The Gandalf Group conducts two major tracking programs of Canadian opinion. The C Suite Study, conducted for the Globe and Mail and BNN, and sponsored by KPMG, examines the opinions of Canada’s business leaders — the most senior executives of the top 1,000 companies. The Consumerology Study, for Bensimon Byrne, a Canadian advertising firm, looks at how megatrends or developments impact on consumer behaviour. Both of these research studies are quarterly, providing a time series overview of how the recession felt to Canadians and to their businesses.

The chronology that follows is based on tens of thousands of interviews with Canadians, and thousands of interviews with business leaders between 2008 and winter 2011.

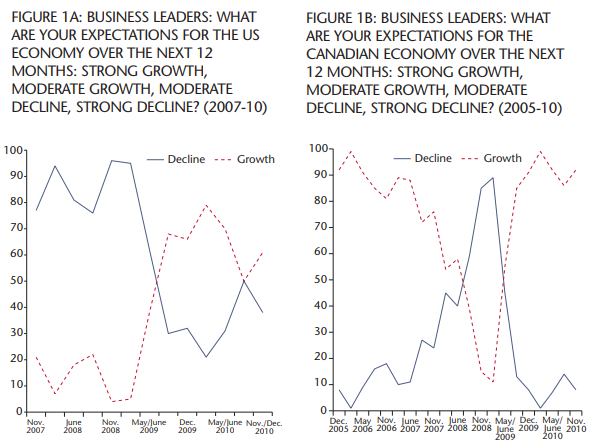

One of the more interesting things to track over the years has been how well executives understand and foresee the large economic trends that will affect them. On the big issues, they have been remarkably prescient. Their forecasts have tracked almost perfectly with the growth performance of the economy. As early as the beginning of 2007, Canadian executives saw weakness in the American economy. Well before there was any sense of a worldwide recession there was a large consensus among Canadian executive decision makers that the US was in decline (figures 1a, 1b).

In the last generation, with the demise of the corporate pension, all the responsibility for paying for retirement has devolved to the individual. The individual didn’t get the memo — very few Canadians have a level of savings or investments that would yield meaningful incomes in retirement. The crash in the stock market made that unavoidably clear for a lot of people. There is now broad support for government initiatives to provide more economic security in retirement.

