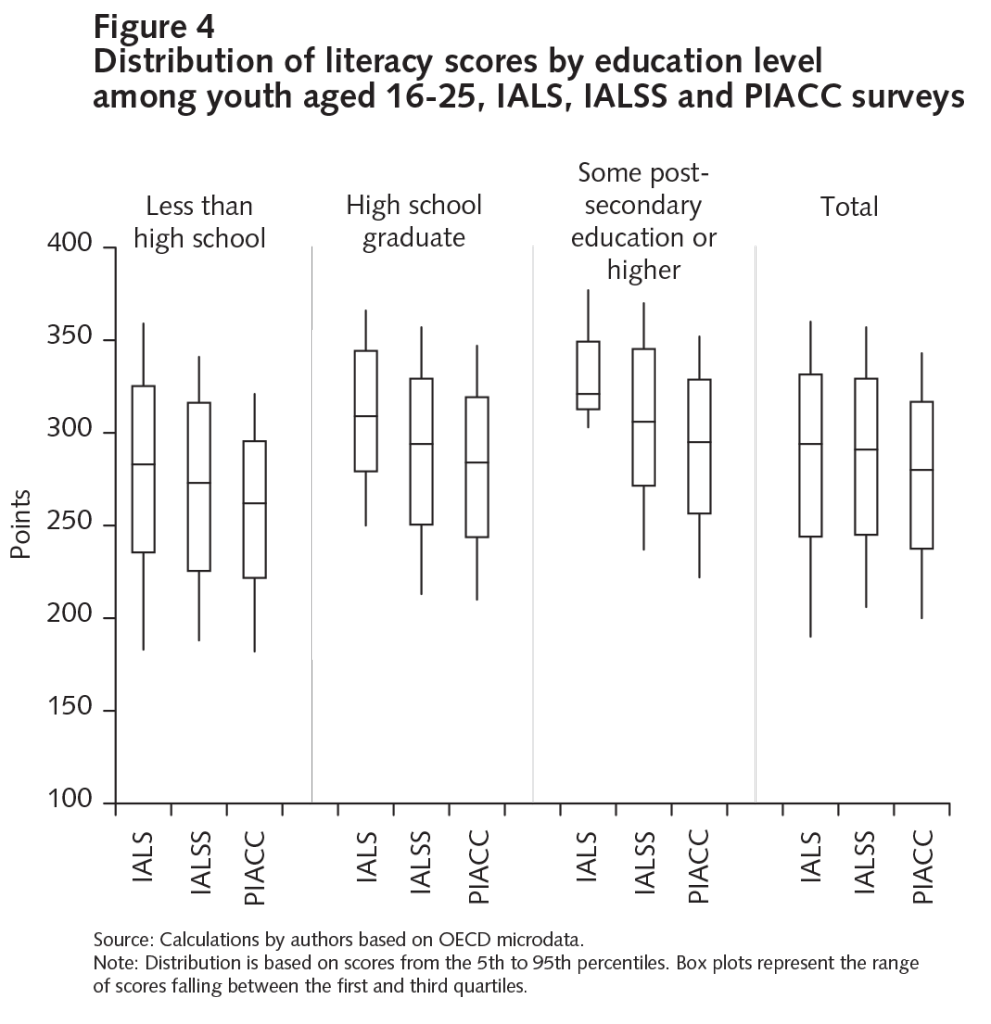

The story to draw from the data is, on balance, somewhat worrying. Of the 15 population groups reported in table 1, 10 experienced a decline in median scores over the course of successive assessments — in some cases by nontrivial amounts.

