For most of Canada’s history, a broad consensus existed on the principles that should govern criminal justice reform, though there were always disagreements about details. The consensus is evident through statements from cabinet ministers, government reports, royal commission reports and criminal justice experts. This shared vision ended in 2006. In this essay we suggest that the next government might initiate a renewal of the criminal justice system. It could readily identify broad principles that would raise little controversy. Then, rather than making piecemeal changes, it could review large areas of the criminal justice system, instituting changes that reflect broad integrated knowledge of current problems, long-standing Canadian values and empirical knowledge. Such an approach requires only the will to create a fair, efficient and effective criminal justice system.

The pre-2006 consensus is illustrated by this quiz. For each statement, try to guess the speaker’s party, and roughly when the statement was made. But be warned, it’s hard, because the consensus was so widely shared and long-lasting. The core of that consensus consisted of four pillars:

Social conditions matter. Before 2006, involvement in crime was understood as not simply about choices that individuals make. Rather, it was also a product of the social conditions in which people live. Quotations 1-6 illustrate this belief. Governments struggled with criminal justice issues but understood that solutions to crime largely lay elsewhere. In fact, the long-term protection of society was seen as best served through crime prevention.

Harsh punishments do not reduce crime. An impressive quantity of research demonstrates that governments cannot measurably affect crime rates by increasing punishments. Previous governments understood this reality (quotations 7-8) and policy-makers did not expect prisons to reduce crime (quotations 9-14). Indeed, the emphasis was on attempting to ensure that prisoners were not released in worse shape than when they entered (quotations 15-18). Unsurprisingly, restraint in the use of imprisonment was uncontroversial. When the Liberal government released a policy document in 1982 promoting this principle, it was criticized by a Globe and Mail columnist as repeating mere “motherhood” statements. The Conservatives reprinted the Liberal policy document in 1989, making one change: the preface with Jean Chrétien’s signature (as justice minister) disappeared.

Development of criminal justice policies should be informed by expert knowledge. Ministers and governments had priorities, and changes were typically a result of discussions about priorities and policies. Details of public policies were largely left to professional, experienced experts under the direction of their political masters. Broad consultation was required. Evidence mattered. Consensus across stakeholders (federal and provincial as well as public and private) was sought. As a result, development of criminal justice policies would often be conducted by royal commissions, government-appointed committees or parliamentary committees, and they took time to ensure a comprehensive examination of the issues. With such a broad-based approach, criminal justice policy was seldom the source of partisan divide, and work begun under one government was often completed by another. Notably, some of the ideas in the 1990 Conservative policy documents on sentencing and corrections — leading to, among other things, the Corrections and Conditional Release Act — can be traced to studies initiated by Liberal governments. The Conservatives didn’t hesitate to say so. “Although the recommendations of these studies sometimes diverged,” wrote the Conservative justice minister and solicitor general in 1990, “there has been a large measure of consensus on needed changes that the government can draw on. While the options proposed in this document are the responsibility of the government, it is important to recognize the significant debt the next step in criminal justice reform owes to these preparatory analyses.” That statement wasn’t controversial.

An impressive quantity of research demonstrates that governments cannot measurably affect crime rates by increasing punishments.

Changes in the criminal law should address real problems. Politics has always been a concern in the development of criminal justice policies — as it should be in a democracy — but under the old consensus, politics only occasionally was the predominant concern. For example, in 1986 the Conservative government introduced legislation to block the release of certain offenders after they had served two-thirds of their sentences. Although plainly counterproductive because it means that those deemed most likely to commit serious violent crimes are released without any supervision when their sentence expires, this legislation was prompted by a high-profile murder by someone on “early” release. The political need to be seen to be doing something trumped good policy.

Similarly, the Liberal government introduced mandatory minimum sentences for some gun crimes in 1995 to soften opposition to its proposed long-gun registry. Although it understood that harsher sanctions do not reduce criminal activity, political need (to gain support for the Bill) outweighed good policy. But these examples stand out because they were relatively rare. Most criminal justice policy changes had obvious policy goals. Policy changes were even made when a political analysis would suggest there was political risk and nothing to be gained. This happened in 1982 and again in 2002, when major reforms of youth justice were legislated by Liberal governments. And it happened in 1992, when a Progressive Conservative government passed the Corrections and Conditional Release Act, which governs imprisonment. For the most part, it was understood that “good -government” included expending effort on criminal justice issues that weren’t necessarily vote-getters.

When Stephen Harper’s government assumed power, the old consensus crumbled. In its place, a new vision of the role of the criminal justice system in Canadian society was adopted that defied the basic elements on which consensus had rested for over a century.

