Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne admitted late last year that the provincial government had “made a mistake” and mismanaged electricity prices in Ontario. In doing so, the Premier was acknowledging what many experts had been saying for some time. As Ontario’s Auditor General wrote about Ontario’s electricity system in 2015, “the planning process had … broken down over the past decade,” and the government made decisions that resulted in “significant costs to electricity consumers.” The Government of Ontario announced finally in March 2017 that it will cut electricity rates by an average of 17 percent starting this summer. It will do so primarily by refinancing “global adjustment” payments – effectively repaying electricity contracts over 30 years instead of 20 years.

While the move will save customers money before the next provincial election in 2018, it will do so only by adding another $25 billion in long-term interest payments. Also, the electricity system of tomorrow will face increased costs from nuclear refurbishment, aging asset replacement, climate adaptation, carbon pricing, and expansion of electrification into other sectors. These costs will add up. Given the range of challenges ahead, it is imperative that Ontario pursue cost savings and policy improvements. Here are seven ideas that merit greater discussion.

Increase transparency in electricity pricing

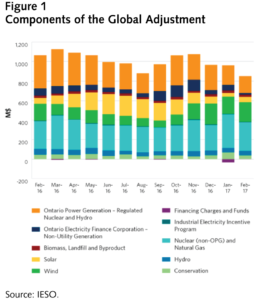

The Ontario Energy Board (OEB) has stated that it wants to build “trust” and “energy literacy” among customers — two worthy objectives. Yet it has opposed proposals that would give customers better cost information. It has opposed one request to show carbon cap-and-trade costs as a separate line item on electricity bills, and a second one to show the breakdown between the market-clearing price for electricity and global adjustment (GA) costs (the market-clearing cost being the price where supply of a service and demand for it are equal). The market-clearing price for electricity only reflects the short term operating and fuel costs of the most expensive generator at a given moment. But generators have other costs too. In Ontario, when generators are paid regulated prices or contract prices that are higher than market-clearing prices, the difference is made up by the global adjustment charge, an umbrella charge added to electricity bills (See Figure 1). The GA also includes other expenses such as conservation programs.

The global adjustment is complicated, so it is understandable that few customers understand it. But its opacity has made it easier for various costs to accumulate with very limited public review. Electricity bills should show how much customers pay for their energy usage, plus how much of their bill is related to the global adjustment costs. Doing so would encourage greater scrutiny of all the costs that get bundled into the GA and justifications for those costs. In addition, the OEB could publish a monthly table comparing the GA costs of each type of energy with its proportion of energy production, so that customers can get a sense of the relative cost per kWh of the different sources of energy. In the case of conservation programs, their costs could be compared with their reductions in consumed energy.

Pursue “biggest bang for buck” carbon reductions

Ontario points out that the coal shutdown is the “single largest climate change initiative undertaken in North America.” Unfortunately, the way it was implemented was very expensive, with an average (implied) cost of $100 to $130 per tonne of carbon reduced. And the cost per tonne of carbon reduced by renewable energy projects initiated under the Green Energy Act (wind, solar, hydro and biomass) ran even higher: for instance, above $1,000 per tonne in 2013. That implied carbon cost was not arrived at because all other cheaper carbon reduction measures had been exhausted. Rather, that was just how the math worked out in an over-supplied electricity system with very little carbon-emitting generation actually displaced by the subsidized renewables.

Current policy is a patchwork of carbon prices. The cap-and-trade regime, soon to be tied to Quebec and California’s market, has a price of about $18/tonne. The province’s Climate Change Action Plan outlines an initial set of mitigation measures, some aiming to reduce emissions in 2020, and others only later. It indicates a wide range of costs for these measures — from $5/tonne to $525/tonne — but does not explain the assumptions underlying these costs. Crucially, there is no base case for each initiative against which incremental emissions changes and the costs of those changes can be analyzed, and no evidence the government will prioritize cheaper reductions over costlier ones. Deep decarbonization studies show that achieving the stated 2030 and 2050 targets will not be easy or cheap. Precisely for that reason, emissions reductions should be as efficient as possible.

Align energy and carbon planning

Some of Ontario’s recent policy decisions intended to benefit the environment have become a cautionary tale: neither the environment nor the economy is served by aggressive environmental policies that prove to be economically unsustainable. The energy transition requires good planning and sustained momentum.

But the province has yet to revise its policies to reflect this lesson. For instance, it has not repealed the Green Energy Act which set overly expensive rates and led to overly generous long-term electricity contracts. It has suspended, but not cancelled, the second round of its Large Renewable Energy Procurement (LRP II) process, despite forecasts showing that this additional electricity supply will not be needed. And as the Ontario Environmental Commissioner points out, the province has yet to issue a long-term energy plan to achieve its 2030 greenhouse gas emissions reduction target. Energy and carbon reduction plans must be carefully orchestrated.

