Justin Trudeau cannot in this new session of Parliament rely on having the outcomes his father did in 1972. True, both he and Pierre Trudeau experienced the embarrassment of moving from a resounding popular victory in their first election cycle to near defeat in the second, after both had been considered the principle reason for resounding victory four years earlier.

But further comparisons between the 2019 and 1972 elections, tempting as they may be, risk being superficial and misleading for anyone attempting to predict the success of the new Liberal government.

To begin with, the 1972 campaign consisted of the Liberal, Progressive Conservative, New Democratic and Social Credit parties. There was no People’s Party, Bloc Québécois or Green Party.

After the 1972 election, Pierre Trudeau needed a reliable ally to help him govern, and the NDP by itself could ensure a majority vote in the House. Yes, in both the 1972 and 2019 elections, the popular vote in most provinces showed a decline in the Liberal vote and an increase in the Progressive Conservative/Conservative vote. But there was a important difference in the degree of the decline. Pierre Trudeau’s popular vote dropped 9.7 percent between 1968 and 1972, and Justin Trudeau’s dropped 6.5 percent between 2015 and 2019.

The principal reason for the drop in 2019 is that both Liberals and Conservatives attracted a smaller percentage of the popular vote in Ontario. The Conservatives made no breakthroughs. but made modest gains in all the other provinces except Quebec.

The Progressive Conservatives/Conservatives picked up seats in British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba in both elections, but in 1972 owed their success to gaining the majority of seats in Ontario – more than doubling their representation. In contrast, in 2019, the Conservative Party made minor gains in seats and failed to gain in the popular vote in Ontario. In the ’72 election, the PCs gained seats on the Prairies, but they had already gained a majority of Prairie seats in the 1968 election. Significantly, in 1972, the NDP also made substantial gains in BC and retained seats in Saskatchewan and Manitoba, which gave some credibility to the possibility that with their support the Liberals would could survive as a government.

In 1972, there were no new high-profile issues. The Prairies believed that the Liberals were passive about western agriculture, and the west was cooler toward bilingual and biculturalism than the rest of Canada. Crucially, while there were east-west strains, national unity was not front and centre. In Quebec, where Trudeau held the majority of seats, there was yet to be a real political split between separatism and federalism. Energy policy would not become an issue until 1974. This difference stands in sharp contrast to the profile of issues around energy, climate change and national unity in the 2019 election.

In 1972 the Pierre Trudeau government was given a rebuke and wake-up call after being seen as being technocratic, arrogant and drifting out of touch. The Liberals’ campaign slogan “The Land is Strong” was a bust, seeming to underline the “out of touch” argument. But while seen by many disenchanted voters as being too detached, he was charismatic and regarded as a strong presence. In 2019, Justin Trudeau faced the electorate in circumstances that were very different those his father faced. Now he, unlike his father, must attempt to redefine himself for Canadians while readdressing the issues of energy and climate change. This will be difficult; the Liberals may well have a challenge addressing the diametrically opposed pressures from the Greens and the NDP, on the one hand, and the Conservatives and their provincial allies, on the other.

In this recent election the dominant policy discussions were blurred by damage to Justin Trudeau’s image as a result of handling of the SNC-Lavalin affair, serious questions about the treatment of Vice-Admiral Mark Norman, the PM’s behaviour toward two of his capable female ministers, as well as his personal interest in costumes and blackface. These issues have raised real questions about what he really believes in. Could it all have been a well-conceived political act?

Pierre Trudeau, like his son, was not well regarded on the Prairies, but he nevertheless had seats in all provinces but Alberta. As well, he corrected his image problem by becoming more engaged with Canadians between the 1972 and 1974 elections, and in skillfully putting the PCs on the defensive on wage and price controls and the east-west oil-pricing policy. Indeed, the West’s concerns over the Liberal’s energy policy only began in 1974, and they were exacerbated by the National Energy Policy in 1980. It can fairly be said that the father’s energy policies laid the ground for the western attitudes that met Justin Trudeau when he became leader of the Liberal Party.

In 1972, the Progressive Conservative leader Robert Stanfield did not have Pierre Trudeau’s charisma, and he was dogged by a party rump that was led by Alberta MP Jack Horner and encouraged by John Diefenbaker. Nonetheless, he was well regarded by the electorate. While there were damaging divisions in the party, generally the public saw Stanfield as intelligent, honourable, and part of the mainstream of Canadian politics, so there was little hesitation in trusting him with their vote. In contrast, Conservative leader Andrew Scheer had trouble capitalizing on the dissatisfaction with Justin Trudeau, and Canadians were not as ready to trust him with their anti-government votes.

