As Canada emerges from the Great Recession, governments at all levels are grappling with how to ensure the kind of economic growth that will create meaningful jobs and future prosperity. The government of Canada declared 2011 the “Year of the Entrepreneur,” recognizing the critical role of entrepreneurship in securing Canada’s ongoing economic recovery. While celebrating entrepreneurs is important, not all forms of entrepreneurship are equal. High-growth entrepreneurship contributes disproportionately to innovation, job creation and long-term growth potential.

High-growth enterprises — so-called “gazelles” — are young companies that transform markets with radically innovative products, services and processes. Gazelles represent only a fraction of all firms but they outperform all other businesses by generating consistent and extraordinary growth in employment and revenue. These companies start small but quickly grow to become global household names like Facebook and Ikea. Gazelle-type innovation tends to be characterized by firms with high intellectual capital and low physical capital; a steadfast focus on getting products to market quickly and a high responsiveness to market feedback; high-risk, high-reward strategies; and global ambitions.

Gazelles contribute to the lion’s share of new jobs and are more likely than other firms to export their products. By creating new markets and industries, gazelles can also help to diversify an economy and reduce its vulnerability to economic shocks. Successful gazelles pave the way for subsequent entrepreneurs to enter the market by eventually becoming world-class anchor companies whose employees often go on to start complementary or competing future gazelles. Successful entrepreneurs and investors who have been involved in gazelle companies are more likely to create future successful ventures and are important role models and mentors for other entrepreneurs.

Because of its transformative economic impact, high-growth entrepreneurship is gaining the attention of public policy-makers around the world, most notably President Obama, who earlier this year declared high-growth entrepreneurship a central pillar of his economic policy agenda.

While Canada leads the world with our significant public investments in research and development (R&D), our highly educated population and low barriers to starting a business, we have too few innovation-based multinationals — the outcome of successful gazelles. Smaller countries such as Sweden, Finland and Israel punch above their weight, but in Canada, Research in Motion and Cirque du Soleil are exceptions, rather than the rule. The greatest gains stand to be made in Canada’s service sector, which produces a paucity of gazelles relative to those of all other OECD nations.

Several environmental inputs are necessary for the creation of a healthy “gazelle ecosystem” that can support and sustain high-growth entrepreneurship:

- Networks and human capital: Gazelles need strong connections with other players in the gazelle ecosystem, including a base of initial customers who are willing to try, test and give feedback on new products and services. “Clusters” — concentrations of high-growth ventures, in close proximity to universities, think tanks, suppliers and professional associations — establish hubs of activity that become recognized industrial centres of excellence. Links beyond local clusters to leading global clusters such as Silicon Valley that provide world-class connections to technology, customers, financiers and potential employees are crucial. Both “incubators” or “accelerators” — organizations designed to accelerate growth of new ventures through business support services, mentorship and education — and industry associations play a key role in forging connections between investors and entrepreneurs and facilitating the dissemination of best practices. Gazelle survival is also highly dependent on a strong management team and management systems.

- Financing: Strong gazelle ecosystems require investors who are willing to invest at all stages of company growth, but most especially in the early, risky stages. Foreign investors help expand a start-up’s network in foreign markets as well as provide capital. Gazelles also require a banking system that allows financing using receivables or future tax credits as collateral and government programs that reduce exposure to customer risk internationally.

Smaller countries such as Sweden, Finland and Israel punch above their weight, but in Canada, Research in Motion and Cirque du Soleil are exceptions, rather than the rule. The greatest gains stand to be made in Canada’s service sector, which produces a paucity of gazelles relative to those of all other OECD nations.

- Public policy framework: Gazelles require legal systems that respect property rights, including intellectual property promote business; and keep red tape to a minimum. Government can incentivize gazelle formation through tax policy and incentives for R&D spending and commercialization. As a significant procurer of technologies and services, government can also be an important early customer for start-ups.

- Socio-cultural values: A culture that promotes a career in entrepreneurship and risk taking and that tolerates “honourable” failure will create more start-ups and potential gazelles. Political leaders who advocate for entrepreneurship are important public champions. Visible, successful entrepreneurs can also ignite the imagination of future entrepreneurs.

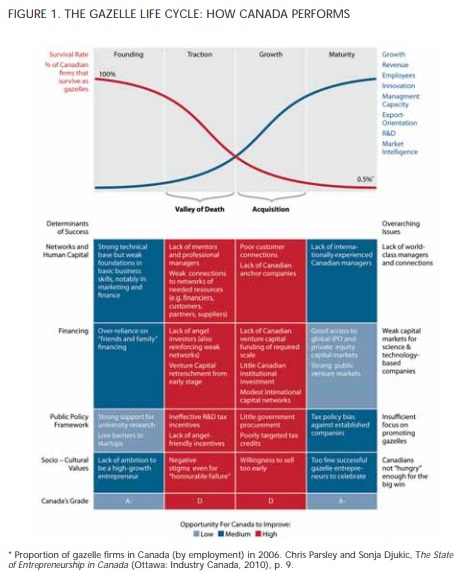

Each of these ecosystem inputs varies in quantity and kind over the life cycle of a firm. Start-ups must pass through four key phases in order to become successful gazelles:

- The Founding Stage spans from the launch of a company to when its first demonstration product is created. During this stage, start-ups are funded by the entrepreneurs and their friends and family.