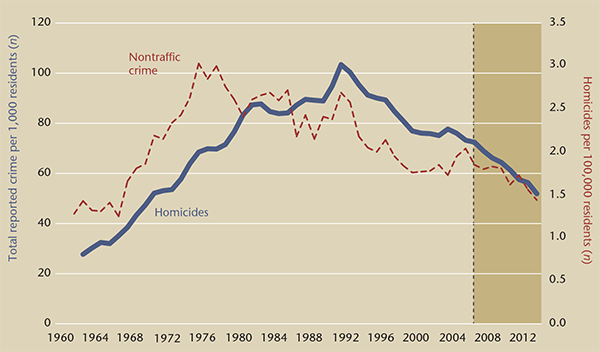

Crime can be solved through the criminal justice system. While crime prevention is occasionally mentioned, current criminal justice policies are almost exclusively focused on harsh punishment as the primary vehicle to control crime. Restraint in the use of the criminal law or imprisonment has disappeared. While the Harper government has generally avoided stating the rationale underlying its choice of crime policy domains, it has occasionally expressed a clear belief in the efficacy of punishment. As Harper himself said in 2014, “We said ‘do the crime, do the time.’ We have said that through numerous pieces of legislation. We are enforcing that. And on our watch the crime rate is finally moving in the right direction, the crime rate is finally moving down in this country.”

As figure 1 suggests, the Prime Minister’s statement took advantage of a pre-existing trend, and the continued drop in crime rates had nothing to do with his policies. The beginning of his government (2005) is marked with a vertical line.

Crime is exclusively a matter of individual choice. The Harper policies involve much more than increased penalties. Rather, they represent an explicit attempt to create divisions among Canadians: offenders are not the product of social circumstances but are inherently bad people who should be permanently distinguished from law-abiding citizens. As reported in the Toronto Star in February 2011, referring to the 421 percent increase in the cost of applying for a pardon, Harper’s public safety minister simply explained that “ordinary Canadians should not be having to foot the bill for a criminal asking for a pardon.” This statement not only neatly divides Canadians into two distinct groups but also ignores the Public Safety Canada data that suggest that 21.2 percent of Canadian males and 3.9 percent of females over age 12 have criminal records. Over 95 percent of those receiving pardons never reoffend. Gone is any real attempt to reintegrate offenders or any belief in the practice. Being an “offender” is seemingly a permanent identity. Not surprisingly, pardons are no longer available for many offences, even some that carry relatively low maximum (18-month) sentences.

Similarly, the normative assertion that “they” have forfeited the claim to have their interests or human rights taken into account also appears to be increasingly considered an appropriate consequence of wrongful behaviour. One need only recall Harper’s 2006 election promise to work toward a constitutional amendment to take the vote away from federal prisoners.

Further, the punitive effect of legislation on disadvantaged people is either ignored or desired. A bill introduced in March 2015 would restrict some offenders serving penitentiary sentences for sexual or violent offences to six months of supervised “statutory release” rather than the current one-third of the sentence. The government’s own data demonstrate that 32 percent of non-Aboriginal women but 54 percent of Aboriginal women are at risk of serving more time in penitentiary under this proposal. For men, 46 percent of non-Aboriginal prisoners might serve longer sentences, as compared with 61 percent of Aboriginal offenders. So this bill would increase the already disproportionate imprisonment of Aboriginal people in Canada: Aboriginal people constitute about 3 to 4 percent of the population of Canada but 23 percent of the men and 33 percent of the women in Canada’s penitentiaries.

The government would have known about the Bill’s disproportionate impact on Aboriginal people. The data are publicly available in government reports and demonstrate similar disproportionate effects of current policies on Aboriginal people. In this context, it is little wonder that Harper sees the large number of missing and murdered Aboriginal women as a crime problem, not a sociological phenomenon, and he is not — unlike his predecessors — interested in looking for systemic solutions. Much has changed, it seems, since the 1968 Conservative platform of Robert Stanfield, which stated that “one of the greatest blots on Canada’s reputation for fairness and equity is the condition of [Canada’s Aboriginal people]… It is a problem that should touch the conscience of all Canadians.”

Crime legislation is developed largely by politicians, without advice from those knowledgeable in criminal justice policy. It is not coincidental that the recourse to government or government appointed commissions and committees — with their emphasis on extensive consultation, evidence-based recommendations and broad consensus across stakeholders — has all but dried up. Other than one discredited 2007 report on federal imprisonment, there have been no broad policy documents. Meaningful debate and broad examination of legislative bills have been severely truncated. Notably, many of the criminal justice initiatives have been passed without serious discussion of costs. Rather than thoroughly reviewing broad policy fields and introducing comprehensive reforms, the current government constantly fiddles and tweaks.

