As a new Secretary of State for External Affairs, it seemed to me that I ought to establish a foreign policy with the twin objectives that Canada should receive maximum advantage from its foreign relations and that it should play a fully responsible role in the international scene. I was convinced that this required both broad public support for foreign and aid policies and an ability, on my part, to weigh independently the advice I received from public servants.

It is natural that advice from public servants would be based on a continuation of existing policy — policy which, in large part, had had its genesis within the department. And while it was not necessarily wrong, neither was it necessarily right. A new minister must be able to assess, for himself or herself, where we have been and where we ought to be going.

This did not mean a wholesale rejection of everything that had gone before or was currently in process; but, given my desire to develop a foreign policy attuned to the turbulent 1980s, I was determined that advice as to how we could achieve that goal should come from more than one quarter. It was, and is, natural that senior bureaucrats would have their own methods of gaining approval for the decisions they both needed and especially wanted. A new minister, just trying to find his or her way through the labyrinth of bureaucracy, is indeed vulnerable to such practices. A new minister in a new government which had not paced the corridors of power for some sixteen years is not only vulnerable but, indeed, almost without protection.

To reduce this dependency on bureaucratic advice and to provide a mechanism that would ensure political input into the decision-making process, a cabinet committee system was devised by the prime minister which aimed to establish a better equilibrium between ministers and mandarins. While this mechanism was being set up at the cabinet level, I personally moved on two fronts to ensure that I was the recipient of independent advice I considered would be critical to my own survival as an effective minister.

First, I determined that my personal staff would play a critical role in the evaluation of all sensitive policy issues. Although few in number, their independent and sometimes irreverent analysis of these issues was invaluable.

Secondly, with the co-operation of some interested persons from outside government circles — experts, primarily but not exclusively from the ranks of academe — I had taken the initial steps in developing what I hoped would be a mildly formalized structure to offer ongoing advice.

Without some such protective mechanisms, the minister is indeed at the mercy of bureaucratic domination, not because of some devious manipulative plot, but simply because that is the way the system has been allowed to develop.

Without some such protective mechanisms, the minister is indeed at the mercy of bureaucratic domination, not because of some devious manipulative plot, but simply because that is the way the system has been allowed to develop. To emphasize the point, and the concerns that flow from it, and because others have documented it so much better than I, I will refer to the memoirs and speeches of several cabinet members who faced a similar situation.

Anthony Wedgewood Benn began a recent lecture, entitled “Manifestos and Mandarins,” with the statement: “There are conflicts and tensions within our political system which receive a great deal of public attention. One relationship which has received far less public attention than its importance justifies is the balance of power between Ministers and senior permanent government officials.

He continued: “It would be a mistake to suppose that the senior ranks of the civil service are active Conservatives (or in Canada, Liberals) posing as impartial administrators. The issue is not their personal political views, nor their preferences for any particular government. The problem arises from the fact that the civil service sees itself as being above the party battle, with a political position of its own to defend.

“Civil service policy — and there is no other way to describe it — is an amalgam of views that have been developed over a long period of time. It draws some of its force from a deep commitment to the benefits of continuity, and a fear that adversary politics may lead to sharp reversals by incoming governments of policies devised by their predecessors, which the civil service played a great part in developing.”

In a country like Canada with a long history of one party dominance, this tendency is even more entrenched. Benn goes on to list the techniques employed by the doyens of Whitehall when ministerial views differ from their own:

“By briefing Ministers — the document prepared by officials for presentation to incoming ministers after a general election comes in two versions, one for each major party.

“It is a very important document that has attracted no public interest, and is presented to a Minister at the busiest moment of his life — when he enters his department and is at once bombarded by decisions to be made, the significance of which he cannot at that moment appreciate.

“The brief may thus be rapidly scanned and put aside for a proper reading when the pressure eases, which it rarely does.”

“Thus Ministers are continually guided to reach their decisions within that framework. Those Ministers who seek to open up options beyond framework are usually unable to get their proposals seriously considered.”

“By the control of information — the flow of necessary information to a Minister on a certain subject can be made selective, in other ways restricted, delayed until it is too late, or stopped altogether.

“By the mobilisation of Whitehall — it also easy for the Civil Service to stop a Minister by mobilising a whole range of internal forces against his policy.

“The normal method is for officials to telephone their colleagues in other departments to report what a Minister if proposing to do; thus stimulating a flow of letters from other Ministers (drafted for them by their officials) asking to be consulted, calling for inter-departmental committees to be set up, all in the hope that an unwelcome initiative can be nipped in the bud.”

Tony Benn’s lecture dealt with the interface between cabinet ministers generally and their senior mandarins. Henry Kissinger in his recent book The White House Years deals with the particular problems which confront a Secretary of State:

“Cabinet members are soon overwhelmed by the insistent demands of funding their departments. On the whole, a period in high office consumes intellectual capital; it does not create it. Most high officials leave office with the perceptions and insights with which they entered; they learn how to make decisions but not what decisions to make. And the less they know at the outset, the more dependent they are on the only source of available knowledge; the permanent officials. Unsure of their own judgement, unaware of alternatives, they have little choice except to follow the advice of the experts.

