Will the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) rise from the dead? It’s a question that will preoccupy Canadian officials as they sit down at the table this summer with the US and Mexico to discuss revising NAFTA. In mid-July, negotiators for the 11 remaining TPP countries (the US withdrew in January) agreed at a meeting in Japan to try and create a new framework for the deal and keep it alive (an effort sometimes called “TPP 2.0” or “TPP Minus One”). Under its current format, the TPP cannot exist without the participation of the United States. The negotiators are expected to meet again late this summer, ahead of the APEC Economic Leaders’ Meeting in Vietnam in November.

In an earlier meeting in Chile in March 2017, the original TPP-11 countries were also accompanied by representatives from China, Colombia and South Korea. The attendance by 15 Pacific Rim nations in Chile signalled a consensus across the Asia-Pacific region that free trade and regional integration are effective ways to stimulate the exchange of goods and investment. Moreover, the high standards for modern trade rules (in areas such as energy and e-commerce) and the labour, environmental and intellectual property protection clauses within the TPP are perceived as considerably upgrading the less comprehensive pacts between pairs of TPP countries, including the 22-year-old NAFTA.

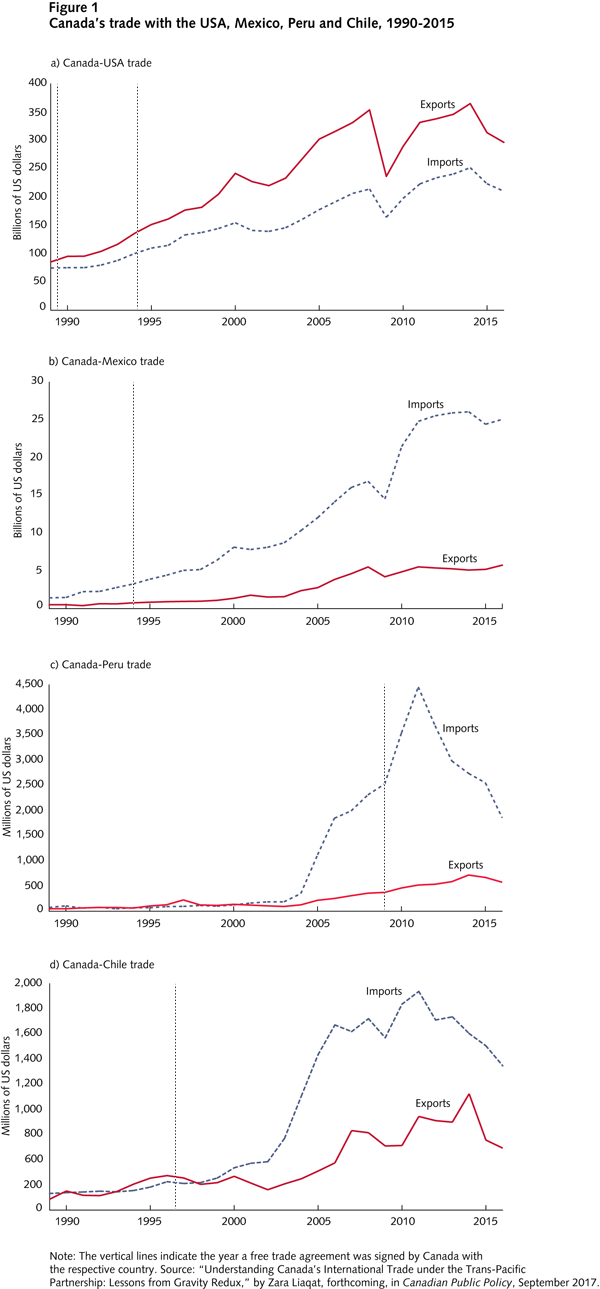

A concern raised by some TPP opponents in Canada is that the volume of Canadian imports exceeds exports for many TPP member countries, and if brought into force, the TPP could worsen trade imbalances between Canada and these countries. According to one study, the removal of tariffs in the TPP would possibly exacerbate Canada’s growing trade deficit with the region, since more of the products Canada imports from TPP member nations would become tariff-free than the products that Canada exports to these countries. Such trends have been observed in the case of Mexico following the endorsement of NAFTA in 1994, and also upon the enactment of the Canada-Chile Free Trade Agreement (FTA) in 1997 and the Canada-Peru FTA in 2009. A glimpse of the evolution of Canada’s trade flows with various countries reveals a remarkable surge in trade upon the implementation of the Canada-US FTA in 1989, later superseded by NAFTA in 1994 (figure 1a-d).