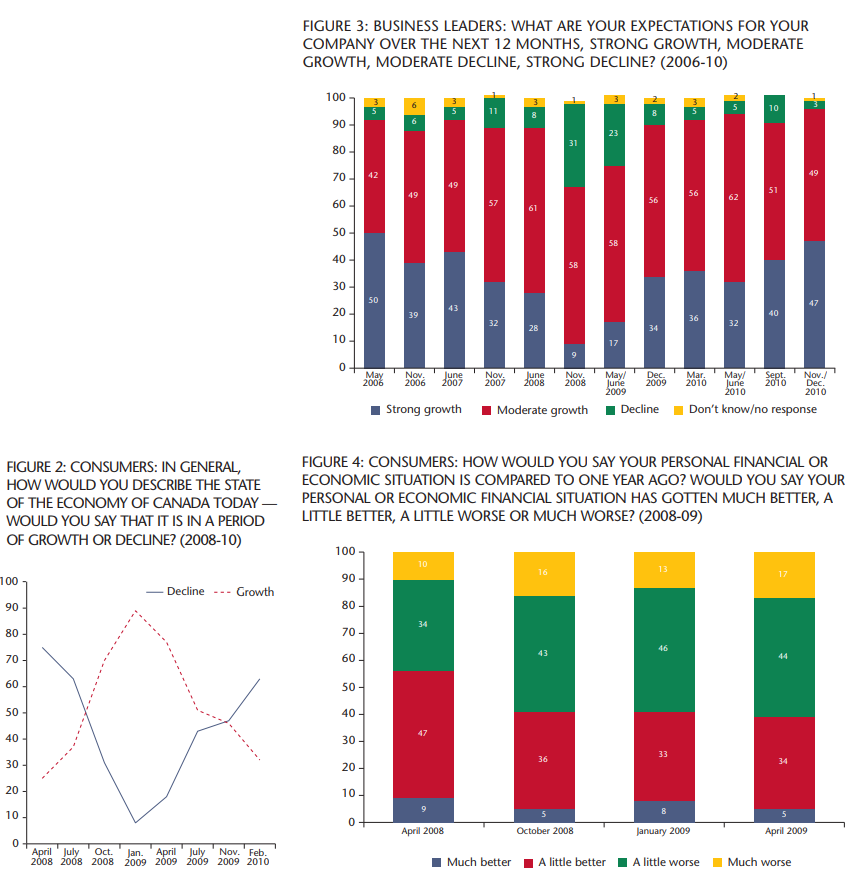

In that spring of 2008, while the business community was convinced there would be a major downturn in our economy, most Canadians were unaware of any potential economic disruption. Few recognized the rumblings from abroad until the fall of 2008. When the sense of crisis hit, there was no subtlety about it — that point in the fall of 2008 to the summer of 2009 represents the nadir of public sentiment about the economy. The deep pessimism one sees to this day among Americans never took hold here. Even during that brief but deep trough in the winter of 2008-09 when people were genuinely scared, few people expected the downturn to last long and most remained optimistic that the country would bounce back quickly (figure 2).

During this same period Canadian businesses stopped anticipating the recession and started to feel it. Most telling was that a large percentage of executives became pessimistic about the prospects for their own companies. Many companies in the manufacturing and service industries faced a large drop in demand for their goods and services, and many companies found themselves in a position they would describe as perverse. Their troubles stemmed from change in only one of their fundamentals — they could no longer access any money. No money was available in capital markets and, more devastatingly, credit was not being extended. Business leaders, especially resource companies, were very critical of what they saw as excessive tightening by banks (figure 3).

The recession did not affect Canadians as badly as it did the Americans. Canadians didn’t have to deal with the collapse in housing prices, and not as many lost their jobs. That is not to say that they were unscathed.

Let me provide one illustration. The analyses of multiple Consumerology studies has led us to conclude that nothing is a better predictor of consumer spending than whether consumers feel their personal finances have been improving or deteriorating. Conventional consumer confidence indexes measure consumers’ perceptions of the macroeconomic picture. Our research indicates those are not the primary drivers of opinion. If you are feeling poorer, you will tend to spend less money, regardless of how you feel the national economy is going to perform or what you read in the newspaper.

