The United Kingdom’s election result will bring about profound and lasting change. After months of parliamentary gridlock during which the prime minister, like his predecessor, was unable to marshal the numbers in the House of Commons to pass his Brexit deal, he called an early election, hoping for a more favourable parliamentary composition.

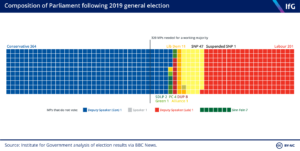

The gamble has paid off. After winning with 365 of 650 seats in the House of Commons, Johnson has led the Conservative Party to its best election result since 1987. Labour, meanwhile, registered its worst result since 1935. With such a comfortable majority, Johnson now has a degree of freedom to pursue his preferred form of Brexit – and focus on other priorities – in a way that was unthinkable before the election.

But this is only the beginning of the Brexit process

Johnson’s first task is to get the Withdrawal Agreement passed to settle the terms of the UK’s divorce from the EU. The legislation must be approved by January 29, ahead of the January 31 deadline for the UK’s formal departure – at which point it enters an 11-month transition period lasting until December 31, 2020. During this period, the UK would continue to apply EU law, while being outside of the EU’s political institutions.

But the agreement only covers the terms of the UK’s departure – the financial settlement, citizens’ rights and the question of the Irish border. It does not determine the UK’s future relationship with the EU. This will be the subject of a second, and far more complicated, phase of talks covering a wide range of complex topics including trade, security co-operation, financial services and fishing rights. The outcome will govern the relationship between the UK and the EU for decades.

Over the coming months, the prime minister will face difficult negotiations in securing this relationship. A deal must be agreed – and ratified – when the transition period ends on December 31, 2020, and Johnson has vowed to outlaw any extension, legally binding himself to the deadline. This means the risk of a “no-deal Brexit” is again very real. This would mean border checks for goods and potential interruption of supply chains, loss of access to the EU single market for service industries and immediate departure from EU institutions like the European Court of Justice (ECJ) and Europol, the law enforcement body.

Even if the future relationship terms are settled, the process of adapting to new political and economic arrangements will likely take years.

Brexit places pressure on the future of the UK

While Johnson’s majority may seemingly offer some certainty regarding immediate next steps with the EU, December’s election results also place a huge strain on another political union, that of the UK.

Scotland voted overwhelmingly for the Scottish National Party (SNP), which has called for a referendum on Scotland’s independence from the UK – but such a referendum cannot happen without the approval of Johnson’s government. The SNP’s strong showing (claiming 48 of Scotland’s 59 seats), against a backdrop of Scottish resistance to Brexit sets up a showdown between the SNP’s claimed mandate for a further independence referendum and Johnson’s refusal to give his government’s approval for one.

Elsewhere in the UK, the results also returned, for the first time, a majority of nationalist MPs in Northern Ireland – those from parties that support leaving the UK in favour of reunification with the Republic of Ireland. Johnson’s Brexit deal, which treats Northern Ireland differently from the rest of the UK, may well give momentum to those seeking Irish reunification, and result in another headache for the prime minister.

The government must bridge the gap between promises and reality

Johnson will also have to deal with the universal challenge of government: reconciling voters’ expectations of services with their reluctance to pay for them. He will also need to fill in the details on some key policies.

The government has pledged to ramp up spending on schools and the NHS, and to hire 50,000 more nurses to deliver on its promise of “world-class” public services. The investment is welcome. Funding for many public services was squeezed by the austerity policies brought in by the coalition government in 2010 following the 2008 financial crisis. But Institute for Government calculations show the sums promised are only enough to maintain standards, not improve them. And there is little room in the medium term for the government to raise this spending without abandoning either its own fiscal rules or its pledge not to increase personal income taxes.

Plans for elder care are scant. While the government has promised to work towards a “cross-party consensus to bring forward an answer that solves the problem”, past attempts to sort out how much individuals and the state should pay have fallen victim to partisan point-scoring.

Lack of detail is also glaring on plans for the post-Brexit immigration system. The phrase “Australian-style points system” has become ubiquitous – something of an exemplar for those wanting a firmer approach (despite Australia’s relatively high levels of migration), with a hint to business of an openness to skilled migrants. But the government has not spelled out what this slogan might mean in the UK context.

Early hints suggest some confusion. The Conservatives’ statement that “most immigrants will need a job offer” is at odds with the Australian model in which, like Canada’s, visas are awarded based on attributes like education, language skills and work experience, rather than a confirmed job offer. Johnson will need to make decisions soon, having promised to introduce legislation within the first 100 days of the new Parliament.

No rest for the civil service in sight

The civil servants who will deliver Johnson’s agenda have been under considerable strain. Rates of work-related stress, depression and anxiety in the civil service are at their highest levels in decades, and have been attributed to the intensity and uncertainty of Brexit, staff turnover and pay restraint. Some departments have resorted to shift work to cope with the Brexit workload, others have offered counselling. Turnover is a long-standing problem that has been exacerbated by Brexit: in 2016-17, more than four in 10 senior officials had been in their positions for less than a year.

Any post-election machinery of government changes will lead to more disruption. The Institute for Government has found the hit to morale and productivity can cost up to £34m a year for the creation of a medium-sized policy department, with a two-year timeframe for departments to be properly up and running. The government is yet to confirm any changes, but a merger of the Department for International Development and the Foreign Office is rumoured – not unlike the Harper government’s decision to merge the Canadian International Development Agency with the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade in 2013.

The election result has strengthened Johnson’s hand, within his own party and in Parliament. It has done nothing, however, to answer the question of how he intends to govern – or how he will approach some of the most momentous decisions a prime minister has had to make in decades.

This piece was adapted from an article originally published by The Mandarin.

Photo: Calgary Co-op, a cannabis retailer, in the downtown core.

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.