It is hard to believe that anyone is fully happy with Canada’s sentencing system.

The government’s signature justice reform — the creation of mandatory minimum sentences — follows this pattern. If the government believes, in fact, that sentences in general are too lenient, it could review sentencing generally and consider broad reforms that would accomplish its policy goals. But it has declined to do so. Instead, it has introduced one mandatory minimum after another, often in response to headlines somewhere in Canada, with no apparent consideration of the cumulative effect of these changes on the coherence of sentencing or the operation of the courts. Nor, for that matter, has the government taken into account the extensive research demonstrating the ineffectiveness of mandatory minimum sanctions in reducing crime.

Crime policy has become increasingly politicized. So far, the Harper government has introduced 90 criminal justice bills, including two multipart “omnibus” bills. The sheer number has ensured that the underlying message that offenders are inherently bad people is heard repeatedly. Hence, one of the most obvious manifestations of the centrality of political calculation is the government’s piecemeal approach to reform. Sometimes changes are consequential but almost always they are focused on a few specific matters — some of which do not appear (empirically) to even be problems. Consider the changes that the government has introduced to parole and other forms of release of federal prisoners into the community:

- The government made general changes to attempt to restrict parole. Yet, evidence demonstrates that if full parole were completely abolished for those serving ordinary sentences, Canada’s imprisonment rate would increase by only 2.7 percent.

- It abolished the “faint hope” clause whereby those serving life sentences could have their parole ineligibility period reduced by a jury. About six people a year received shorter parole ineligibility periods under this law.

- A form of presumptive parole was abolished.

- Consecutive parole ineligibility periods were introduced for multiple murderers.

- Legislation permitting sentences of “life in prison without parole” was introduced.

- Legislation restricting presumptive release of prisoners at the two-thirds point in their sentences was introduced.

Notably, these initiatives were contained in six separate bills over a six-year period, so Parliament had no opportunity to examine conditional release of prisoners as a whole. But six bills meant six times as many opportunities to communicate the government’s message — that it is on the side of good people and is making life unpleasant for bad people — than it would have had if only one comprehensive bill had been introduced.

Even more illustrative is the plethora of reforms that can only be described as minor, trivial or redundant. In 2006, the Harper government introduced legislation increasing the (Liberal-imposed) mandatory minimum sentences for first-time violent offences with a handgun or prohibited weapon (but not a shotgun or rifle) from four to five years. The suggestion — it seems — is that people will be deterred by a possible five-year sentence but not a four-year sentence.

In 2014 the government introduced the Justice for Animals in Service Act (Quanto’s Law), named for a police dog killed in service. It would create a new offence of killing or maiming a police or military animal, notwithstanding the fact that comparable laws already exist. The announcement was made by the Prime Minister himself, with his wife and cabinet minister Rona Ambrose also in attendance. Similarly, a new aggravating factor in sentencing was created in 2012 with the Protecting Canada’s Seniors Act, which requires consideration of “evidence that the offence had a significant impact on the victim, considering their age and other personal circumstances, including their health and financial situation.” Those 24 words constitute the entire substance of the bill. We doubt that there is a judge anywhere who wasn’t already considering the vulnerability of victims. The government suggested that “this legislation would further support our Government’s common front to combat elder abuse in all forms…The interests of law-abiding citizens should always be placed ahead of those of criminals.” While arguably a means of attracting targeted voters, this approach ignores the need for comprehensive, thoughtful bills.

There is little doubt that fundamental differences exist between the Harper government’s vision for the criminal justice system and the one rooted in the consensus that preceded it. Bridging these divides seems unlikely. However, we would argue that a new agenda for Canadian criminal justice policy is still well within our reach.

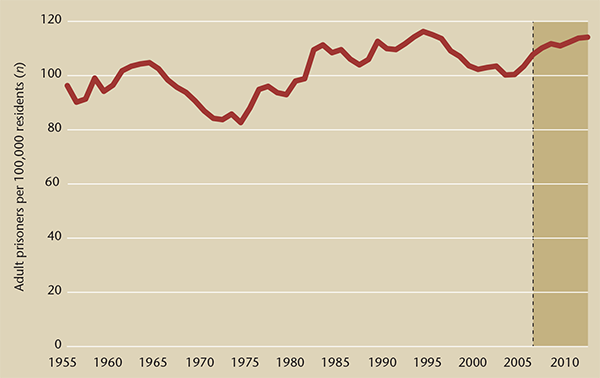

The next government need not panic. Notwithstanding the many uncoordinated changes since 2006, and contrary to the worst fears of critics, incarceration rates have not increased dramatically (see figure 2).