- In the Traction Stage the company refines its product. Financing during this period is provided primarily by angel investors (high net-worth individuals, typically entrepreneurs who have successfully founded one or more companies themselves) and venture capital funds (independently managed pools of startup capital).

- In the Growth Stage, the business model is validated and the company now requires significant capital from larger financial institutions, professional management teams and access to international markets.

- At the Maturity Stage, growth rates stabilize and the gazelle becomes a large international company.

Canada has very few large public companies that have succeeded through all stages of the gazelle life cycle. Most Canadian start-ups fail to make the transition from the Traction Stage to the Growth Stage, commonly know as the “Valley of Death”: the high-risk, pre-commercialization phase between initial funding of R&D and just before a company is large enough to attract financing from institutional or industry investors. The Valley of Death is often associated with a shortage of financial risk capital, but industry connections, managerial skills and experience of entrepreneurs and their key investors are equally critical to success at this stage. Angel investors play a crucial function by injecting needed cash into fledgling businesses, and by providing management advice and mentorship to entrepreneurs; opening their networks of potential partners, customers and employees; and signalling the business’s potential to the venture capital industry.

Of the Canadian start-ups that make it past the Valley of Death, most fail to move beyond the Growth Stage, either because they are acquired by larger firms or because they may have difficulty obtaining sufficient capital and building the international channels, professional management teams, customer base and partnerships that are required to take growth to the next level. While acquisition in itself can have positive spinoffs, Canada loses the opportunity to retain headquarters with associated R&D functions and corporate expertise that can, in turn, create clusters and attractive jobs.

Mapping the four stages of growth against the four critical dimensions of the entrepreneurial ecosystem provides a comprehensive picture of Canada’s performance (figure 1). This analysis illuminates the most critical barriers to the creation, growth and maturation of gazelles in Canada:

- Missing connections: Canada has many incubators that provide a combination of connectivity, seed funding, mentorship and a workplace for start-ups; however, they are a fragmented system of players of varying size and quality. This can create challenges for smaller clusters trying to make global connections, and for diffusing knowledge and best practices across regions and sectors in Canada. Canadian companies themselves are also less well-networked with key international clusters.

- Shortage of experienced business managers: While Canadian businesses have similar access to scientific and engineering talent relative to our international competitors, our managers have less business training and formal education. Moreover, Canada’s managers generally lack international networks and the experience of learning from past start-up failures and trying again.

- Early-stage funding gap: While venture capital has traditionally been the main source of risk capital for start-ups, the Canadian venture capital industry is in crisis. There has been a sharp drop in fundraising and disbursements, and Canadian funds are retrenching to invest in less risky, later-stage companies. This has left a financing gap for early-stage companies that must increasingly rely on informal investors such as angels, who can be difficult to connect with.

- Lack of sophistication and connectedness of Canadian financiers: In the United States, venture capital funds drive the early adoption of strong managerial systems, but in Canada our venture capital industry is failing to play this role and is underperforming as a result. Canadian venture capital returns are consistently significantly lower than in the United States, likely in part because our venture capitalists tend to lack experience and international connections. Canada also faces a shortage of experienced angel investors who can act as vital screeners of venture capital deal flow.

- University research “push”: Canadians excel at fundamental research but struggle to leverage their results to create successful businesses. Canada invests more as a percentage of its economy in university research than any other OECD country except Sweden. This reflects Canada’s adoption of a “push” strategy based on the implicit assumption that research alone is enough to create innovation-based firms, while ignoring a “pull” strategy that fulfills market demand.

- Ineffective incentives for business R&D: The federal Scientific Research and Experimental Development (SR&ED) refundable tax credit program accounts for approximately 90 percent of Canada’s support for business R&D. However, the program does not require researchers to meet commercialization criteria, and firms are incentivized to define as much of their activities as possible as R&D, even in cases where this work does little to produce innovations. Relative to the US, Canada also spends far less proportionally on direct support for business R&D, such as through the federal Industrial Research Assistance Program (IRAP), which, in addition to financial support for R&D activities, provides important advice, networking and partnerships.