The small share of Canada’s global trade constituted by some of the TPP-11 countries is worth highlighting. Apart from Mexico and Japan, which accounted for 3.3 percent and 2.3 percent, respectively, of Canada’s total trade of goods in the year 2014, each of the other member countries captured less than 0.4 percent of Canada’s merchandise trade.

The criticism that the TPP gives an unfair competitive advantage to countries with lower wages may be overstated, since some of those countries already enjoy nearly duty-free access to Canadian consumers and firms. These include countries such as Mexico, Chile and Peru. Although TPP membership may trigger some trade movement away from Canadian commodities toward Asian ones, some of these countries might still be able to steal a part of Canada’s market share if Canada decides not to be a party to TPP 2.0. In fact, the shortfall could be rendered moot by greater access to new markets. In light of lost opportunities to augment trade relations in emerging markets and the wearing down of Canada’s preferential market position within NAFTA, many economists and policy analysts in Canada have recommended signing the agreement.

A key objective of signing a free trade deal is clearly to reduce trade costs. These costs include those which may be obvious, such as tariffs and transportation costs, but also sometimes include others that are harder to observe (exchange rate risk, for example). In many cases, expanded trade flows can be explained by falling trade costs. However, there are several other sources of trade growth highlighted in the literature. For instance, higher economic growth in either trading partner can stimulate trade between them. Similarly, increasing income similarity between two countries may also induce them to trade more.

My forthcoming study, to be published in Canadian Public Policy in September, shows that much of the growth of Canada’s trade with the TPP-11 countries is linked to output expansion (a growing GDP) in these countries. The only exceptions are Vietnam, Brunei Darussalam and the three countries with which a free trade agreement is already in force (i.e., Chile, Mexico and Peru). Because trade restrictions diminished after putting into effect a free trade agreement, lower trade costs accounted for about 27 percent of the growth of bilateral trade flow between Canada and Chile; the corresponding figures are over 20 percent for Mexico and over 50 percent for Peru. Such results suggest that expanding Canada’s international linkages will depend on its participation in major proposed trading networks, such as the TPP, or effective ongoing bilateral free trade agreement negotiations with various Pacific Rim countries, including Japan and Singapore.

Nevertheless, trade is much more complex than the aggregate data imply. Every day, Canada and its trade partners exchange hundreds of different goods, and economic analyses of trade that are based on aggregate data instead of individual product groups must be viewed with caution. Workers in specific industries or with skill shortages may experience serious transition costs. For instance, eliminating tariffs on Japanese vehicles might erode domestic demand within the local auto-parts manufacturing industry. A deeper look at the industry level is needed to identify sectors most likely to suffer as a result of the TPP, and also to identify where Canada’s comparative advantage truly lies.

A detailed account of Canadian tariffs on imports from the TPP member countries is necessary for a comprehensive assessment of projected changes in patterns of imports of foreign raw materials. The effect of any free trade agreement is to divert trade away from non-members toward members, with tangible losses for China, India, Thailand and South Korea in the case of TPP-11. In fact, it is for that reason that both China and South Korea have expressed interest in becoming a party to a trans-Pacific trade deal, marked by their presence at the trade talks held in Chile in March 2017.

The United States has shown an interest in negotiating individual bilateral agreements with some countries, particularly Japan. The resulting outcome is complex for Canada and the countries that already have bilateral trade deals with the United States. Given that Japan has ratified the original deal, along with New Zealand, Canada’s participation in TPP 2.0 would be preferable to the conceivable alternative of a multilateral agreement from which Canada is excluded; TPP 2.0 can grant Canadian firms relatively unfettered access to the trans-Pacific countries.

This article is part of the Trade Policy for Uncertain Times special feature.

Photo: Chile’s Foreign Minister Heraldo Muñoz, centre, speaks during a press conference after the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) meeting in Viña del Mar, Chile, in March 2017. (AP Photo/Esteban Felix)

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.