Improve design and validation of conservation programs

Ontario allocates significant resources to conservation efforts. Utilities spent $421 million on electricity conservation programs in 2014, and the Independent Electricity System Operator (IESO) has earmarked an additional $2.2 billion for utilities to spend on conservation between 2015 and 2020.

Two important issues in the current conservation programs need to be addressed. First, the province should review how it validates energy savings from the programs. These programs, together with the codes and standards, are credited with saving about 67 TWh between 2005 and 2015.

Over the last six or so years, however, electricity price increases have far outpaced inflation. Basic economic theory suggests that such dramatic price increases will have their own impact on reducing electricity demand (see, for example, this report). But the terawatt hours reduced since 2010 are attributed solely to conservation efforts, and the effect of the price spike is not acknowledged. Even assuming minimal price elasticity of demand, the 67 TWh reduction credited to conservation is overstated.

The second issue is that to spend on conservation programs in a period of year-round over-supply does not make sense. Even as Ontario suppliers are selling surplus electricity to neighbouring jurisdictions at a deep discount, the government is subsidizing initiatives to reduce electricity consumption inside the province (through retrofits, light bulbs, etc.), thereby increasing the amount of surplus. Ontario is likely to remain over-supplied until about 2020. If the province cancelled planned spending on conservation between 2018 and 2020, it could save in the order of $1 billion (while continuing to improve codes and standards through relevant ministries). The hiatus would also give the province time to improve the design and validation of its conservation programs.

Develop robust capacity auction at earliest opportunity

All electricity systems need to ensure that they can call on adequate resources to meet fluctuating demand. Many electricity systems have both an energy market, in which generators are paid the market clearing price for their energy, and a capacity market, in which they are also paid for their ability to provide energy – in other words, they are also paid to keep “generation capacity available to produce electricity as required.”

Although capacity markets can be designed in different ways, in general they offer several potential advantages. They can help ensure reliability. They can also support cost-effective innovation and decarbonization by stimulating competition among would-be capacity providers. Capacity markets can also accommodate other types of contributions to grid cost-effectiveness and reliability – notably storage technologies, imports, and ‘demand response’ (incentives for customers to lower their electricity use during periods of peak demand).

Since much of Ontario’s supply is provided by regulated and contracted electricity generators, there is little scope to develop a full competitive capacity market. However, the IESO is working to develop an “incremental capacity auction” for Ontario to replace long-term contracts as they expire. A capacity auction would provide Ontario with greater cost transparency, as there would be a clear price signal for capacity costs (as opposed to the current situation in which these costs are bundled together with other costs in the GA). It also has potential to provide significant cost savings. The Brattle Group, a consultancy, just released a report for the IESO that reinforces the potential benefits of a capacity auction for the Ontario electricity market. The report projects $2.5 billion in benefits between 2021 and 2030 “from capacity auction reforms,” with benefits far outweighing implementation costs.

Yet there are challenges ahead. Given the government’s plan to amortize global adjustment costs over a longer term, customers will end up paying for some resources twice: one time through a new capacity auction, and a second time through deferred costs on the earlier contracts for those same resources.

Require consolidating utilities to show customer benefits

Since 2000, the number of distribution utilities in Ontario has dropped from about 300 to about 70. Consolidations should continue, and for three reasons. First, from a climate mitigation perspective, electrification of transport and space heating will require far more complex distribution systems — and therefore technology investments at scale to keep them affordable. Second, from a climate adaptation perspective, smaller utilities “may be more vulnerable to external events, such as storms which affect the distributor’s complete service area [and require] significant recovery efforts.”

Third, productivity gains and cost savings could be shared with ratepayers. Other jurisdictions have seen significant customer benefits: in Vermont for instance, the consolidation of two distributors in 2012 was expected “to save ratepayers US $144 million over 10 years, a 5.8 per cent reduction.” The OEB could require each applicant to demonstrate how its proposed consolidation is expected to generate any mitigation, adaptation and/or cost saving benefits for customers, and to apply for an update of its electricity rates within six years of the close of the transaction.

Establish public hearings for power system planning

The processes for obtaining public and expert input into electricity plans are marginal, at best. Several years ago the planning process included stakeholder input before the OEB, but only after the government had already provided directives that predetermined the plan’s key features. As the Auditor General put it, “In the absence of a technical plan, the Ministry [made] decisions about power generation that went against the [Ontario Power Authority’s] technical advice and did not fully consider the state of the electricity market or the long-term effects.”

More recently, responsibility for the Long Term Energy Plan was moved to the Ministry of Energy. While there are perfunctory stakeholder consultations, the government has eliminated the requirement that plans be subject to OEB review. In addition, energy agencies, instead of “providing checks and balances as they do in other jurisdictions,” will now need to show how well “they implement government directions.” The government should restore the OEB review process, and strengthen it by ensuring meaningful public participation, providing intervenor funding as in rate cases, and taking an evidence-based approach to decisions.