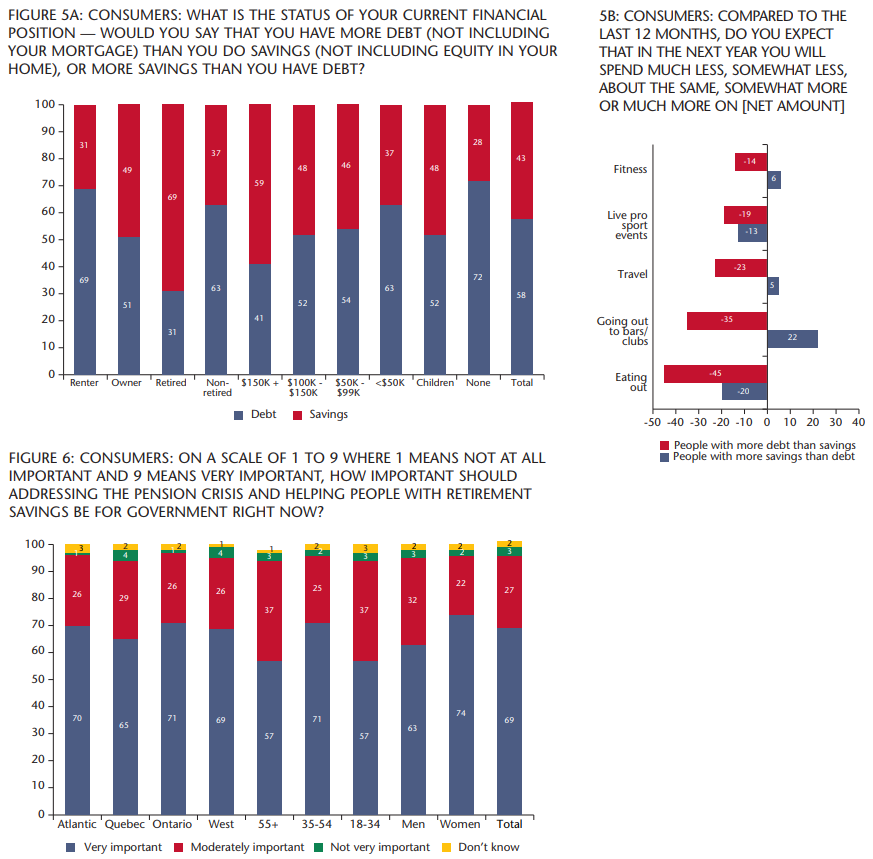

By April 2009, the percentage of Canadians who felt worse off was 17 points higher than one year earlier. At a full 60 percent of Canadians, it constituted a real drag on consumer spending. The exceptions were the affluent members of society, who were more able to absorb negative impact, and most of their losses were in investments, which began to recover more quickly than the job situation. The highest-income Canadians were least likely to have changed their spending much in the past few years. In other words, the stock market recovered before the job market did.

The middle class of the country encountered a major shock, and took on some new attitudes and behaviours that have endured to this point (figure 4).

One of the reasons that the recession was broadly traumatic is that people were vulnerable when the economic crisis hit.

The issue of personal debt has great prominence now, but Canadians, like their government, carried too much debt into the recession. This debt is built by people trying to live a lifestyle they cannot afford, aspiring to a standard of living the broad middle class can no longer afford, not if they are supposed to be saving for their retirement, their children’s education and a rainy day. Most Canadians are disappointed with their financial station in life and are compensating with credit.

Fully 60 percent of Canadians have more debt than savings, not including their houses and mortgages. This includes three-quarters of all parents with kids at home. These debtors are experiencing the recovery much differently than those without debt, which is creating two types of consumer. People without debt have been feeling the wind in their sails for the past year, and have been opening up their wallets and putting some frills back into their lives. People who hit the recession with debt are still cutting back, and are still unable to enjoy little luxuries like eating out once in a while or taking the family on vacation (figures 5a, 5b).

The fact that most people’s debt exceeds their savings is also partially indicative of the low level of savings most people have. In the last generation, with the demise of the corporate pension, all the responsibility for paying for retirement has devolved to the individual. The individual didn’t get the memo — very few Canadians have a level of savings or investments that would yield meaningful incomes in retirement. The crash in the stock market made this unavoidably clear for a lot of people. There is now broad support for government initiatives to provide more economic security in retirement (figure 6).

Canadians felt the economy was in recession for about a year and a half. By spring 2010, the vast majority of Canadians felt everything was moving in the right direction. Both consumers and business had positive but modest expectations. The modesty of the expectations is important. Most Canadians have diminished expectations. And most business leaders think that we are facing a long, tough slog to get out of recession, and they remain pessimistic about the US economy. One area where expectations are somewhat higher is about their own companies — the boundless optimism about their own prospects has returned.

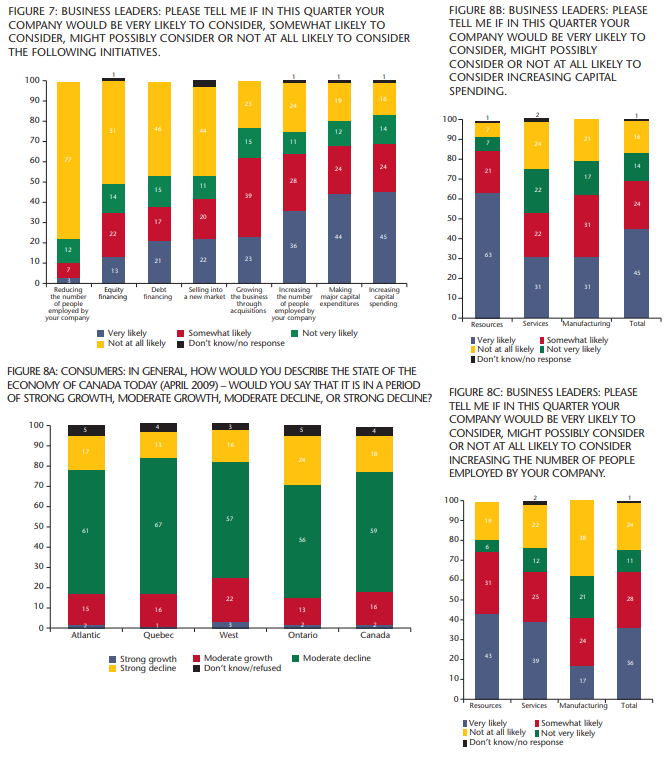

That optimism is reflected in their business plans. Over the next ear most businesses expect to be investing capital in their technology, their processes, and their scale. This is a year of hiring, not layoffs (figure 7).

