Democratic governments are supposed to express the people’s will and, for the most part, they do, if only out of self-interest. But there is one policy area where governments continually ignore the popular will and seek to impose “solutions” that the majority don’t want: urban transportation.

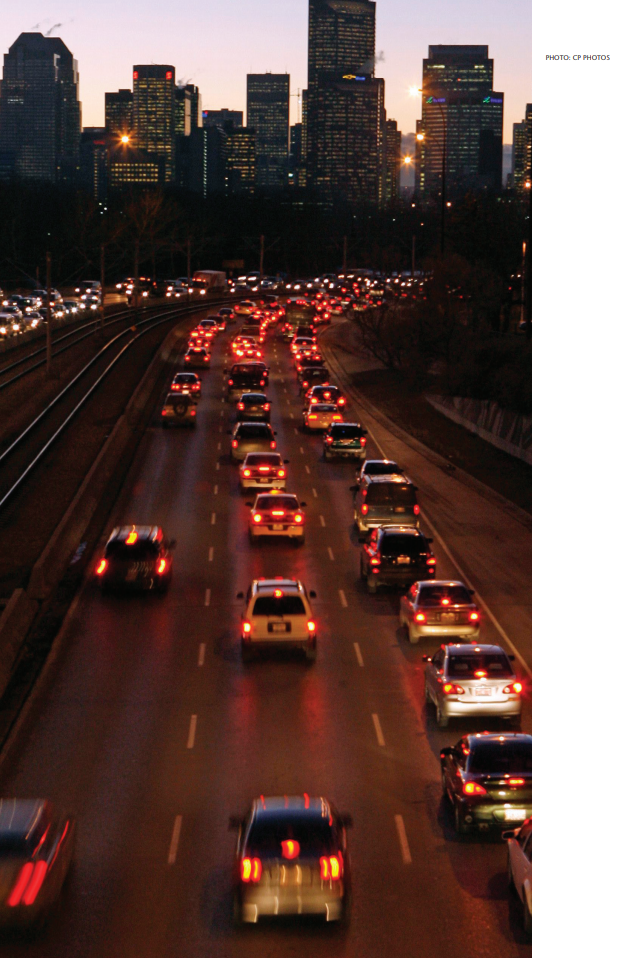

Evidence shows that Canadians overwhelmingly want to be able to drive through their cities on roads that are not potholed and at speeds not smothered to a near-halt by traffic congestion. Yet municipal governments across the country ignore this. Municipal governments are stuck on a preoccupation with developing and expanding expensive public transit systems in the absence of evidence that this is what their citizens want.

This is nothing less than an ideologically driven war on the car. And while that disconnect is evident in any medium to large city in Canada, it is felt deeply in Calgary, where the desire of drivers for a better-functioning road network is subsumed by visions of unfettered public transit. We know that because polling in Calgary is clear: the City of Calgary’s Citizen Satisfaction Survey conducted in 2012 placed mobility as the primary concern of Calgarians, with infrastructure, traffic and roads mentioned as the top priority by 29 percent of respondents and by 38 percent of respondents overall (public transit was mentioned first by 18 percent of respondents, and by a quarter in total).

Meanwhile Statistics Canada showed Calgary to be overwhelmingly a city of car drivers: 77 percent get to work by car compared with just 16 percent who go by public transit. The biggest issue for Calgarians, after concern about crime and other security matters, was traffic congestion and road infrastructure.

And yet the city’s official transportation policy goes in the opposite direction. Of the 26 principles, directions and goals in the Calgary Transportation Plan, only seven are primarily aimed at reducing the time and money costs of trips that Calgarians currently choose to make. Eight are devoted to offering greater “choice,” which turns out in many cases to be about promoting modes of transportation other than private cars.

There is no conflict between offering choice and improving mobility. Different modes of transport work better at different times. But mobility options should be chosen by those who need to be mobile. It is oxymoronic to foist something else on the public in the name of “choice.”

This is the division we face over transportation policy in Canada’s large cities. On one side is the all-knowing urban planning profession, betting against the public’s obvious preference to drive. On the other is a more organic urban form, with fewer arbitrary numerical targets and better pricing of transport services, embracing the idea that getting around farther and faster is not only good but inevitable.

The triumph of any city is that it brings more people into more-productive interactions than is possible in the countryside. Doing this requires mobility, and better mobility requires better technology. Even citizens in the densest cities, such as London, New York and Tokyo, use mechanized transport so that they can interact with more people in a given amount of time than they could by simply walking. This ability to visit widely and quickly with low time and money costs makes up much of the urban advantage.

Technology has always driven mobility. Shoes, horses, carts, trains, streetcars and the automobile have progressively increased human mobility at the same time as we have become immensely richer. The challenge of a good mobility policy, therefore, is to find ways to adopt technologies that can provide urban drivers with greater mobility at lower costs. (The Tom Tom Congestion Index ranks Calgary as the 26th most congested major North American city out of 59 studied, with Vancouver 2nd, Toronto 6th, Montreal 10th, Ottawa 18th and Edmonton 34th.)