- Insufficient government purchasing incentives: Governments in Canada — usually citing the constraints imposed by trade treaties — have been reluctant to design trade-compliant procurement policies that favour early-stage Canadian companies. All too often, contracts for tender will go to American or European technology goliaths who subcontract to their nonCanadian partners.

- Low ambition: Canadian entrepreneurs often lack the hunger and ambition to compete on a global scale. Canada’s education systems prepare students to be productive employees rather than create their own jobs as successful entrepreneurs. At most Canadian post-secondary institutions, learning about entrepreneurism is confined largely to business schools and not emphasized in innovation-focused disciplines like science and engineering.

In the short term several actions can be taken in Canada to address these specific weaknesses. For instance, on the demand side, more can be done to encourage government procurement, particularly in the knowledge-intensive sectors of health and education. A successful example is the US government’s Small Business Innovation Research program, which requires that major departments allocate 2.5 percent of their internal R&D funding for contracts with qualifying US start-ups. The federal government should also shift the relative funding bias for SR&ED tax credits in favour of increasing direct support like IRAP. A commercialization criterion for SR&ED should also be explored in order to ensure that R&D is being conducted with the intention of generating profits from innovation. To address Canada’s persistent shortage of management talent, we should tap into our expatriate community of entrepreneurs and investors in world-leading clusters like Silicon Valley, as well as attract skilled and experienced managers through a temporary foreign worker program such as in the United Kingdom, where MBA graduates from top business schools around the world are eligible for resident-track visas.

On the demand side, more can be done to encourage government procurement, particularly in the knowledgeintensive sectors of health and education. A successful example is the US government’s Small Business Innovation Research program, which requires that major departments allocate 2.5 percent of their internal R&D funding for contracts with qualifying US start-ups.

Finally, strategic government investment in foreign venture capital funds, along the lines of Israel’s Yozma Program, would increase foreign investor and industry awareness of Canadian start-ups, attract needed risk capital and broaden the networks of Canadian entrepreneurs and investors.

These are piecemeal solutions, however. Over the long term, the most effective actions will be those that mobilize federal and provincial governments, the private sector, educational institutions and others, all of whom share responsibility for laying the foundations of entrepreneurial excellence in Canada. What Canada needs most urgently is a national strategy to marshal the collaborative efforts of these stakeholders in creating much more favourable conditions for the emergence of Canadian gazelles.

The cornerstone for a national strategy should be a central enabling organization with a mandate to fuel high-growth entrepreneurship in Canada. In the US, President Obama announced Startup America, an initiative that is rallying private sector partners and resources, in concert with federal agencies, to connect the country’s most innovative entrepreneurs with leaders from top corporations, universities and non-profit organizations, to spur the creation of more high-growth firms across all regions. Startup America is investing in research, training and collaboration to scale up successful community-based entrepreneurship accelerator programs, develop new entrepreneurship education and mentorship programs and identify and remove barriers to the commercialization of research. Canada must adopt a similar approach. The “Startup Canada Partnership” should be created by federal statute and endowed by both government and industry but should remain at arm’s length from both and should be given a broad mandate to conduct research and identify best practices to understand how we can improve performance, better equip our entrepreneurs and investors through rigorous training and become the nexus for university research centres, entrepreneurs, investors and mentors.

Second, the systemic shortage of “smart” early-stage risk capital in Canada must be addressed. The federal government should work with the provinces to establish a national angel tax credit, funded equally by both levels of government, designed to allow each province to target specific industries that are deemed a priority for the creation of clusters and to enable angel investors from any province to be eligible for tax credits when investing in any other jurisdiction.

Third, Canada must do more to prepare its next generation of innovation leaders and foster the ambition and desire to compete and succeed on a global scale. Post-secondary institutions should deliver cross-disciplinary courses and programs where engineering and science students learn and work with business students to build their understanding of how to connect a product to customers and markets. Similarly, universities should encourage, or at least permit, faculty to take a leave of absence to join start-ups, helping them gain practical knowledge that can be shared with students.

Finally, evidence-based policy and decision-making must be strengthened. Policy-makers and industry associations currently have an incomplete picture of enterprise activity in Canada and lack a solid empirical understanding of the factors that drive successful gazelle companies. Federal and provincial governments, as well as industry associations, must work together to develop data collection systems that will yield more and better information to assist policy-makers and industry associations in designing effective policies and programs specific to gazelle companies.

Canada needs more enterprises that are sufficiently innovative and ambitious to compete on a global scale and bring sustainable job creation and economic growth to future generations. Without a strategy to accelerate our high-growth start-ups and keep them anchored in Canada, we will continue to trail international competition and, more critically, will risk both our economic recovery and long-term prosperity.

This article is an abridged version of their task force report Fuelling Canada’s

Economic Success: A National Strategy for High-Growth Entrepreneurship, available at www.actioncanada.ca.

Photo: Shutterstock