An average paper in a peer-reviewed academic journal is read by no more than 10 people, according to Singapore-based academic Asit Biswas and Oxford researcher Julian Kirchherr, in their controversial commentary “Prof, No One Is Reading You,” which went viral last year. They cite some remarkable statistics: as many as 1.5 million peer-reviewed articles are published annually, with as many as 82 percent never cited once, not even by other academics.

In other words, most academic writing rarely influences thinking beyond the privileged circles in which it is constructed – and the vast majority of it is far from influencing public policy and debate on critical issues.

Other academics challenge such dire statistics and use different approaches to shore up the numbers, such as changing what counts as a citation (including self-citations and non-academic citations) and using a longer window to check for citations of their work.

Dahlia Remler, on the London School of Economics blog, casts doubt on the damning figures in her article “Are 90 Percent of Academic Papers Really Never Cited?” She notes that citation rates actually vary widely by field. Still she acknowledges that as many as one third of social sciences articles go uncited, 82 percent for the humanities and 27 percent for the natural sciences. What started out as a skeptical rejoinder ends with a simple plea: “Academic publication needs fixing.”

Lest the sciences think they come out looking good here by comparison, evidence from other quarters is not so favourable. Twenty years ago, the journal Science found a mere 45 percent of articles published in the top 4,500 science journals were cited within five years. A more recent study found a decline in that figure: only 40.6 percent of articles in the top science and social science journals were cited within five years.

In other words, the problem is not a new one and appears to be worsening. Why? There’s simply too much to read.

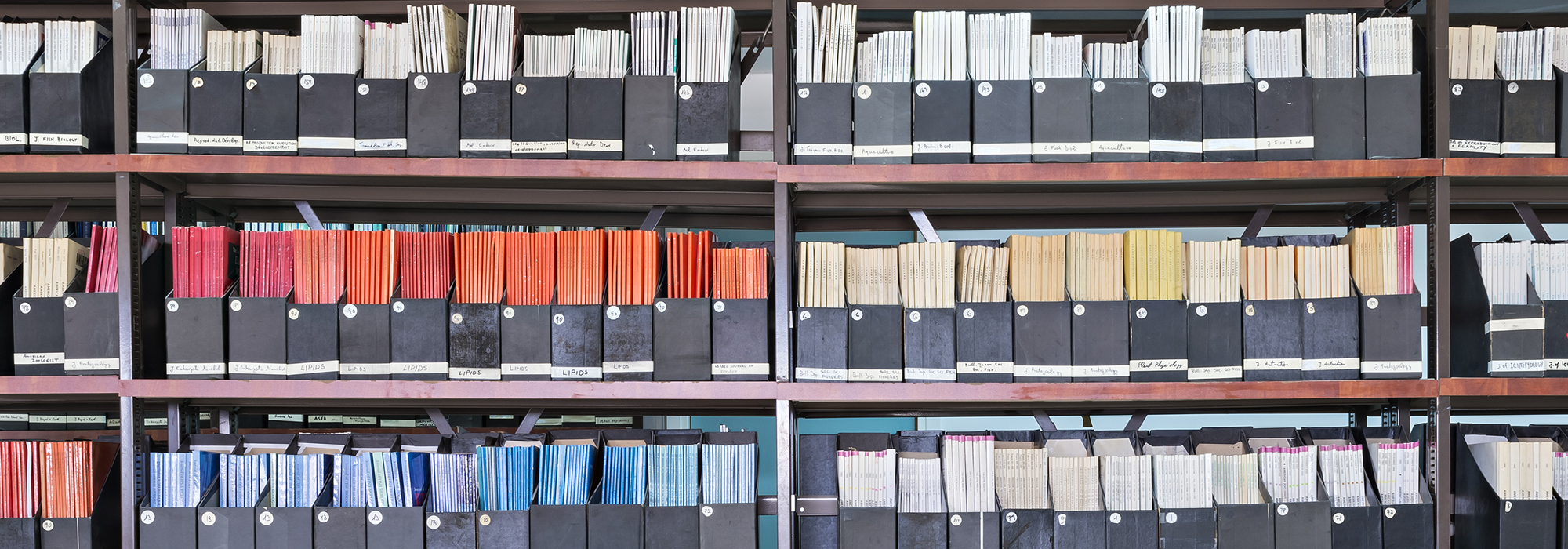

We are awash in a sea of unread journal articles

There has been a dramatic growth in the number of journals and, by extension, journal articles published every year. An STM Report from 2015 notes there are more than 28,000 active scholarly peer-reviewed English-language journals, which publish around 2.5 million articles annually. The report notes the number of journals is growing at a rate of at least 3.5 percent per year; this reflects a growth in researchers of about 3 percent per year.