If we look at the evidence presented in figure 1, Canada has neither a crime crisis nor, so far, an imprisonment crisis. Notwithstanding recent divisive approaches to criminal justice policy, we are confident that a few basic principles that almost certainly are consistent with the values of most Canadians could form the basis for systematic reform of the criminal justice system.

1) Prosecutions should be effective, fair and efficient. It is hard to believe that this suggestion could be controversial. However, there is evidence that mandatory minimum sentences disrupt the prosecution process. Substantial numbers of people charged with criminal offences who are in jeopardy of losing their liberty or livelihood cannot afford lawyers. People wait months, if not years, to have their cases heard. Decisions on pretrial release that used to be concluded in one hearing now take days.

2) The criminal justice system’s response to wrongdoing — and sentences in particular — should be proportional to the seriousness of the offence.

3) Governments have a responsibility to focus resources on prevention. Medical interventions early in life (e.g., visits by prenatal public health nurses to at-risk families) improve a child’s physical health and reduce later criminal behaviour. School policies and practices can be shaped to reduce violence. We can invest in preventing crime or we can invest in imprisoning more people. It costs more to imprison one person for a year than it does to hire one teacher or one police officer or one visiting public health nurse.

It is hard to imagine that many people would argue against effective prosecution, proportional response to crime and a serious focus on prevention. Within this context, we would suggest that rather than tinkering with individual sections of laws, Canada should look broadly at our criminal justice system, guided by our history and by evidence. A government could examine areas such as the following:

- Bail and the pre-sentence custody problem. Of all prisoners in Canada, 35 percent are awaiting trial (that is 55 percent of all provincial prisoners). Using existing research, thoughtful cooperation between the provinces and the federal government could address this problem effectively.

- Court processing and court delay. Accused people, witnesses, police officers and court personnel waste an enormous amount of time and money with unproductive court appearances. Even simple cases often take months to be completed. Ten years ago, the federal department of justice worked with its provincial counterparts on this issue. There is a substantial amount known about the problem, which would point to effective solutions.

- It is hard to believe that anyone is fully happy with Canada’s sentencing system. The 1996 sentencing provisions constituted a good first step. However, more steps are needed. Canada could learn from the experiences in other countries on how sentencing decisions might best be structured.

- In 1989, the Correctional Service of Canada created a mission statement that included two “core values,” which appear to have been forgotten: “We respect the dignity of individuals, the rights of all members of society, and the potential for human growth and development,” and “We recognize that the offender has the potential to live as a law-abiding citizen.” In the past five years, an average of 5,116 recently sentenced prisoners entered Canada’s penitentiaries. On average, 53 prisoners per year die from all causes in federal penitentiaries. The rest return to the community. It is in everyone’s interest to ensure their effective reintegration. Those “lost” core values might constitute a starting point.

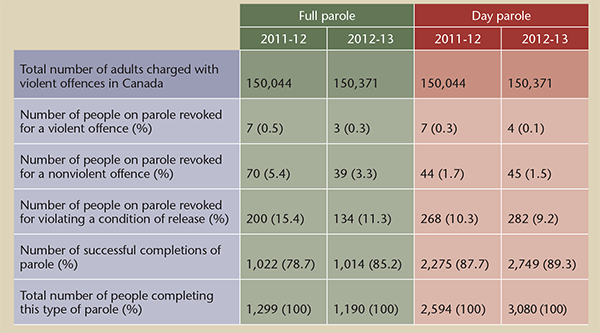

- Parole and other forms of release from prison. Parole and related issues have been the target of piecemeal legislation. A thoughtful review of Canadian practices might help us learn from our successes. Those released on parole from Canada’s penitentiaries are responsible for almost no crime (table 1). Of the roughly 150,000 adults charged in Canada with a violent offence, very few (7 in 2012-13; 14 in 2011-12) were on some form of parole. Unsuccessful paroles relate largely to violations of conditions of release, not reoffending.

These areas are examples of what any government that is interested in creating a fair, efficient and effective criminal justice system might do. None is easy. Achieving a consensus will be a challenge. But in the past 50 years, we have accumulated substantial knowledge on the operation of the criminal justice system. A government motivated to make improvements could show leadership and, in cooperation with the provinces, move Canada’s criminal justice system in a direction of which most Canadians would approve.

Photo: Shutterstock