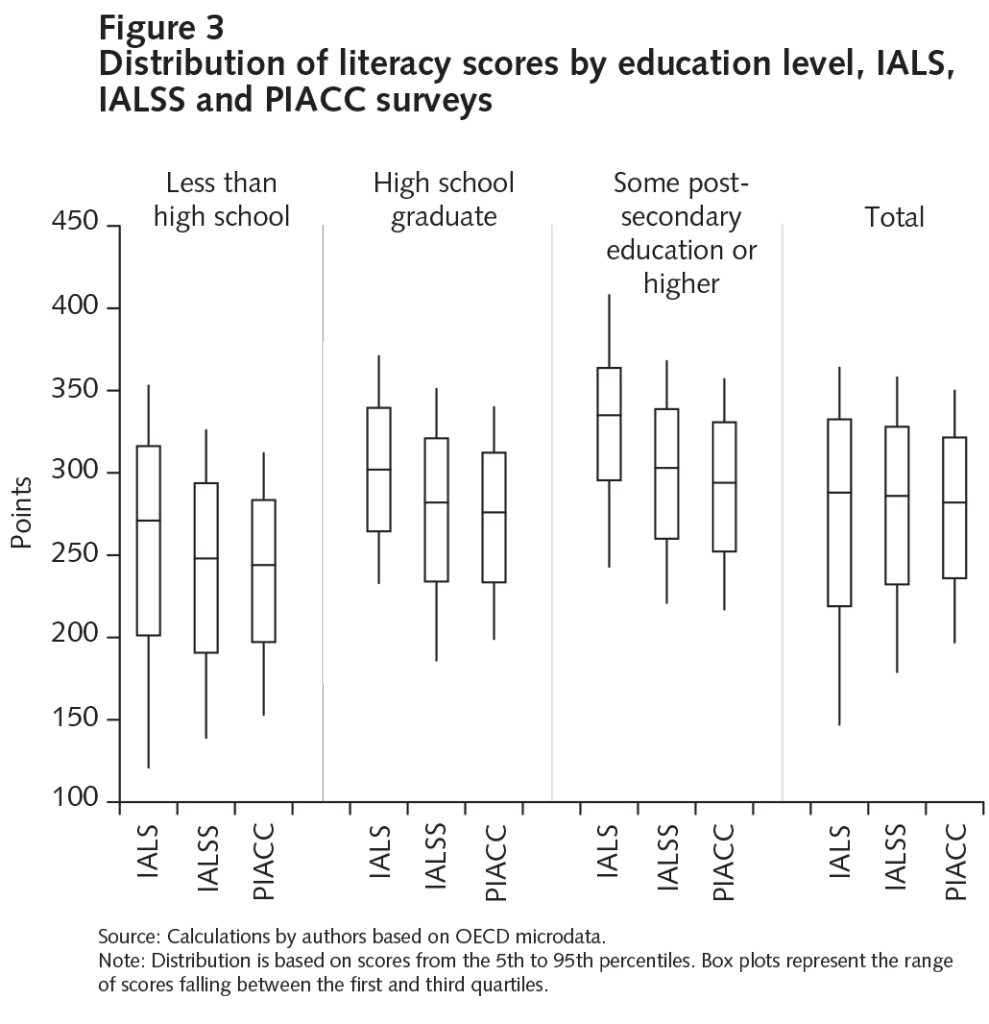

To put these numbers into context, there are five levels of literacy proficiency, from level 1, starting at 176 points, up to level 5, which encompasses scores of 376 points or higher. A change in score of about 50 points shifts a person from one level of literacy proficiency to another. In 1994, the median adult possessing at least some completed post-secondary education was proficient at level 4 literacy; by 2011, the median adult had dropped to a score within the level 3 range.

Because of significant differences in the samples drawn between the first assessment in 1994 and the subsequent ones conducted in 2003 and 2011, some may not wish to directly compare the results across the three periods. With the 1994 survey excluded, the decline in scores between the 2003 and 2011 assessments is less pronounced but still noteworthy, particularly among youth, where higher levels of education were clearly no insurance against skill loss.

While there are some differences within groups depending on which survey years are included in the comparison, only recent immigrants and, to a lesser extent, older workers experienced a noticeable and persistent improvement in literacy performance.

That recent immigrants have done better over time flies in the face of the conventional wisdom that immigrants continue to pull down Canada’s overall performance in these assessments. Respondents who at the time of assessment had just recently immigrated from abroad had a median score 37 points higher in 2011 compared with their cohort in 1994 and 15 points higher compared with those surveyed in 2003. These were among the biggest changes across all groups in the data. By contrast, the median Canadian-born adult scored approximately 8 and 9 points lower in 2011 than in 1994 and 2003 respectively, drops that are likely not statistically significant. As concerning as the drop in median scores would seem to be, it is better to think of this shift as a compression in scores rather than a uniform decline in performance.