Canada’s manufacturing sector is a big exception to even this humble narrative. Manufacturers have been largely excluded from the party. Too much of their competitive ability was based on a low Canadian dollar. As the dollar appreciated and approached parity with the American dollar, it left manufacturing companies exposed to their competitors, to the delight of resource executives. Some are investing in productivity enhancements to improve their competitive position, but others are not in a position to do so. The number of manufacturing companies in Canada continues to decline, and the sector’s prospects continue to lag those of other sectors.

One of the natural consequences of a struggling manufacturing sector and soaring commodity prices has been that the economy has felt very different, to both businesses and consumers, in western Canada than the rest of the country. At all points in the recession, western Canadians felt better about the economy and felt better about their personal finances. Leaders of western-based businesses are notably more positive than their central or eastern Canadian counterparts (figures 8a, 8b, 8c).

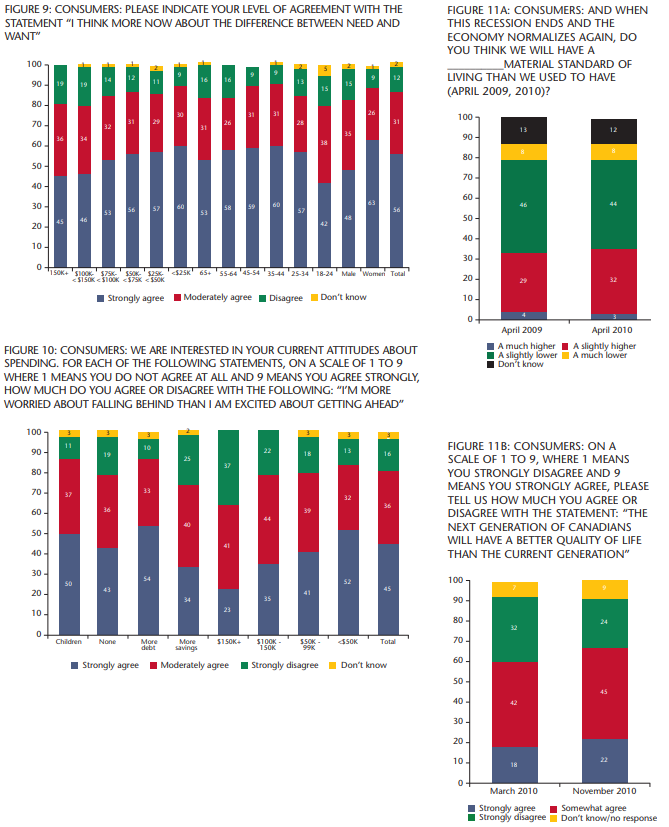

The recession left some clear imprints on the national psyche. A “culture of thrift” emerged that has consumers more frequently asking whether they need something or simply want it. That same culture made value the core purchase consideration, and resulted in massive shift away from brand names toward private-label or no-name products (figure 9).

Some behaviour from the recession endures as well. People are not eating out as much; they are looking at coupons and flyers more and buying fewer costly “green” products.

People have been left in a cautious, wary frame of mind. They are not sure they can trust the stock market, and are more likely to call themselves savers than investors. People are more worried about falling behind than excited about getting ahead (figure 10).

To conclude, Canada is headed in a direction where there is modest optimism about short-term personal financial prospects. Corporations are back to feeling strong optimism for their own companies and modest optimism for the economy. Canadians have felt the economy recover along with their own financial positions — yet for Canadians the recession underscored some key economic weaknesses for the individual — high debt loads and uncertain retirement income.

However, as Canadians look ahead, they are worried about the direction of the country. They feel that the economy that has emerged from this recession is a weaker one than what we went in with. Most of us think that the economy is on a trajectory to providing less opportunity and less prosperity in the future. Canadians have always operated on the assumption that every generation would have a better life than the previous one. That is no longer the case (figures 11a, 11b).

Somewhat likely Canadian business also sees a lot of challenges — structural government deficits, gaps between labour market needs and what is available, and the need to break into new markets to offset the continued decline of the US as both a market and a world power.

Canadians take some pride in the way the country weathered the worldwide crisis, and there is some relief that the worst is over. But we are left feeling more vulnerable than before, and some real fault lines in our economy and our society are opening up.

Photo: Shutterstock