The term “development” often leads people to think of good causes and aid programs, but not necessarily matters of strategic and economic importance to Canada. One of the new realities that motivates the IRPP’s trade volume is that developing and emerging economies are fast becoming major trade and investment partners, and so fostering linkages with and among them is an essential part of promoting global growth and reducing poverty.

In her chapter for the volume, Margaret Biggs (professor at Queen’s University and a former president of the Canadian International Development Agency), argues for fresh thinking on “trade and development.” She analyzes the implications of several dramatic global economic, political and social trends for Canadian trade and development policies, and identifies strategic opportunities for Canadian leadership. Biggs argues that “inclusive trade” — trade that is inclusive of developing and emerging countries and which advances shared prosperity within countries — is now central to the future of the international trading system and to any conception of a progressive trade agenda for Canada. She concludes that Canada is well positioned to find creative ways to integrate trade and development for the benefit of developing and advanced economies.

New global realities for trade and development

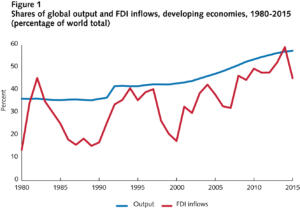

Dramatic global shifts are turning the postwar trading system on its head, with important implications for how trade and development are understood and pursued across the globe. Economic dynamism and heft have clearly shifted towards developing economies over the past few decades. As figure 1 shows, in recent years, these countries have come to collectively account for the majority of global GDP and inward foreign direct investment (FDI).

These shifts have created new commercial opportunities, and developing economies have become much-needed engines of growth at a time when the global economy desperately needs a boost. Unfortunately, Canadian firms have been slow to engage with them, relative to the opportunities and to peer countries. For example, of the G7 countries, Canada has the lowest exports per capita to, and the lowest share of total exports destined for, developing countries (figure 2).

Another important development is that fact that production, trade and investment patterns are increasingly being shaped by global value chains. This puts a premium on moving goods and services across international borders (i.e., trade facilitation), and on “behind the border” domestic policies, such as investment rules, regulatory regimes and labour and environmental standards. At the same time, trade policy attention in many developed countries has shifted away from the multilateral forum of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and toward preferential trade arrangements (largely in order to address these new policy issues with like-minded partners). Ironically, this move away from the WTO coincides with renewed attention to trade and investment on the part of developing countries and a new consensus on the importance of leveraging trade to reduce poverty and stimulate inclusive growth.

Finally, of course, all these shifts are now being influenced by protectionist pressures and antiglobalization sentiments that have arisen in many advanced economies, as a result of elevated inequality and growing economic insecurity.

Implications for trade and development

Open markets and trade liberalization are essential for developing countries to reduce poverty and advance sustainable growth. As such, developing countries have a keen interest in reinvigorating a rules-based, nondiscriminatory multilateral trading regime — and much to lose from its fragmentation and erosion. At present, there are major risks for these economies, which are largely excluded from recent agreements and are ill-equipped to handle the more complex global trading system that’s being carved out as new trade rules are developed.

Developing countries also need to focus on reducing barriers to south-south trade and overcoming a reluctance to open their own markets, which is so essential to economic efficiency and GVC participation. And while the issue of having different measures and concessions for developing countries (so called “special and differential treatment”) still matters — especially for the least-developed countries — it needs to be reframed, not in terms of whether developing countries should adhere to multilateral norms, but rather in terms of how quickly they can and how their capacity gaps can be addressed.

A way forward: Inclusive trade and inclusive development

In previous decades, it was mainly developing countries that raised questions about the effect of trade on economic development, the distribution of its benefits, and the ability of their governments to protect domestic policy priorities. Now, however, the question of how trade can advance shared prosperity and improve the welfare of all citizens is at the core of contemporary political and economic dynamics in all countries. We refer to it here as inclusive trade.

The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide a new way of looking at trade issues—thinking about inclusive trade and seeing trade as an issue that can’t be viewed in isolation from other economic, social and environmental factors that are needed for inclusive growth and sustainable development. The universality of the SDGs can also help break down the us-versus-them mentality that often gets in the way of mutual understanding and progress at the WTO. For example, the impact of trade on income inequality, gender and the environment is of global importance, as is progress on job creation, clean energy, and better integrating small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) into global commerce.