The voters chastised Pierre Trudeau in 1972. But the electorate wanted to punish Justin Trudeau in 2019, and if it had not been for the considerable reluctance of Ontario voters to show confidence in the alternative provided by Scheer, Trudeau might well have been the Leader of the Official Opposition.

To ensure re-election, Pierre Trudeau had to re-engage as a retail politician. Justin Trudeau has also been a retail politician. But, unlike his father, he cannot rely on one party for support if he is to address a seriously divided country and rebuild public confidence in his personal bona fides. He will have to play a very clever game of chess with the different expectations of the four parties in opposition if he is to bridge those gaps.

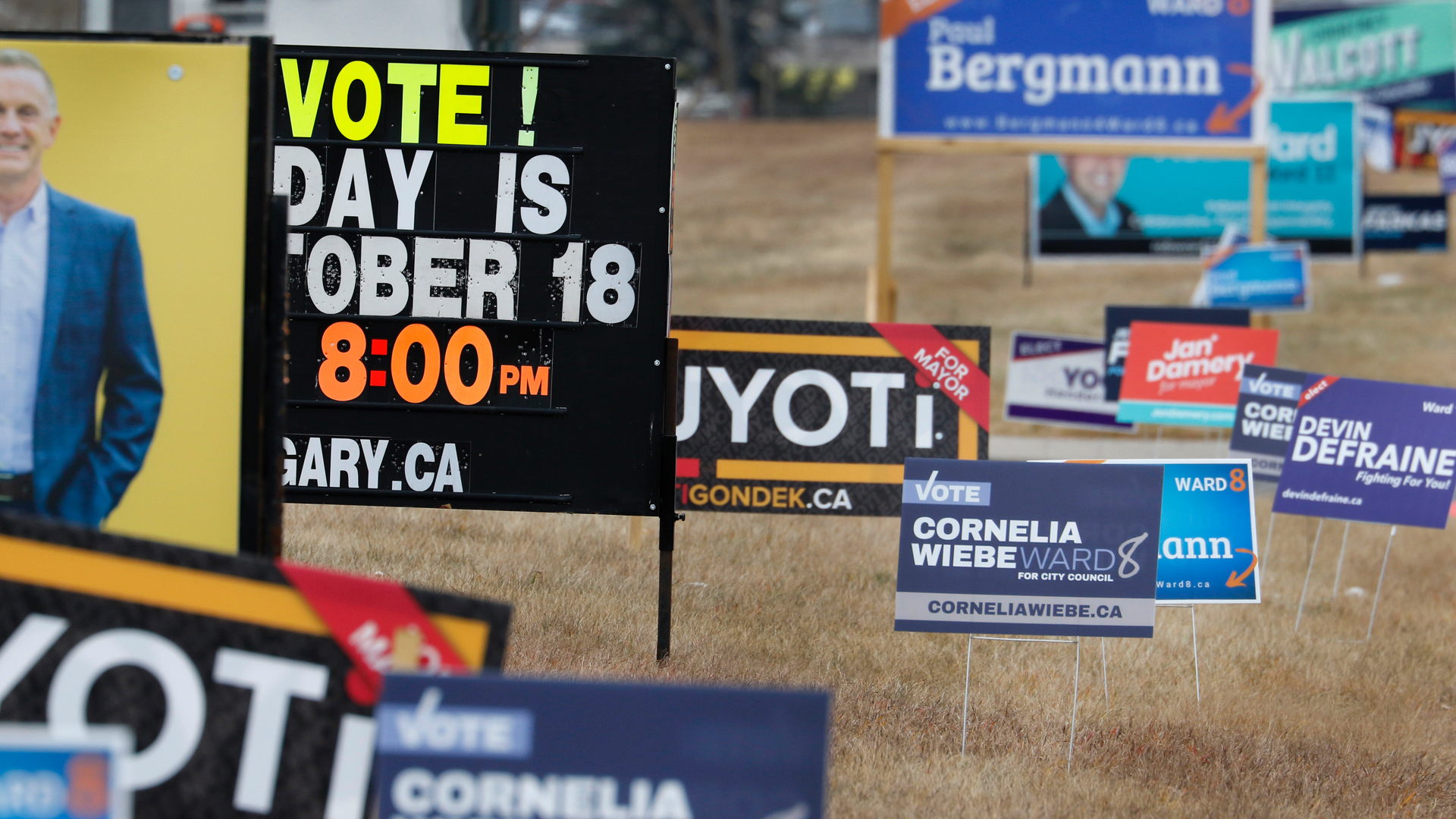

Photo: Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and Liberal cabinet minister Allan MacEachen on election day Oct. 30, 1972. CP PHOTO/ Peter Bregg

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.