As Chinese outward foreign direct investment (FDI) becomes a major force in the international economy, two questions are of central interest to policy-makers in Canada and elsewhere. First, what is the impact of Chinese FDI on the structure of natural resource industries around the globe? Second, when does the foreign acquisition of an existing firm constitute a genuine national security threat to the home country of the acquired firm? Treatment of these two issues requires separate and distinctive modes of analysis, but the conclusions intersect in important ways.

Dealing first with the impact of Chinese FDI on natural resource industries, one might ask whether the growing number of Chinese investments in these sectors have the effect of “locking up” the global resource base. Conversely, might Chinese investments, loans and long-term contracts constitute a positive influence for non-Chinese buyers, helping to multiply suppliers and expand competitive entrée to the world resource base?

On the demand side, China’s appetite for vast amounts of energy and minerals clearly puts tremendous strain on the international natural resource sector. On the supply side, Chinese efforts to procure raw materials might indeed exacerbate the problems of strong demand or they might actually help solve the problems of strong demand. The outcome depends on whether those arrangements enhance Chinese ownership and control within a concentrated global supplier system or whether they expand, diversify and make more competitive the global supplier system.

I and my colleagues at the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) have investigated this question as an empirical inquiry, with the opening premise that either outcome is possible. The Chinese deployment of capital to procure natural resources takes four forms:

- Chinese investors take an equity stake in a large established producer so as to secure a share of production on terms comparable to other co-owners.

- Chinese investors take an equity stake in an up-and-coming producer so as to secure a share of production on terms comparable to other co-owners.

- Chinese buyers and/or the Chinese government provide financing to a large established producer in return for a purchase agreement to service the loan.

- Chinese buyers and/or the Chinese government provide financing to an up-and-coming producer in return for a purchase agreement to service the loan.

These four structures provide the basis for giving operational definition to the concept of “tying up” supplies.

If the procurement arrangement simply solidifies legal claim to a portion of the output of an established large producer (options 1 and 3 above, which I will refer to as category I), “tying up” or gaining “preferential access” to supplies has zero-sum implications for other consumers. However, if the procurement arrangement expands and diversifies sources of output more rapidly than growth in world demand (options 2 and 4, which I will refer to as category 2), the zero-sum implication vanishes as other consumers gain easier access to a larger and more competitive global resource base.

The impact of Chinese procurement arrangements on the structure of natural resource industries around the world is only one dimension of the geopolitical challenges

surrounding these endeavours.

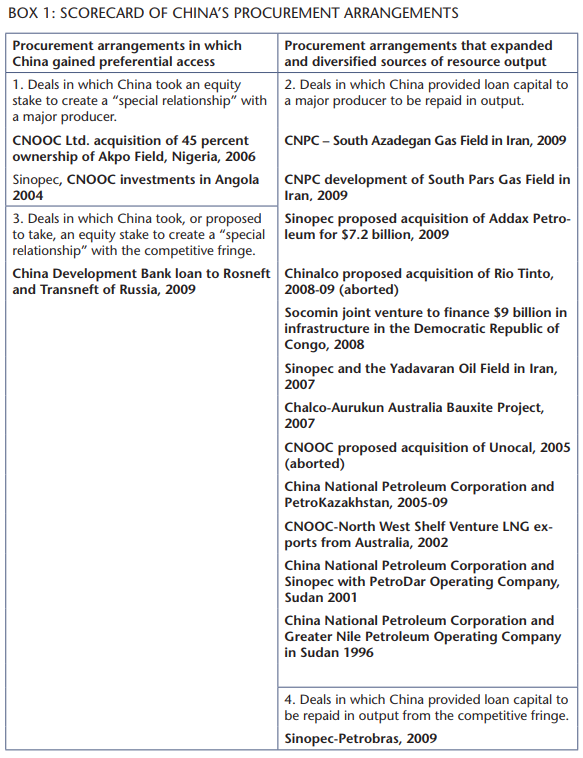

Box 1, which draws on PIIE research carried out in 2010, classifies 16 large Chinese natural resource procurement arrangements around the world under the four categories above. The scorecard of China’s procurement arrangements shows a few instances in which Chinese natural resource companies took an equity stake to create a “special relationship” with a major producer. But the predominant pattern (in 13 of the 16 projects) was an arrangement in which a Chinese company purchased an equity stake and/or entered into a long-term procurement contract with what economists refer to as the “competitive fringe” — a smaller player or new entrant.