“This is a particular problem for a Secretary of State. He is at the head of an organization staffed by probably the ablest and most professional group of men and women in the public service. They are intelligent, competent, loyal and hardworking. But the reverse side of their dedication is the conviction that a lifetime of service and study has given them insights that transcend the untrained and shallow-rooted views of political appointees.

“When there is strong leadership, their professionalism makes the foreign service an invaluable and indispensable tool of policymaking. In such circumstances the foreign service becomes a disciplined and finely honed instruments; their occasional acts of self-will generate an important, sometimes an exciting dialogue. But when there is not a strong hand at the helm, clannishness tends to overcome discipline. Desk officers become advocates for the countries they deal with and not spokesmen of national policy; assistant secretaries push almost exclusively the concerns of their areas. Officers will fight for parochial interests with tenacity and a bureaucratic skill sharpened by decades of struggling for survival. They will carry out clear-cut instructions with great loyalty, but the typical foreign service officer is not easily persuaded that an instruction with which he disagrees is really clear-cut.”

Finally Richard Crossman, in his very revealing diaries, has this to say:

“Now for my impressions of the ministry and of the civil service. The main conviction I had when I got there was that the civil service would be profoundly resistant to outside pressure. Was that true? I think it was. I found throughout an intense dislike of bringing people in, whether they are politicians or experts.”

“I should say that in general I have found profound resistance in the civil service to a Minister who brings in outside advisers and experts, and profound resistance to interference by anybody with direct access to the Minister. What they like is sole ministerial responsibility because they are convinced that under this system the amount of outside influence exerted is minimal.”

Am I exaggerating when I use these British and American examples of resistance to ministerial attentiveness to outside advice and apply them here in Canada? I do not think so. But I think that that resistance resides almost entirely among those who really have their hands on the levers of power — the senior mandarins. And I sometimes felt they reacted as negatively to the creativity and imaginative proposals of those in the less senior ranks of the foreign service as they did to outside advice. One of my constant frustrations was to find ways in which to penetrate senior management levels so as to tap this well-spring of fresh ideas, creativity and provocative questioning which I know from some experience exists.

One of my constant frustrations was to find ways in which to penetrate senior management levels so as to tap this well-spring of fresh ideas, creativity and provocative questioning which I know from some experience exists.

I found myself as vulnerable as any new minister in any new government to the techniques Tony Benn attributes to the mandarins in Whitehall. He refers to them as techniques; I often thought of them as entrapment devices. Let me give you some examples:

The unnecessarily numerous crisis corridor decisions I was confronted with — here is the situation: (breathless pause), “Let us have your instructions.”

- The unnecessarily long and numerous memos; one of my great triumphs was that, in the wake of an abject plea for mercy, the senior re-write personnel agreed to reduce their verbiage by half.

- The late delivery to me of my submissions to cabinet, sometimes just a couple of hours (or less) before the meeting took place, thus denying me the opportunity for a full and realistic appraisal of the presentation I was supposed to be making to my cabinet colleagues. On a number of occasions my aides resorted to obtaining bootleg copies of such documents on their way through the overly complex bureaucratic approval system.

- The one-dimensional opinions put forward in memos. I was expected to accept the unanimous recommendation of the department, though of course there was always the possibility that I might reject it. Seldom, if ever, was I given the luxury of multiple-choice options on matters of major import.

I mentioned earlier that in order to ensure political input into the decision-making process, the cabinet committee system grouped together ministers whose responsibilities were inter-related. Thus, all those ministers whose duties took them into the international field were members of the cabinet committee on foreign and defence policy, the one body where their initiatives could be co-ordinated. I was mandated by the Prime Minister to be chairman of that committee.

As such, I had to be rigorously scrupulous not to allow my departmental interests to prejudice my impartiality as chairman of the committee. The system was designed to provide an independent source of information to ministers, and particularly to cabinet committee chairmen, through the cabinet secretariat of the Privy Council Office. Memos for the chairmen, drafted by secretariat officials, analyzed the issues on the committee’s agenda and pointed out the strengths and weaknesses of the various departmental positions. Deputy ministers or other officials participated in such cabinet committee meetings only if the agenda item required their attendance.

There was no comparable committee at the deputy minister level. In my view that would have undermined the decision-making role of ministers.

Not that such a committee of deputy ministers wasn’t suggested. It was urged on me in a succession of proposals which I consistently rejected. Such a committee headed by a deputy whose mandate was solely that of chief officer in the department of External Affairs would, I felt, hardly by acceptable to National Defence, Industry, Trade and Commerce, Immigration, etc., as the person to co-ordinate their policies at the bureaucratic level. In addition, such a committee of deputy ministers would usurp or at least conflict with the function of the cabinet secretariat in the PCO. One senior mandarin used these words to describe it when he first heard of the proposal: “A mechanism to facilitate conflict.”

