Following massive recalls in 2010, consumer product safety has recently received a fillip in Canada. The Health Minister has announced new regulations governing cribs and cradles and aimed at decreasing the amount of lead that is allowed in consumer products. New legislation, the Canada Consumer Product Safety Act (CCPSA), has just been passed by Parliament and will come into force soon.

The CCPSA is important because dangerous products have recently raised serious concerns in Canada and around the world. A huge increase in recalls of tires, toothpaste, toys and pet food occurred in 2007, dubbed “the year of the recall.” Major product safety actions have continued since then, with recalls of melamine-tainted milk products in 2008; peanut butter and strollers in 2009; and cars, cribs, pharmaceuticals and Shrek-themed glasses in 2010.

The CCPSA is also important because of the changes in commerce that have occurred due to globalization of economic trade. In recent years, companies have spread their activities around the world in order to leverage low prices for inputs, such as raw material, components and labour. As a result of the changed commerce, defective products made by global supply chains have often caused trade-related tensions between nations. For example, in 2007, Western countries asked China to strengthen and enforce its own product safety standards, and the US proposed sending American regulators onto Chinese soil. China then retaliated by rejecting certain North American imports.

Following the many product recalls of 2007, governments in several countries increased their efforts to strengthen product safety regimes. For example, in 2008, Australian authorities implemented changes to their product safety systems, a one-stop-shop Web site, including clearing house to study emerging hazards and mandatory reporting of goods associated with serious injury or death. In the US, the Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act (CPSIA) was introduced in 2008 to supplement the Consumer Product Safety Act (CPSA), which was enacted in 1972. In Europe, RAPEX — a centralized coordinated system to ensure product safety — received a new thrust in investment and, as a result, was able to quadruple its recall activity in 2008.

The scarcity of resources devoted to consumer product safety affects Health Canada’s performance in multiple ways. First, Health Canada must increasingly depend on US regulators to ensure the safety of Canadian consumers; the majority of recalls issued by Health Canada are a result of the actions of the [US] CPSC.

Efforts aimed at strengthening the legislation in Canada started in earnest in 2007. After being shelved twice due to the calling of an election and prorogation of Parliament, the CCPSA was reintroduced for a third time as Bill C-36 in June, 2010. Following its passage in Parliament, the CCPSA received royal assent and will come into force on June 20, 2011. But can the new legislation achieve consumer product safety? And if not, what does Canada need to do to protect consumers from unsafe products? In order to answer these questions, it is important to consider consumer product safety in Canada, particularly by looking at the agency that is responsible for implementing the new Act and examining its performance in recent years.

Consumer product safety in Canada is the responsibility of Health Canada, the federal regulator of product safety and provider of health services. Health Canada’s program framework includes 4 strategic outcomes, 11 program activities and 42 subactivities. One of these 42 subactivities is the Consumer Product Safety program, which falls under the Consumer Products program. As a result of being housed under the Health Canada umbrella, Consumer Product Safety often gets overshadowed by other issues and must compete with other programs for resources. In contrast, other developed countries handle consumer product safety through independent and autonomous agencies that work as specialists in this area.

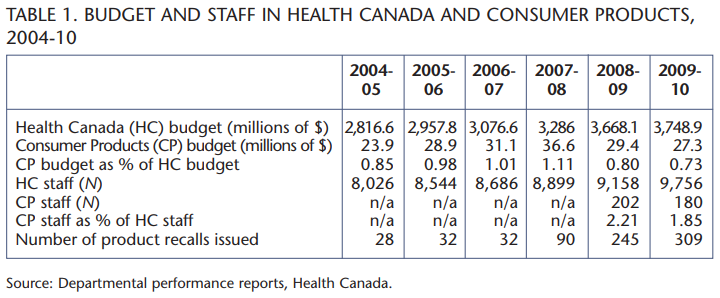

Each year, Health Canada allocates its budget for various program activities. In 2009-10, the organization spent an overall total of $3.75 billion, but the amount spent on Consumer Products was a mere $27.3 million. Of Health Canada’s 11 program activities, only two (Canadian Assisted Human Reproduction and International Health Affairs) had a budget smaller than that of Consumer Products. Furthermore, that $27.3 million had to be shared with the program’s two other subactivities, Cosmetics and Radiation-Emitting Devices. While specific allotment figures are not available for each category, it is safe to say that, in 2009-10, consumer product safety received a very small piece of the Health Canada pie. In addition to being one of the lowest-funded federal activities, Consumer Products has also experienced a decrease in its resources in recent years. As presented in table 1, the Health Canada budget has increased steadily since 2004, while the budget for Consumer Products has decreased sharply since 2007-08. Not surprisingly, the Consumer Products division cut 10 percent of its staff last year. In fact, as a percentage of Health Canada’s budget, Consumer Products’ budgetary share dropped to its historically lowest level in 2010.

Ironically, the sharp budget decrease for Consumer Products in 2007-08 coincided with several major product recalls, which raised some serious concerns about the effectiveness of Canada’s product safety net. This decline is even more troubling in light of the fact that several countries in the developed world increased the resources they devote to product safety during the same period. For example, the US government nearly doubled the Consumer Product Safety Commission’s (CPSC) budget during this timeframe — from $62.7 million in 2007 to $119.8 million in 2010. Further, the staff at the CPSC increased to 488 in 2010 from 393 in 2007.

