The under-resourced Civilian Review and Complaints Commission for the RCMP did a valiant job in substantiating the discriminatory treatment of a Cree mother grieving the killing of her son. In its final and interim reports, the commission also raised a number of questions about how the investigation into 22-year-old Colten Boushie’s death was handled by police.

Still, the commission’s recommendations for improvements, including for cultural awareness training of officers, were not terribly ambitious. Indeed, the RCMP in Saskatchewan was able quickly to respond that all of its recommendations would soon be implemented. Much more reform of the RCMP is, however, required to improve its relations with Indigenous peoples and respond to systemic discrimination against them. These reforms need to go far beyond cultural awareness. They should attempt to change the very culture and governance of the RCMP.

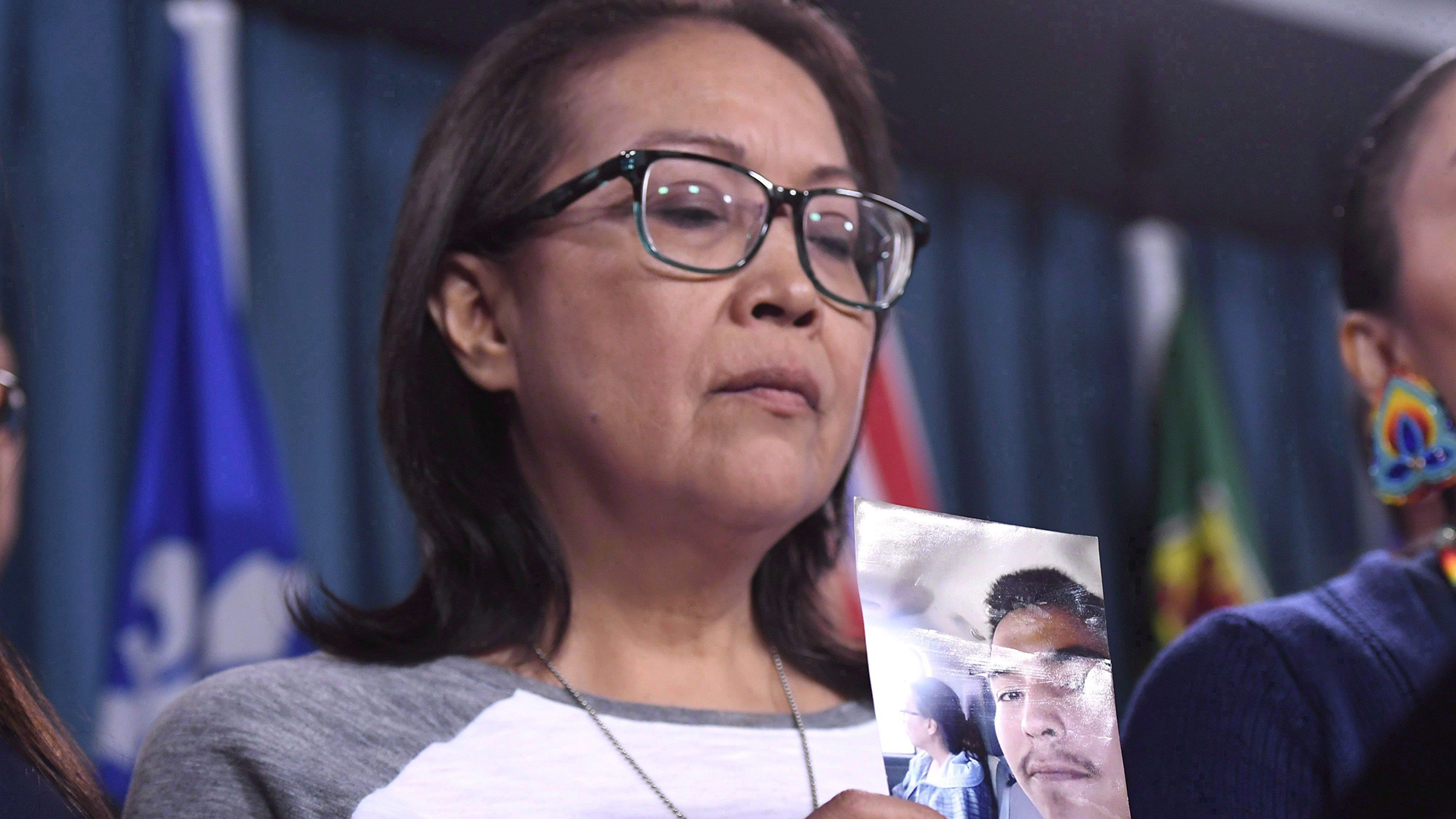

Boushie, from the Red Pheasant Cree Nation, was fatally shot by Saskatchewan farmer Gerald Stanley in 2016. Stanley was subsequently acquitted of murder and manslaughter by an all-white jury who apparently accepted the defence’s portrayal of the shot in the back of Boushie’s head as accidental. The commission’s findings that the RCMP acted in a discriminatory manner when they asked Boushie’s mother, Debbie Baptiste, whether she had been drinking, have rightly sparked outrage, making headlines both in Canada and internationally.

The commission concluded that Boushie did not commit any property crime even though property crime was stressed in the RCMP’s first two news releases and Stanley’s murder charge not mentioned until the third news release. The commission also found the RCMP made a “significant error” when they did not preserve the blood spatter evidence inside the car in which Boushie died, allowing the blood to be washed away.

These findings are important. They have been well publicized and the vast majority accepted by the RCMP. Yet there were a number of troubling omissions in the commission’s reports and reactions by the RCMP commissioner and the RCMP’s new union, that suggests more fundamental change is necessary. These areas ripe for change include:

• Persistent stereotypes that Indigenous people are dangerous

The RCMP sent seven officers with carbines and a police dog to inform Baptiste of her son’s death, and to search for one of four other people who had been in the car with Boushie – a man referred to as “C.C.” in the commission report. RCMP Commissioner Brenda Lucki rejected the commission’s findings that the Mounties’ heavy response to the Baptiste home was unreasonable. She argued that the courts had already ruled that police have the right to protect themselves from danger, even if there is a low risk of weapons being present. She was referring to a Supreme Court decision that held that a dynamic entry into a house associated with a violent gang with a warrant was justified.