As a follow-on project, in 2011 we undertook a comprehensive examination of the universe of 35 Chinese natural resource investments and procurement arrangements in Latin America. Of these 35, 23 serve to help diversify and make more competitive the portion of the world natural resource base located in Latin America, and 12 do not. Thus the predominant impact of Chinese procurement arrangements does not support popular concerns about Chinese “lock-up” of world resources.

Of course, the impact of Chinese procurement arrangements on the structure of natural resource industries around the world is only one dimension of the geopolitical challenges surrounding these endeavours (box 1). It must also be noted that some Chinese natural resource investments flow to problematic states and regions, including Iran, Sudan and Myanmar. Such investments can expose individual host countries in the developing world to so-called resource curse practices of illicit payments, graft and corruption, as well as poor treatment of workers and lax environmental standards. In a recent World Investment Report devoted to transnational corporations, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) notes that non-OECD investors — most prominently Chinese investors operating under a doctrine officially labeled “non-interference in domestic affairs” — often undermine hard-won governance standards observed by other multinational corporations. These governance standards include home country legislation that conforms to the OECD Convention on Combating Bribery, such as the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

Some Chinese companies have also ignored or bypassed best-practice environmental standards insisted upon elsewhere.

In addition, it must be acknowledged that not all Chinese strategic manoeuvres toward natural resource procurement reflect the predominant trend of making the supplier base more competitive. Indeed, Chinese policies to exercise control over “rare earth” mining run precisely in the opposite direction. Rare earth elements (REE) are crucial for a wide array of civilian and military products. In 2009-10 China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology set an export quota of 35,000 tons of REEs per year, with a potential ban on exports of at least five types, and other steps to control mining. Chinese investors have simultaneously sought equity stakes in new REE producers, particularly in Australia. Deng Xiaoping is often quoted as pointing out that while the Middle East has oil, China has REEs.

This propensity on the part of Chinese authorities to play a role as a quasi-monopolist in REEs should be kept in mind when assessing Chinese proposals to acquire other sources of scarce natural resources, such as Canadian REEs or — perhaps — potash.

Foreign direct investment that occurs through the acquisition of an existing company has long been the subject of particular sensitivity around the world, with frequent allegations that the outcome might negatively affect the national security of the home country. Within OECD states, an estimated 80 percent or more of all FDI takes place via acquisition of existing firms, rather than as greenfield investments.

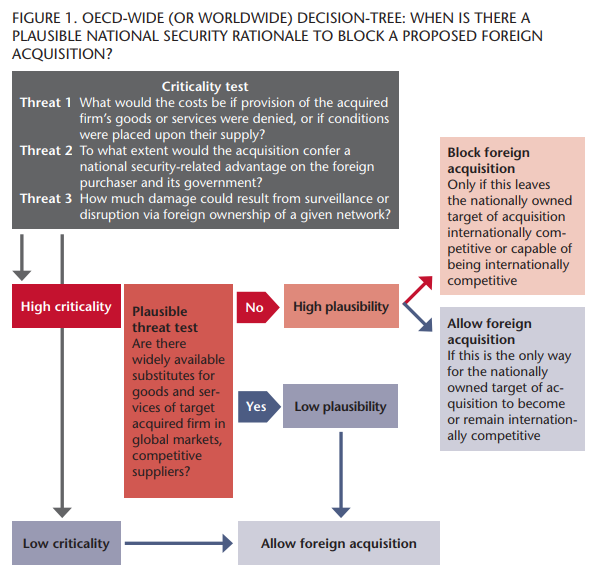

In the United States, policy-makers have grappled with the notion of what constitutes a national security threat for more than 20 years; the US experience offers a useful framework for other nations as well. The cases that have dominated US analytical focus since the enactment of the 1988 Exon-Florio Amendment — which authorized the president to investigate foreign investments in US companies from a national security perspective — suggest that potential threats to national security resulting from such investments fall into three distinct categories (the “three threats”; see figure 1):

- Acquisitions that would make the home country dependent upon a foreign-controlled supplier that might delay, deny, or place conditions on the provision of goods or services that are crucial to the functioning of the home economy (including the functioning of the defence industrial base).