In Canada, the decrease in resources occurred at a time of hectic activity on the product safety front. Health Canada issued a record 245 recalls in 2008-09, followed by another 309 in 2009-10. In fact, Health Canada has issued a total of 1,089 recalls since 1995, and of these, over three-quarters (836 recalls) were issued since 2008, i.e., in the same period when the Consumer Products program witnessed cuts to its funding and to its staff.

The scarcity of resources devoted to consumer product safety affects Health Canada’s performance in multiple ways.

First, Health Canada must increasingly depend on US regulators to ensure the safety of Canadian consumers; the majority of recalls issued by Health Canada are a result of the actions of the US CPSC. Second, Health Canada’s performance related to consumer product safety remains inadequate and irregular. For example, the number of subscriptions to Canada’s consumer product safety recall Web site stood at 7,844 in 2009-10, while the same figure for the US CPSC stood at 308,000. Even if we consider that the population of Canada is about 10 percent of that of the US, clearly the Canadian figure of 7,844 is significantly lower than the 30,800 (10 percent of the US figure) it should be. In addition, the CPSC makes use of a number of social media avenues to reach out to consumers, and Health Canada’s efforts to reach consumers pale in comparison.

Another indication of Health Canada’s poor performance on the consumer product safety front is reflected in the fact that the organization has not made significant use of the powers within its scope. For example, companies that violate the provisions of the Hazardous Products Act can be fined to the tune of $1 million; however, Health Canada has not reported the imposition of any penalties or the initiation of any proceedings against companies that have violated these laws. In contrast, the US CPSC has imposed 60 penalties in the last two years and has collected over US$13.7 million in fines. A number of these fines were related to recalls issued during 2007 for excess lead in toys and other products. Although selling products with excess lead is a violation of Canada’s Hazardous Products Act, no company has been fined in this country.

In short, the resources allocated to consumer product safety in Canada are inadequate and have dwindled at a time when other developed countries have increased spending in this area. Further, Health Canada does not appear to have made reasonable use of its existing powers. Given this situation, it is necessary to revamp the Health Canada structure, in addition to strengthening legislative measures. Unfortunately, the CCPSA does not move things in this direction.

The CCPSA has a number of features that bolster consumer product safety by providing more authority to Health Canada, and certainly this Act is an improvement over the 40-year-old legislation (Hazardous Products Act) it will replace. Of particular note, the CCPSA mandates companies to report to Health Canada about any actual or potential dangers their products might pose to consumers. Further, it empowers Health Canada to inspect consumer products, issue recalls and penalize companies that violate the provisions of the Act. But, on their own, these measures are not enough to ensure consumer product safety in Canada. Apart from a few new additions, the CCPSA falls short on a number of provisions in comparison to its American counterpart. First, the US legislation provides several measures to ensure that information related to harmful products does in fact reach the CPSC, including the establishment of a consumer product safety database that citizens can access and use to report product-harm incidents. Further, the US legislation provides protection to whistleblowers so that information can reach the CPSC even when the top management of the offending company is not ready to share it.

Second, the Canadian legislation provides extensive powers to inspectors, allowing them to test products being sold in stores. Not only is this a resource-intensive exercise that has raised concerns about privacy, but it is also ineffective because one can never have enough inspectors. The best way to achieve product safety is to ensure that the products do not reach the market in the first place. Toward this end, the American legislation mandates third-party testing of toys and children’s products. Unfortunately for Canadians, the CCPSA does not do the same.

Third, while the actual issuing of a recall certainly stands as an important first step in the world of product safety, recovery of the defective products from the hands of the consumers is even more important; however, the CCPSA does not take any steps in this direction. In contrast, US legislation mandates tracking labels or consumer registration of children’s products to ensure easy and efficient recovery in the event of a recall.

Finally, the most fundamental difference is that the US legislation aims to strengthen not only the regulation but also the regulator, i.e., the CPSC. Evidence of this goal can be seen in the fact that the CPSC’s budget doubled over a period of seven years. Also, the CPSC was made truly independent and accountable through a ban on industry-sponsored travel and other such activities. Meanwhile, in Canada, the CCPSA focuses on regulation while leaving the issues of reform and funding to the discretion of the health minister and Health Canada. If the past is any indication, then a lack of federal resources and a lack of will to exercise federal power will continue to impede consumer safety in Canada.

The CCPSA takes a number of necessary steps toward ensuring consumer product safety in Canada. It mandates that companies must provide product-hazard information to Health Canada, and it gives that organization the “teeth” to issue and enforce recalls, even when a company is not ready to cooperate. Certainly this change in legislation grants some essential powers to Health Canada, powers it has long needed. While the new Act is laudable, it does not make full use of the opportunity to strengthen our product safety regime in Canada. It does make it easy to identify harmful products being sold in the market and, in turn, to take action against them, but it does not take adequate steps to prevent these products from reaching the market in the first place. Rather than generating useful product information from multiple parties, Canada continues to rely on companies that have already shown an increasing reluctance to provide such information of their own volition. Further, the CCPSA does not take steps to provide resources to Health Canada and to reform the struggling Consumer Products program so that it can use the teeth that it has been given.

Given the decrease in resources for consumer product safety in recent years, it is only reasonable to express concern about the kinds of resources that will be available to implement the provisions of the CCPSA. Furthermore, since Health Canada has not shown a propensity in the past to use its powers to promote active change, there is every reason to doubt that consumer safety will actually improve following the enactment of the CCPSA.

Photo: Shutterstock

The authors would like to thank the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, whose generous grants helped them to conduct and communicate this research.