I thought it was a dead duck; now I hear it has been activated and given the impressive title of Mirror Committee of Deputies. One wonders how many such mirror committees or deputies a cabinet minister can cope with before he or she ends up surrounded by a wall of mirrors each one reflecting the wisdom of the other into infinity. Even Alice in Wonderland might have difficulty in finding her way through what is likely to become a looking glass jungle, presenting the illusion of ministerial control.

Not only did I discover, after the takeover of the current administration, that senior mandarins had been successful in establishing this committee whose very operation must conflict with that of the cabinet secretariat, but I have also been led to believe that during my tenure copies of the private and confidential analysis done for me as a cabinet committee chairman by the PCO cabinet secretariat found their way to my deputy’s desk, without my knowledge or indeed without the knowledge of those who drafted the memoranda.

This would have permitted one senior official to be in a position to have access to privileged information not available to other deputy ministers, nor indeed to cabinet ministers other than the committee chairman. One need hardly speculate on the important role control of information plays in the bureaucratic game.

On a more philosophical level, I am concerned that the proliferation of senior management co-ordinating committees — co-ordinating advice not only to senior ministers but now to groups of ministers — will seriously impair the decision-making role of ministers. Such a system effectively filters out the policy options that an entire committee might otherwise consider. Too many bureaucrats, I fear, have the mistaken impression that vigorous debate of policy options by cabinet ministers is an indication that they — the bureaucrats — have somehow failed to properly channel and co-ordinate views before the cabinet meeting takes place.

Regrettably too few Canadian ministers have followed the example of Richard Crossman, Tony Benn, Harold MacMillan, Henry Kissinger or Dean Acheson in providing a first hand account of the relationship between the minister and the bureaucracy. Regrettably as well, academics in this country have not paid as much attention as they should to the interface between ministers and the senior echelons of their departments.

The effective management of that relationship is what distinguished parliamentary government from bureaucratic management. As Anthony Wedgewood Benn concluded: “In considering these issues, we do not want to find new scapegoats or pile blame upon ministers or civil servants who have let the system grow into what it is. What matters now is that we should examine what has happened to our system of government with fresh eyes and resolve the reintroduce constitutional democracy to Britain,” and, I might add, to Canada.

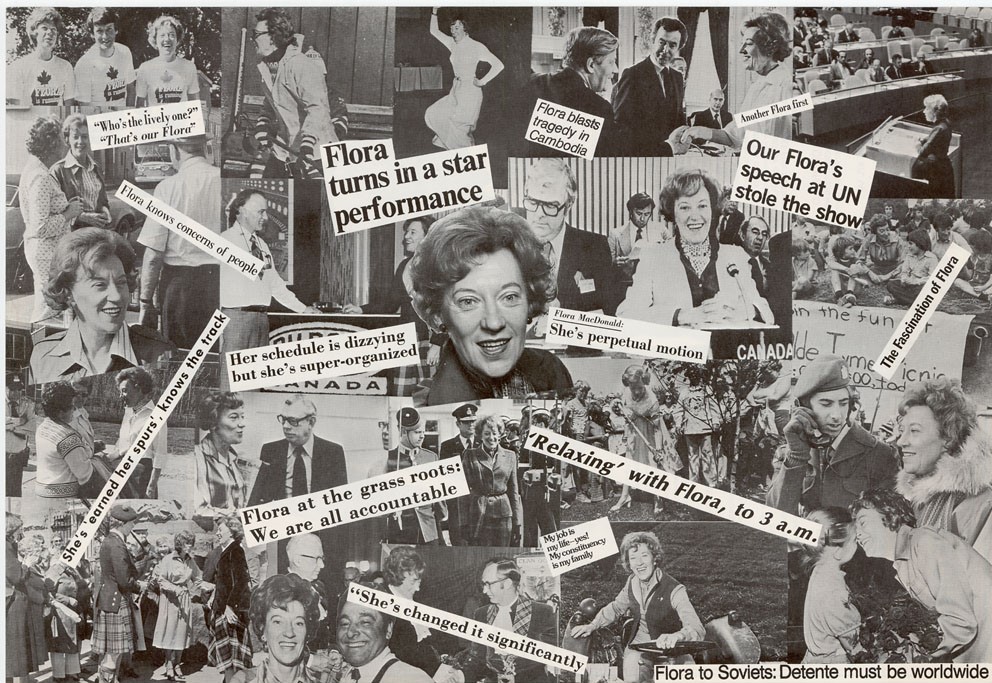

Photo: Flora MacDonald speaks to mayor Mel Lastman, centre, of North York, January 7, 1980 during a campaign swing through the region. At left is Progressive Conservative candidate Bob Jarvis. In centre is David Rotenberg. Photo by John McNeill / The Globe and Mail.