But was potential danger ever legitimately verified and communicated? Stanley’s son had told the RCMP that two of the four Indigenous persons who fled the farm (after Stanley had discharged his pistol) were armed – including C.C. But according to the commission, not all the officers involved in the tactical approach on Baptiste’s home were aware of what Stanley’s son had claimed. Officers did not ask a neighbouring farmer, who told them he had driven C.C. back to the reserve, whether C.C. was armed. And when officers went to the homes of the grandmother and mother of C.C. – places he was most likely to be – they did not use the heavy-handed approach they had used with Baptiste.

All of this makes Lucki’s refusal to accept that the RCMP acted unreasonably in surrounding the house with guns drawn, lights shining and a police dog at hand difficult to accept. Combined with the comments that the National Police Federation has made that the commission had overlooked evidence of the “Boushie group’s intentions,” suggests that the RCMP may still view Indigenous people as dangerous even when they are not.

• A blue-wall of silence

The commission was unable to identify which officers made inquiries about whether Baptiste had been drinking, smelling her breath and allegedly telling her to “get it together.” Its investigators asked police, but were told that officers didn’t recall the comment, hadn’t heard it, or denied it was ever uttered. This speaks volumes about the oft-observed blue-wall of silence and solidarity within police forces.

Without identification of the individuals responsible, disciplinary action will not be taken. In any event, the RCMP needs to move from a para-military model of discipline to a more transparent form of discipline, similar to that used for other highly paid professionals. People who engage in discriminatory conduct in the private sector are often quickly fired – this has never been the case with the RCMP.

• Discriminatory justice

The commission found no discrimination in the tactical approach the RCMP took when approaching the Baptiste home; no discrimination in the RCMP’s arrest and overnight detention of three Indigenous people who were in the car with Boushie and were apprehended even before Stanley was; and no discrimination in the failure to secure and preserve the blood spatter evidence in the car from the heavy and expected rains that fell the night Boushie died.