Growth in the number of academic journals is possibly also linked to their surprisingly high profitability, as well as to the counter-movement to create open-access journals. To put these growth numbers another way: the rate of journal article output more than doubles every 20 years, notes the Chronicle of Higher Education. And those are the optimistic numbers. Another study pegs journal article growth at an average 6.3 percent per year.

The result? A trend toward more papers garnering fewer citations.

It’s not bad news for everyone, as it turns out – just for most. As the number of journal articles increases, the number of citations on average per article decreases. The STM Report, however, notes that the distribution of citations is highly uneven, with 80 percent of citations coming from fewer than 20 percent of articles. As one researcher summarized the trend: “Fewer journals and articles [are] cited, and more of the citations [are] to fewer journals and articles.”

In other words, the deluge of uncited papers is punctuated by a handful that rise to the surface, like the tip of an iceberg. But lest you get the impression the established journals are the ones benefiting here, the trend is just the reverse. The dominating influence of elite journals may be on the way out. It turns out the number of highly cited papers published in highly cited journals is on the decline, while the number of highly cited papers coming from new and less established journals rises steadily.

There are any number of mitigating factors for why we have so many unread journal articles: the publish-or-perish mantra that seems to kick in earlier with each generation of scholars, the parsing of a study into many component parts to maximize journal article output, an academic system that rewards researchers for output and not necessarily influence, to name a few. No change will occur unless, as one commentary notes, “the system of rewards is changed.”

But not least, part of the blame is surely the result of a system that looks down upon or at least disregards academic engagement with media, policy-makers and the wider world it claims to address. The truth is, few beyond the academy know or read academic journals.

Incentivizing academics to engage with the media

It would be a small – but critical – step for academics to tell audiences why their research matters. Presumably much of the research in journal articles would and should matter to those beyond academic circles, particularly those who are in the business of creating policy.

Biswas and Kirchherr in their article propose just such an approach. The answer to researchers being trapped in the echo chamber of academic journals, they suggest, is to step beyond them – and engage the mainstream media: “If academics want to have an impact on policymakers and practitioners, they must consider popular media, which has been ignored by them.” This is not a refutation of journal publication or the important evidence it imparts, but an extension of the publication process.

So why is this not happening already – at least not frequently?

An article in SciLogs puts it this way: “The biggest hurdle is that academia has yet to find an incentive for them to take time away from the lab to engage the public. Universities still operate under an ancient system that values only scholarly output.”

Academic physician Daniel Cabrera calls for a change in the way traditional journal citation “impact factors” are used for academic promotion. He suggests instead that we establish a system that also rewards academics who engage and share their knowledge with the public via traditional, new and social media too. Journals and citation counts are no longer enough.

Cabrera points to the many publicly available and robust metrics now available from media and social media. The time has come, he suggests, for academics to engage beyond journal articles and communicate their evidence and ideas to a broader interested public.

By no means are these calls for academic engagement with the media – and beyond – isolated. It’s become somewhat of a clarion call.

Last year, the Guardian published a commentary entitled “Academics: Leave Your Ivory Towers and Pitch Your Work to the Media.” Kristal Brent Zook, an academic herself but also a journalist, says she’s wondered why her academic colleagues don’t engage or write for the media more often: “Why don’t we hear more from the doctors behind the data?” So she asked around. The answers she got from a survey of academics surprised her.

It turns out the main reason is fear. According to Zook, academics don’t engage with the media because of fear of the unknown – both of the media and how it works, and of engaging with the general public. There’s also an unspoken wariness or, at worst, hostility between academics and journalists who have differing cultures, timelines and agendas.

However, according to Sense About Science USA, the journalist’s door is (almost) always open. It recently published new media guides for scientists and surveyed more than 200 journalists in the process. It found 92 percent of journalists are always open to scientists calling them if they have information; 94 percent of journalists said they want to hear from sources if they feel they were misquoted or misrepresented; and 94 percent always or most of the time read the academic articles in question before contacting the scientists for interviews about their research.

What happens when academics step outside the journal echo chamber?