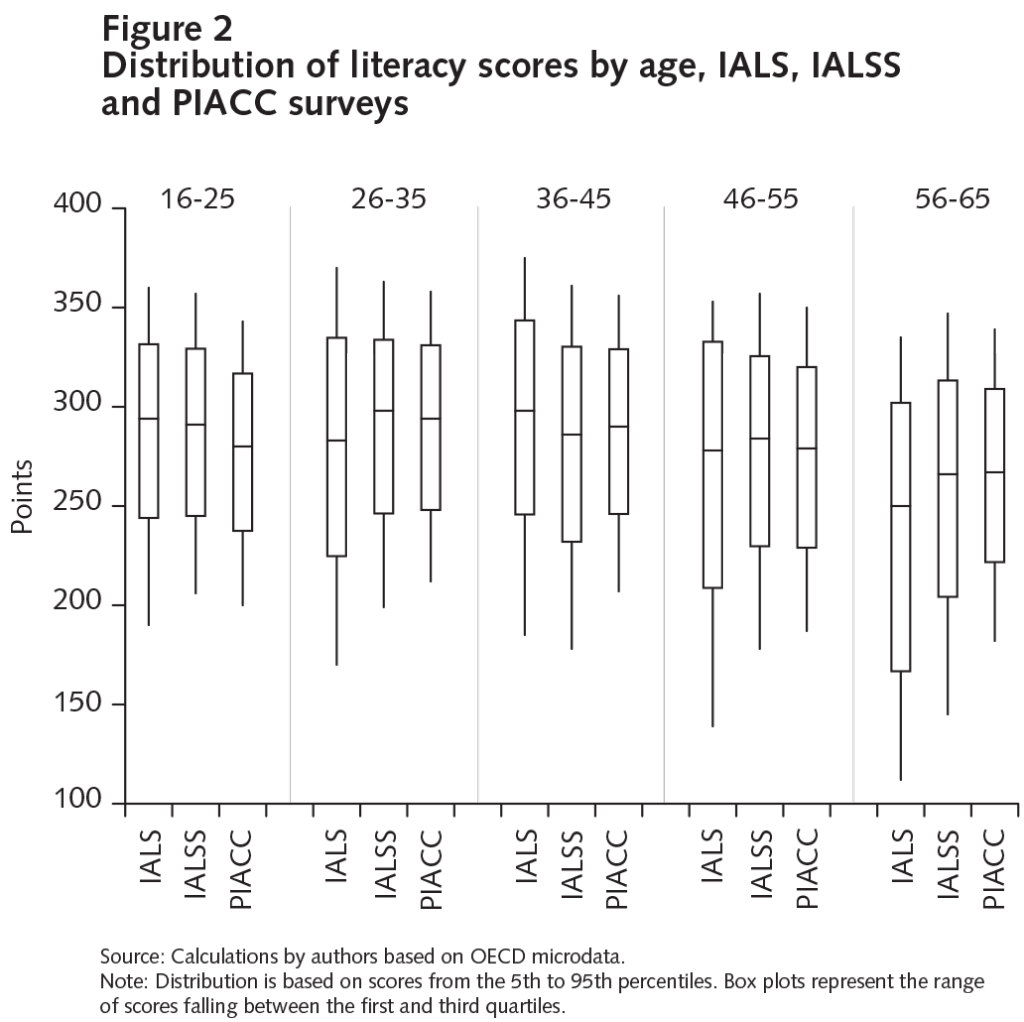

Looking at the distribution of scores across population groups (figures 2-4), it is obvious that important changes have occurred in two directions: the lowest-performing respondents have improved considerably, while the highest-skilled have fared progressively worse. Overall, this produced the negative effect of lower median performance, while at the same time the difference between the 5th and 95th percentiles has shrunk quite consistently.

Among the population as a whole, median scores declined by an insignificant 6 points between 2003 and 2011. However, within these results, the difference between those scoring at the 5th and 95th percentiles dropped by 26 points – equal to half a literacy level. This was mostly the result of improvement among those at the bottom and a very slight decline among those at the top.

An even more significant trend can be seen among older adults, aged 56 to 65. In 2003, the difference between those scoring at the 5th and 95th percentiles was equal to approximately 202 points. In 2011, this difference shrank to 157 points, essentially closing the distance between the top and the lowest performers by one entire literacy level. Those in the 5th percentile rose from 145 to 182 points, while the 95th percentile fell from 347 to 339 points over the period. The median score among this group of adults was essentially unchanged.

That we are doing somewhat better in providing a basic floor of literacy skills for some is an important development not to be overlooked. However, amid this improving picture at the bottom of the skill distribution, our overall performance is still middling.

Successive cohorts of Canadian youth and — of particular concern — those with higher levels of education are displaying cognitive skills that are adequate but modestly less proficient. While this is not a moment to sound a widespread alarm, the marginal declines in performance we are beginning to see among certain segments of the population should cause us to reflect carefully on how Canada is positioned as a human capital economy. As a country that faces significant challenges of productivity and innovation, we need to better understand what is driving this mediocre performance.

To be clear, this is about more than just our educational institutions. The development and application of cognitive skills comes from a variety of sources, including what we learn, how we engage in things like reading and interpersonal activities, and how our skills are drawn upon in the workplace. One mistake would be to say that this performance is simply the fault of teachers and pedagogy. It is not.

Employers need to be actively engaged in this discussion. Compared with some of our international peers, firms in Canada do not have a particularly strong training culture and are not as aggressive in thinking about how, at the level of specific jobs, we can use people and technology to increase the skill content of work. Firms have become used to governments —and, to a lesser extent, learners — financing the human capital investments needed to support our economy.

Before dwelling on the specific policy actions that may be required, we need to have an open and honest debate about what’s happening with skills, in terms of both the supply and the demand for them. Given the significant investments in skills training promised by the new federal government, now more than ever, we need to get a handle on why we are falling behind in cognitive skills even as we become more “educated.” We have been avoiding these hard questions for too long.