- Acquisitions that would allow the transfer to a foreign-controlled entity of technology or other expertise that might be deployed by the entity or its government in a manner that is harmful to the home country’s national interests.

- Acquisitions that would enable the insertion of some potential capability for infiltration, surveillance or sabotage — via a human or nonhuman agent — into the provision of goods or services that are crucial to the functioning of the home economy (including, but not exclusively, the functioning of the defence industrial base).

The enactment of the Exon-Florio provision in 1988 reflected broad concern about the possible decline of US high-tech industries, aggravated by aggressive competition and increased investment flows from Japan — not unlike some contemporary apprehensions about China. A brief review of the US historical experience may be instructive for Canadian authorities seeking to address national security considerations under the Investment Canada Act.

Foreign direct investment that occurs through the

acquisition of an existing company has long been the subject of particular sensitivity around the world, with frequent allegations that the outcome might negatively affect the national security of the home country.

The case that provided much of the impetus behind the passage of the Exon-Florio provision was the proposed sale of Fairchild Semiconductor by Schlumberger of France to Fujitsu in 1987. Opponents of the sale voiced concern that it would give Japan control over a major supplier of microchips to the US military. In the end, Fujitsu withdrew its bid before US authorities could conduct extensive analysis to determine whether there were sufficient grounds to fear foreign “control” and excessive “dependence.”

Criticism of the proposed acquisition rested on the premise that the target firm was in an industry “crucial” to the US economy and defence. However, in the Fairchild Semiconductor case there was no careful analysis of the conditions under which supply could be manipulated, or whether such manipulation would have any practical impact.

This changed in 1989 with the battle over Nikon’s proposal to acquire PerkinElmer’s stepper division. Steppers are advanced lithography systems used to imprint circuit patterns on silicon wafers in the semiconductor industry. At the time of the proposed acquisition, Nikon controlled roughly half of the global market for optical lithography and Canon, another Japanese firm, controlled another fifth. If the acquisition had been allowed to proceed, US producers would have been highly constrained with regard to their purchases of machinery to etch microcircuits on semiconductors. The sale would effectively place quasi-monopoly power in the hands of the new owner, and — by extension — the Japanese government. The novel insight from the PerkinElmer case was that the term “crucial” — namely, the cost of doing without — had to be joined with a parallel consideration: for there to be a credible likelihood that a good or service can be withheld at great cost to the economy, or that the suppliers (or their home governments) can place conditions upon the provision of the good or service, the industry must be tightly concentrated, the number of close substitutes limited and the switching costs high.

Of particular note is that for there to be a credible risk to national security in a highly concentrated industry, it is not necessary that the home government of the acquirer be an “enemy” of the nation in which the acquisition would take place, nor that the home government have an ownership stake in the acquirer. Even though the US-Japan foreign policy relationship was broadly cooperative, it was not inconceivable that the Japanese government might instruct US subsidiaries of Japanese companies to behave in ways inimical to US national interests. In a case not involving any acquisition whatsoever, Japan’s Ministry of International Trade and Industry, under pressure from socialist members of the Diet, did force Dexel, the US subsidiary of Kyocera, to withhold advanced ceramic technology from the US Tomahawk cruise missile program.

The relevance of this growing insight about concentration, substitutes and switching costs becomes more apparent if one jumps ahead in time to consider the case of a Russian oligarch’s 2006 purchase of Oregon Steel. The acquirer was the Russian company Evraz, which is partly owned by Roman Abramovich, a Russian billionaire with close ties to the Kremlin. In the public debate over this deal, the word “crucial” was sometimes replaced with “critical,” with the same implication of a high cost if supply were manipulated.

Did the Evraz-Oregon Steel takeover represent a national security threat to the United States? To determine if a foreign acquisition such as this poses a threat, analysts have to evaluate both whether the good or service provided by the foreign-acquired firm is crucial to the functioning of a country’s economy (including but not limited to its military services), and whether there is a credible likelihood that the acquirer or its home government could withhold or place conditions on supplies of the good or service.