In her commentary, Zook notes the positive outcomes that arise when academics do engage the media. One academic said that one of her posts went viral, ended up on numerous syllabuses and opened up opportunities to write academic articles, book chapters and even a book; and it led, indirectly, to a grant. “It was a catalyst,” she said. Another highlighted how writing for the media made her a better writer. She realized how riddled her writing was with jargon and that these big words were often a crutch. “I have to cut through the bullshit and just say what I really mean.”

Duncan Green, for the London School of Economics Impact blog, emphasizes that much of academic life is “spent within the hallowed paywalls of academic journals,” but he says academics could and should engage more with new and social media to attract audiences to their research.

A Wall Street Journal article headlined “Why the Dean of Harvard Medical School Tweets” similarly outlines how successful engagement strategies – in this case, using Twitter – can make academic research meaningful beyond the academy and can reach other educators, policy-makers, economists and politicos, with important outcomes. Harnessing traditional and new media to engage with wider audiences helps make the research live on, in other contexts, and affect change.

How the public reaps the rewards of academic engagement

So engaging the public through traditional and new media is good for academic uptake in a wide range of ways, but it turns out it’s also good for the general public. According to Deepti Pradhan, only 2 percent of citizens in the US are actively and formally learning about science; the rest learn about science “through the general media.” Quality evidence in media outlets can help shape public perceptions and public debate on important policy issues. The lack of it can sometimes have devastating consequences.

Declining vaccination rates are a good example. In a study last year, 60 autism scientists were polled about the importance of communicating their work to the public. Fifty-nine felt their research would be of interest, yet less than half felt it was “very important” for them to communicate – in other words, they felt it wasn’t their job. Half felt they didn’t have opportunities to communicate with the public, and half felt they didn’t have the time to do so.

But the study authors emphasize the outcome of just such a lack of engagement. They note that the field of autism is riddled with misinformation that is reaching the parents and caregivers of kids with autism. This has real-world consequences, not least of which are the all too frequently repeated myths around the harms of vaccinations (namely, that they cause autism – substantial evidence says they don’t), which directly affect rates of vaccination in the population.

The evidence is there, and it’s good, but it’s not getting to the public. The lack of communication between scientific researchers and the public “threatens the relationship with the community they’re trying to help,” claims an editorial from the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative.

The challenge for many academics is that even if they want to engage in such public discussions – to go where the audiences already are, in traditional, new and social media – they don’t often know how to go about it, and few have the time or the resources to do it properly.

How 700 words can make a difference

It was in just such a context that EvidenceNetwork.ca was born in Canada. The founders, academics Noralou Roos and Sharon Manson Singer, were frustrated that research they knew well in the field of Canadian health policy seemed only rarely to make it into the mainstream media. There were a few notable exceptions, articles produced by the handful of remaining well-trained health journalists scattered across the country. On the whole, they found the media discussion dominated by hyperbolic language from left- and right-wing think tanks and political parties. The extremes got airtime, but most of the nuance and depth of any research was lost.

Roos and Manson Singer wanted to inject more evidence into the discussions and to see the rich world of academic research given equal airtime. So they created EvidenceNetwork.ca, with a sizable grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Research Manitoba, to create a bridge between the world of academia and the world of journalism.

In consultation with our academic experts, we discovered that academics often worry they’ll lose control of the message and of the way their research is represented in the media in traditional interview formats. At the same time, we learned from our media advisers that academics often fail to heed the tone, style of language and breadth of discussion permitted in submissions to media outlets.

From this tension was born the idea to help our academic partners craft op-eds, the opinion-based commentaries that appear in most media outlets. Op-eds frequently influence politicians, policy-makers and other decision-makers, and are a popularly read media genre where studies and evidence come to the fore.

We adopted a slightly different model with the idea that academics can’t be all things to all people. They can’t be expected to know the media environment inside out or have the time or interest to develop relationships directly with journalists and editors. So we decided to do that for them. What started out as an experiment in 2011 has blossomed into a full media service for academics and a clearing house of high-quality, original health policy articles ready for publication for media outlets.

EvidenceNetwork.ca acts as a mediator and editorial service for academics. They are asked to write a rough draft of their op-ed. We guide them on how to proceed with the first draft – the dos and don’ts of the process. After that, we take it from there. Our editorial team works on tightening up the op-ed, with the needs of specific media outlets in mind. Rough drafts are often trimmed to specific word counts, the argument is tightened and jargon-laced language is excised in favour of plain or conversational language suiting traditional op-ed style.