Equality, however, is a comparative concept. The Indigenous witnesses were treated more harshly by the RCMP than Stanley’s wife and son who were allowed to take a car from the crime scene and drive together for the interviews with the RCMP. Although the reports vindicate Baptiste, they do little to vindicate the Indigenous people who were in the car with Boushie including two Indigenous women who saw him die. All of the Indigenous witnesses were also in my view treated poorly in the court process. The RCMP is part of a larger criminal justice system that does not generally treat Indigenous people as well as white people.

• Better policing with Indigenous co-operation

The commission’s report cites a case where the RCMP worked with a Saskatchewan First Nation to prepare a sensitive press release that recognized an Indigenous woman had been killed and that she was a mom, a sister and a daughter, and that some in the community might not trust the RCMP. (This was in stark contrast to the first press releases in the Boushie/Stanley case, which focused on allegations of property crime against the Stanleys and did not mention that Gerald Stanley had been charged with murder). Help from the community was forthcoming and an arrest made hours later after this much more respectful approach.

This type of co-operation requires the RCMP to build trust with specific Indigenous communities, something that is difficult to do given frequent transfers of RCMP personnel in and out of the community. The commission did not recommend strategies to alleviate longstanding Indigenous distrust of the RCMP. It did not recommend strategies to do more than teach RCMP “cultural humility” but to actually ask for Indigenous communities to “aid and assist the officers of Her Majesty” as contemplated in Treaty 6.

• Cultural sensitivity versus police culture and

The commission’s recommendations that the RCMP employ mandatory cultural sensitivity training begs the question of whether such training can make a dent in RCMP culture. The RCMP already has 29 different courses on Indigenous issues. The RCMP in Saskatchewan announced that all of its members would have “successfully completed the Cultural Awareness and Humility course” by April 1. Nevertheless, there appears to be no process to measure whether this education will change RCMP conduct.

The Ontario Provincial Police has a more intense approach to training which requires officers to spend five days on the land with Indigenous people. That is something that can make willing students learn a bit about Indigenous laws, but this begs the case whether all RCMP officers will be willing students.

Both the response from the RCMP’s F Division in Regina and the commissioner’s own responses to the reports do not particularly demonstrate cultural humility. They both stress the belief that commission’s conclusions the RCMP’s investigations were done in a professional manner and that all its members acted “with the best of intentions; their priority was to ensure public safety and to complete a thorough homicide investigation and lay charges in relation to Colten Boushie’s death.” Education for the police is not enough. It needs to be supplemented by regular and meaningful meetings with Indigenous communities and a willingness to share responsibility for community safety (as well as necessary funding) with those communities.

• A slow and dysfunctional complaint and review process

Finally, the reports reveal how the civilian review and complaints system is slow and underpowered. The RCMP investigates complaints against itself. It rejected the family’s original complaint concluding that the aggressive approach and search of the Baptiste home was justified “for safety and tactical reasons.”

The RCMP seemed to accept the officer’s testimony that family members had consented to the search, even though the family denied it and the commission subsequently found there was no consent. The commission, which has an annual budget under $13 million, however, is in no position to investigate all complaints against the RCMP from coast to coast to coast.

The commission’s interim report on the Baptiste family complaint was given to the RCMP in November 2019. It then took 14 months for the RCMP commissioner to prepare her response. The RCMP conducted its own parallel review to the commission’s public interest inquiry for almost 18 months without informing the commission. The RCMP also destroyed radio communication, following its two-year retention policy, even though it knew the complaints and reviews were pending. The RCMP has promised to examine this matter, but again this underlines the necessity for independent civilian review as well as more robust ministerial oversight.

Proposed new legislation to give the commission new responsibilities over the Canadian Border Service Agency has not been re-introduced since Parliament was prorogued. When it is eventually re-introduced, the new bill will require drastic enhancements to give the commission new powers and resources – for example, remedial powers it does not have. The minister of Public Safety also needs to use his powers to issue ministerial directives to the RCMP and to make them public.

The RCMP needs to reject its para-military origins and become a truly civilian agency. It needs to embrace broader approaches to community safety and accept much more robust civilian governance and review.

The RCMP also needs to respect the expertise of Indigenous communities that know what is best for their own people and have their own ways of maintaining peace. No amount of cultural awareness training will change the deep structural and cultural problems in the RCMP.

For the purposes of this article, the author discloses that he provided training to the Civilian Review and Complaints commission for the RCMP on systemic discrimination against Indigenous people in the criminal justice system.