The purchase of Oregon Steel by Evraz clearly meets the first test. Steel is a major component of military equipment ranging from warships, tanks and artillery to components and subassemblies of myriad defence systems. Uninterrupted access to steel is also crucial for the everyday functioning of the US civilian economy.

But the second evaluation dispels those concerns: in the international steel industry, the top four exporting countries account for no more than 40 percent of the global steel trade. Alternative sources of supply are widely dispersed, with nine countries apart from Russia that export more than 10 million metric tons a year, and 20 more suppliers that export more than 5 million metric tons a year. It is difficult to imagine a scenario in which the Russian government or a Russian oligarch could manipulate output from Oregon Steel in a way that was more than a minor inconvenience to buyers in the United States. The globalization of steel production allows US customers to take advantage of the most efficient and lowest-cost sources of supply without concern that the United States is becoming “too dependent” on foreigners.

Almost by definition, a proposed foreign acquisition offers the buyer some production or managerial expertise that it did not formerly possess. This in turn provides the home government of the foreign parent with an opportunity to control or influence the ways in which that expertise is deployed. Often this additional production or managerial expertise can be seen as strengthening, if only marginally, that government’s national defence capabilities.

So this second test interacts with the first: How broadly available is the additional production or managerial expertise involved, and how big a difference would the acquisition make for the new home government? The prototypical illustration of potentially worrisome technology transfer can be found in the landmark case of the proposed acquisition of LTV Corporation’s missile business by Thomson-CSF of France in 1992. Some of LTV’s missile division capabilities were sufficiently close to those of multiple alternative suppliers that Thomson-CSF could obtain them elsewhere with relative ease. However, three product lines — the MLRS multiple rocket launcher, the ATACM long-range rocket launcher and the LOSAT anti-tank missile — had few or no comparable substitutes. Another, the ERINT anti-tactical missile interceptor, included highly classified technology that was at least a generation ahead of rival systems.

Thomson-CSF was 58 percent owned by the French government and had a long history of following French government directives. The potential for sovereign conflict over the disposition and timing of Thomson-CSF sales, should the LTV missile division become part of the group, was substantial. Prior Thomson-CSF sales to Libya and Iraq had already provoked considerable controversy; for example, a Thomsonbuilt Crotale missile had shot down the sole US plane lost in the 1986 US bombing raid on Tripoli, and Thomson radar had offered Iraq advance warning in the first Gulf War.

The US Department of Defense initially informed Congress that it would insist on a special security agreement, or blind trust, to perform the security work on LTV programs, an arrangement at first opposed by Thomson-CSF but ultimately accepted. Later, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), an interagency government committee that reviews the national security implications of foreign investments, rejected the proposed acquisition when Thomson and the Pentagon failed to agree on how to protect sensitive US technology.

Thus the methodology for determining whether a foreign acquisition might result in the “leakage” of technology or other sensitive knowledge follows the same path outlined above. The key lies in calculating the concentration or dispersion of the particular capabilities possessed by the acquired entity. When the entity possesses unique or tightly held capabilities that might be deployed in ways that could damage the national security interests of the home country, the risk is genuine.

The Dubai Ports World (DPW) case brought to the fore an additional concern — namely, that a foreign owner might be less than vigilant in preventing hostile forces from infiltrating the operations of an acquired company or might even be complicit in facilitating surveillance or sabotage. In 2005, DPW sought to acquire the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company (P&O), a British firm. P&O’s main assets were terminal facilities owned or leased in various ports around the world, including in six US cities: Baltimore, Houston, Miami, New Orleans, Newark and Philadelphia. This time, CFIUS initially approved the acquisition.

The issue in the DPW case was not whether foreign ownership of a given service provider might lead to a denial of services at the behest of the new owner or its home government. Nor was there a concern that sensitive technology or other management capabilities might be transferred to the new owner or its home government. Instead, the question was whether foreign ownership might afford the new owner’s government a platform for clandestine observation or disruption.

In such cases, national authorities could reject the proposed acquisition or they could impose conditions similar to those used for foreign takeovers involving classified technologies and materials — such as a requirement to set up separate compartmentalized divisions in which employees require home country citizenship and special security veting.As part of the process that led to the first CFIUS approval in the DPW case, for example, the Department of Homeland Security (DHs) negotiated a “letter of assurances” stipulating that DPW would operate all US facilities with US management; designate a corporate officer with DPW to serve as point of contract with DHS on all security matters; provide requested information to DHS when requested; and assist other US law enforcement agencies on all matters related to port security, including disclosing information as US agencies requested.