The author is part of this process throughout. The op-ed routinely goes through three or more rounds of edits, and if the material is controversial or political in any way, it goes through an informal peer review process with other experts vetting the piece for balance and accuracy. All points of evidence are hyperlinked to their sources. Once we are certain the piece is ready for the media, we secure author approval, and then EvidenceNetwork.ca shops the op-ed to the major media outlets on behalf of the author.

We have robust data to prove it works. In the last year alone, we edited and placed over 100 op-eds. Almost four dozen were published in the top five media outlets alone (Globe and Mail, National Post, Toronto Star, La Presse and Le Devoir) in a single year; 191 more were published in the bigger-city media outlets and 665 in the smaller regional media in 2015. Year over year we’ve improved these metrics. In total, we’ve published 494 op-eds garnering more than 2,000 media publications in fewer than five years, publishing in everything from the biggest media outlets to the smallest niche and rural papers across the country.

Our op-ed writers, as a result of their op-eds, have been cited by ministers and invited to parliamentary hearings, committees and briefings, at the federal and provincial levels. Our pieces have kicked off other media investigations, editorials and interviews for our writers – in print, online, on radio and TV – and several of our writers have won academic engagement awards from their more forward-thinking universities for their efforts. How much of the research documented in the op-eds has been picked up and used in political, policy and other circles is harder to measure – but we know at the very least that the research is getting out there and not just sitting in academic journals.

The beginnings of a global movement

We hope that the bridge we’ve helped build between mainstream media and academic research sets a precedent for further exchanges and participation between these two distinct groups. We also hope that our op-ed model will be copied and replicated by others elsewhere.

EvidenceNetwork.ca is by no means the first. There have been other successful models for helping academics to showcase their research to mainstream audiences. There is Project Syndicate, based in Prague and New York, which provides professionally edited and copy-ready commentaries authored by academics to global publications on a subscriber model (the media outlets subscribe to the paid service for content on a sliding scale). It boasts that 476 media outlets in 154 countries carry its content.

The United States, the United Kingdom and Australia each have their own editions of The Conversation, a quality content provider that uses professional journalists to collaborate with academics and translate academic research into evidence-based news articles and commentaries. It puts a Creative Commons stamp on all its content so it is available free of charge, and it partners with a variety of media outlets to push its content out globally. Its funding comes from a wide range of university partners and foundations.

Some high-profile think tanks, such as the Institute for Research on Public Policy, have also been successfully translating policy-based research to multiple audiences through esteemed publications like the IRPP’s Policy Options for decades.

Canada also has the Science Media Centre of Canada, which does not provide content directly to media but connects journalists with academic experts and organizes webinars and media backgrounders on complex research. It also shares forthcoming academic articles with journalists in an effort to increase coverage of science issues. It is funded by the public, private and not-for-profit sectors, but it mandates that no more than 10 percent of funding comes from any single source so it can maintain its independence.

Both Canada and the United States also have media projects to get more women’s voices into the media. Canada’s Informed Opinions offers op-ed writing workshops in university and NGO settings across the country and offers strategic advice to get more women to both write for and be interviewed by the media. Its fun tag line and comic graphic, “What if I really am the best person?” sums up the hesitation too many academic women feel before they wade into media waters and stake their claim as the experts they are. Founder Shari Graydon has also done original research on the underrepresentation of women as sources in Canadian media stories. Unfortunately, despite much awareness about this issue in recent years, the statistics haven’t budged in a couple of decades, with women being quoted on average in 21 percent of news stories. Op-eds offer a unique way for women to control their voice and message and still push their expertise out to wider audiences.

It’s about time for a global movement that pushes academic evidence out into the world in an accessible format so that it does not sit idle behind journal paywalls but makes a difference in the world in which we live.

We all benefit when research is read widely and discussed soundly. It’s how we can make sure evidence matters.

This essay is adapted from the forthcoming e-book Why We Need More Canadian Health Policy in the Media, edited by Noralou Roos, Kathleen O’Grady, Eileen Boriskewich, Mélanie Meloche-Holubowski, Carolyn Shimmin, Kristy Wittmeier and Nanci Armstrong, which will be available on Kindle, Apple, Google and other formats.

Photo: Sergei25/Shutterstock.com

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.