Opportunities for Canadian leadership

To achieve the vital objectives of open and inclusive trade and to facilitate the integration of developing economies into the global trading system, Canada should focus on five priorities for action.

First, the relevance and inclusiveness of the multilateral trading system should be strengthened. Canada is well placed to lead in this, given its G7 and G20 connections and its extensive outreach across the developing world, its experience with preferential trade agreements, and its credibility as a country committed to openness. Canada has the convening power to bridge divides. It should spearhead the search for practical ideas, experimentation and institutional innovation toward making the WTO more relevant on contemporary trade, investment and regulatory issues, and it should knit the myriad of preferential trade agreements into a more coherent and inclusive multilateral whole. We can also provide leadership by examining our overall trade policy from the standpoints of the opportunities and risks it poses for strengthening the multilateral trading system and of supporting developing countries. We should use the SDG and G20 reporting frameworks to push ourselves and others to track progress on agreed on goals and commitments.

Second, after Canada’s recent ratification of the WTO’s landmark Trade Facilitation Agreement (2013), we now need to lend our development and trade policy heft to helping developing countries address their capacity gaps and meet their TFA commitments. The TFA aims to expedite the movement of goods across international borders by creating norms for customs and logistics at the border. The dividends accruing from it could be sizable. The WTO estimates that full implementation of the TFA could generate 20 million new jobs, the vast majority of them in developing countries. As well, it could boost global merchandise exports by up to $1 trillion annually, including $730 million in developing countries. Canada could also go further and initiate a move to broaden the TFA to cover the facilitation of responsible investment. After all, in a world of global value chains, trade facilitation only addresses one side of the trade and investment equation.

Third, a concerted “inclusive trade, inclusive development” strategy is required in Canada’s global development and international assistance efforts, consistent with developing countries’ priorities and needs. Canada needs to prioritize inclusive trade as a key driver for reducing poverty and stimulating sustainable and inclusive growth. Canada should focus on the job-creation and poverty-reduction effects of women’s economic empowerment and SMEs’ competitiveness (see Arancha González’s prereleased chapter for the IRPPs trade book); supporting low income and least developed countries’ efforts to build competitiveness and trade; and bringing an integrated trade and investment global value chain lens to bear on its development programs.

Fourth, Canada needs a sea change in the way it approaches two-way trade and investment with developing economies. Business-as-usual approaches won’t get Canadian investors and firms to the high-growth frontiers of global economic activity. To go global, Canada must think bigger. We need to brand ourselves as a trade and investment partner of choice; launch the next generation of innovative trade-promotion initiatives; and fast-track a Canadian development finance institution (DFI) of global scale and ambition. DFIs play a crucial role in facilitating the deployment of commercial capital for public policy purposes in developing countries. The need for development finance has never been greater, given the unprecedented levels of investment needed in developing countries in areas such as climate-smart transport, connectivity, water and sewage, clean energy and energy efficiency. The goal of a best-in-class DFI should be to attract private capital without competing with private sources of finance, and to demonstrate clear development impacts. A Canadian DFI would make it easier for Canadian firms to jump to the frontiers of global economic activity and to contribute to addressing global sustainable development challenges.

Finally, at its best, Canada can serve as a model for how to build an open and inclusive economy and avoid serious social fault lines like those that have emerged in other countries. It is an open question, however, as to whether Canada’s current mix of social and labour market measures is fit for purpose in light of elevated income inequality, technological change and a rapidly changing labour market. Two urgent priorities are to rethink employment insurance and modernize Canada’ portfolio of skills development policies and programs.

Now is the time for Canada to provide policy and political leadership on inclusive trade at the global level. The challenges ahead require deep and sustained commitment to constructive engagement and practical problem-solving. With the US and Europe preoccupied with domestic issues and antitrade sentiments, rarely has there been such a structural global leadership gap among advanced economies on global trade. Canada’s interests and values on trade and development are currently aligned, and with the 2017 WTO Ministerial and Canada’s 2018 G7 presidency on the horizon, we have a major policy window to act. But the work must start now if we are to build a new global coalition for open, inclusive trade and development.

Photo: Daniel William / Shutterstock.com

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.