In the end, the public outcry against the DPW bid was sufficiently great that this mitigation agreement was dismissed out of hand, leading the parent company to withdraw its offer.

In the PotashCorp case, a Chinese or a Russian acquirer might have offered a higher price to shareholders than BHP Billiton or might have made more generous employment commitments, but this would not alter the national security calculation.

In considering how this “three threats” framework might be applied in Canada, one might begin by asking whether Canada’s national interests are best served by an international natural resource supply base that is as diversified and competitive as possible. Officials in Brazil and Australia occasionally resort to rhetoric and/or policy actions that might be better suited to a quasi-monopolistic resource producer, for example, with regard to exports of coal or iron ore. Does Canada prefer to adopt a similar stance as a quasi-monopolistic world supplier of, for example, energy or potash?

Looking more specifically at potential foreign acquisitions of Canadian companies in the extractive sector, the framework above would appear to fit Canadian circumstances quite appropriately (figure 1). While a complete analysis of the evolving structure of the international fertilizer industry is beyond the scope of this paper, the evidence suggests that supplies of potash and phosphates are becoming more concentrated (with the former centred in Canada and the latter centred in Morocco) as US sources diminish. Within this context, BHP Billiton’s hostile bid for Potash Corporation of Saskatchewan would have placed control of a major world source of supply in foreign hands rather than helping to expand, diversify and make more competitive the world supplier base.

Popular speculation at the time of the BHP Billiton bid for PotashCorp suggested that a Chinese or even a Russian firm might be an alternative to BHP. From a national security point of view, neither of these alternative acquirers would have been preferable to BHP, since in each case it would still mean transferring to an external actor control over a major source of supply in an increasingly concentrated industry.

It should be noted that the framework for evaluating implications of foreign acquisitions introduced here is directed at potential national security threats per se and excludes other considerations of “net benefit” as contained in the Investment Canada Act. Thus, in the PotashCorp case, a Chinese or a Russian acquirer might have offered a higher price to shareholders than BHP Billiton or might have made more generous employment commitments, but this would not alter the national security calculation.

Potential acquisitions of Canadian REE companies might be subjected to the same calculus as PotashCorp. A hypothetical Chinese acquisition of Avalon Rare Metals or Great Western Minerals Group would further consolidate control over the global REE industry. Indeed, Canadian authorities might want to be concerned about such consolidation even if a proposed Chinese acquisition did not involve a production site on Canadian soil. Again, as a purely hypothetical example, a proposed Chinese acquisition of Great Western Minerals Group’s operations at Steenkampskraal in South Africa would qualify, using the three threats framework, to be blocked by Canada on national security grounds.

In contrast to the PotashCorp case, two recent acquisitions by Chinese energy producers — PetroChina’s purchase of the undeveloped MacKay River project from Athabasca Oil Sands Corp., and Sinopec’s acquisition of Calgary-based Daylight Energy Ltd. — would appear, to the outside observer, to be helping to expand and diversify Canada’s energy base. While both PetroChina and Sinopec embody Chinese state ownership, this does not alter the national security calculus. Nor does the possibility that Chinese companies might be seeking access to oil sands production technology for use in China’s own oil sands, since doing so would potentially increase world energy supplies.

To be sure, there are valid reasons for subjecting SOEs to close scrutiny in cases involving foreign acquisitions. But it must also be acknowledged that ostensibly independent private investors in a relatively concentrated international industry can be subject to home country geopolitical pressures and directives. Thus the overriding question from a national security perspective is the structure of the international industry.

This brief review of how a new national security threat assessment apparatus might apply to sensitive cases in Canada should not divert attention from one of the principal benefits of such a rigorous framework — namely, to show that the vast majority of proposed foreign acquisitions pose no plausible threat. Application of this framework in Canada and elsewhere would help to dampen politicization of individual cases, enabling swift and confident approval of those acquisitions from which genuine national security threats are absent.

Photo: Shutterstock