Conclusion

The province needs to build an electricity system that will be cost-effective, low carbon, reliable and resilient, and capable of electrifying other sectors. Sounds like a tall order? It is. If the government is serious in meeting all these objectives, it needs to learn from past mistakes and directly face the challenges and risks ahead. The year 2030 is right around the corner. Ontario needs to empower customers with information, relentlessly pursue efficiencies, provide clear market signals, and open up the planning process.

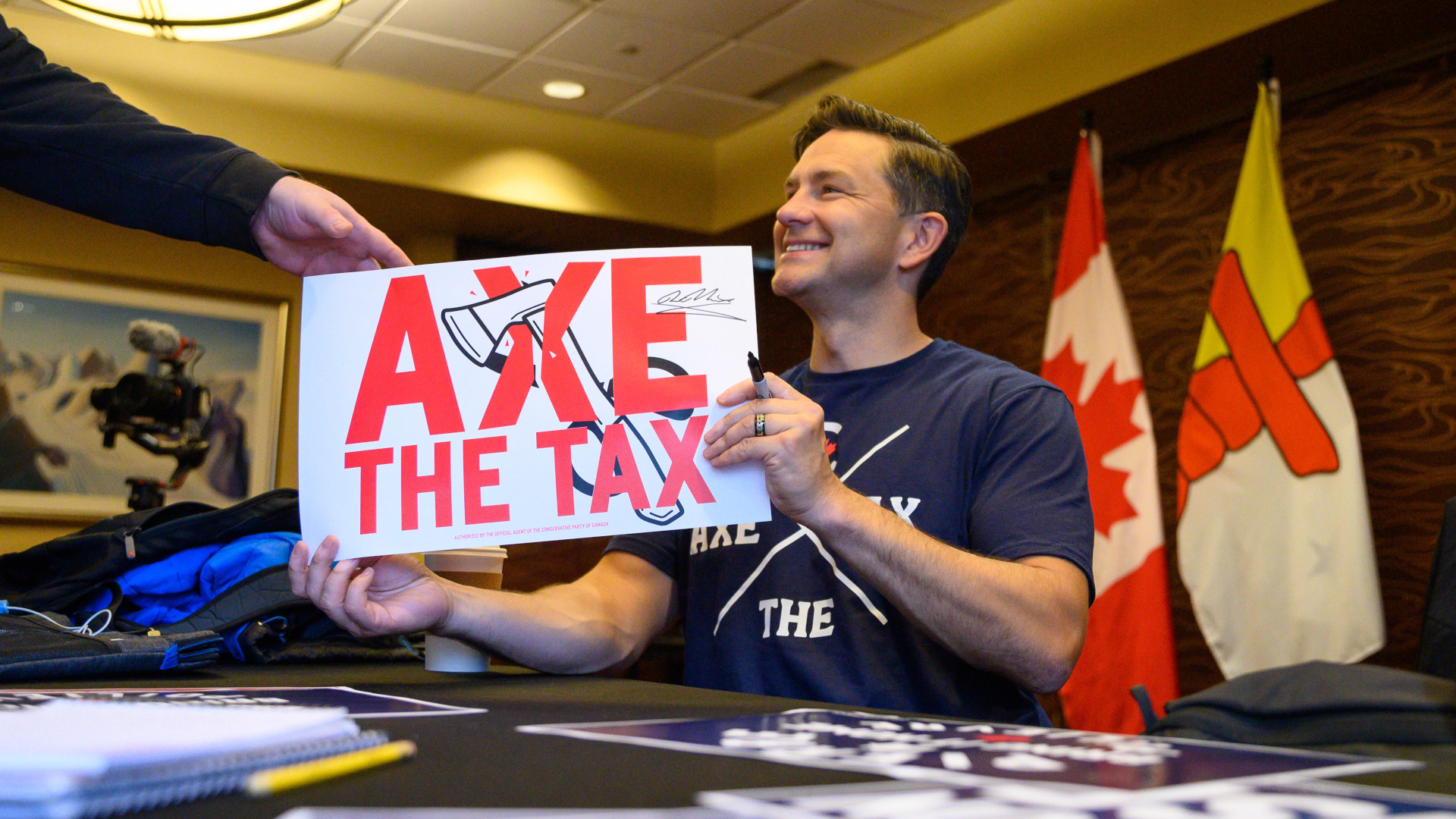

Photo: Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne speaks during a press conference in Toronto on Thursday, March 2, 2017. The Liberal government unveiled its plan today to cut hydro bills, which are the biggest political issue it faces less than a year-and-a-half away from an election. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Frank Gunn

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.