But Calgary’s transportation policy assumes the day of the automobile is coming to an end just as the advent of new technologies is ushering in a new era of more efficient and less polluting car travel. Much current city policy operates on the basis that we have reached a high-water mark in this progression. The timing couldn’t be worse.

A host of technological and entrepreneurial developments promise to make road infrastructure more efficient, free up urban spaces, reduce transport emissions and energy consumption, save people time and improve safety, all while increasing mobility.

The urban planners’ infatuation with phasing out the car is out of step.

Self-driving cars: Once relegated to the sci-fi world or The Jetsons, self-driving cars promise to improve the use of existing infrastructure. Compared with cars driven by people, they are able to safely drive closer together and use less road space for a given traffic volume while reducing the likelihood of an accident. Nissan and GM have promised fully autonomous vehicles by the end of the decade, but it is already possible to purchase cars that manoeuvre themselves into parallel parking spaces or adjust their cruise control speed to maintain a safe following distance. Google has driven its prototype more than 500,000 kilometres without incident. Nevada has made it legal to operate autonomous vehicles on public roads, while California and Florida have made it legal to test them.

Ride sharing: The rise of GPS-equipped smartphones has helped make ride-sharing services possible. The Carma Carpooling app allows people to locate passengers and drivers making similar trips, with the potential to improve commuting efficiency by filling empty seats.

Car sharing: Car2Go, which allows people to access a car without owning it, is currently active in Calgary, Toronto and Vancouver. Aside from private benefits, this service has the potential to save urban space by reducing the proportion of the day that a vehicle is parked on city streets.

More-efficient propulsion: From 1949 to 2010, the fuel economy of light vehicles improved by 56 percent. There remains considerable potential to improve efficiency further with more-efficient propulsion, including electric vehicles. Some electric vehicles are achieving the equivalent of over 100 miles per gallon (2.35 L/100km).

Real-time road pricing: As technology lowers the price of tracking vehicles and transferring funds, charging car drivers for the precise time and place of road usage becomes viable. Such pricing could shut down the argument wielded by the promoters of public transit that drivers receive a subsidy in the form of tax-supported roads. -Real-time road pricing would lead to less guessing about consumer preferences and give us more accurate information about their behaviour. Road pricing in Stockholm has shown that congestion can be significantly reduced by pricing road use for different times of the day. Technology is bringing down the cost of operating such a system. And real-time road pricing would also be a fairer system because the users, rather than all taxpayers, would pay for them.

Intelligent transportation: Already in use by the City of Calgary, new systems can adjust traffic light sequencing, inform drivers of congestion and gather planning information by monitoring traffic flows in real time. There is great potential to further integrate these systems with other modes of transit, with road pricing and ultimately with autonomous vehicles.

Taken together, these features offer a future in which the current distinctions between public and private transport blurs. Vehicles might be owned by a company such as Car2Go, an international car-sharing service, offering lifts to other users travelling on a similar route and directed by intelligent traffic management systems in order to reduce congestion. They could self-park to reduce space consumption, and be charged a market clearing price for use of the roads at any given time, as well as be propelled by increasingly efficient power sources.

All these scenarios already exist in some form, either on the market, in use by city governments or at an advanced prototype stage. The question is whether technology can pacify the ideological zeal of the urban planning movement. At a recent Federation of Canadian Municipalities Sustainable Communities Conference, the planning crowd nodded wearily as the speaker lamented that electric cars might solve the emissions problem but also reduce the cost of driving.

We wouldn’t want to have that, would we?

Calgarians are repetitively subjected to the refrain that it’s just too costly to build out of the current over-congested model. They are told that even if more roads were built, they would be blanketed by extra cars just as soon as the last chip of bitumen was set in place.

The result is that much of Calgary’s mobility policy can best be described as an anti-mobility policy. Rather than accepting people’s choices of where to live and work and seeking to better connect the two, Calgary’s current transit plan sets goals for how people should travel. It seeks to mould decisions about where we choose to live around the kinds of transport that the City prefers to provide.

Several of the city’s initiatives are explicitly antimobility:

- Achieve greater use of more sustainable travel modes such as walking, cycling and public transit, while also reducing the average distance travelled by automobiles.

- These objectives will be achieved through ongoing operations, maintenance and public education programs, as well as mobility management and land use strategies that will reduce vehicular travel and improve public safety and health.

- These strategies will reduce demands on the transportation system by reducing vehicle trip distances and making public transit, walking and cycling more appealing mobility choices for more people.

The plan sets numerical targets for where Calgarians should live and how they should get around over the next 60 years: Housing density must increase to 27 residents with 18 jobs per hectare, up from the current 20 and 11, respectively. Half of all new development must be within the city’s 2005 urban footprint, even though the zone has traditionally been a net loser of population as residents spread outward. Auto use must fall from the current 77 percent to between 55 and 65 percent.

The City uses its fiscal power to push these trends. Spending on parking, roads and traffic was $355 million in 2012, less than the $438 million spent on public transit (remember, that’s much less than half the transport budget for the three-quarters of Calgarians who drive to work). Meanwhile, transit fares for the average trip rose 16 percent between 2007 and 2011, while public transit subsidies rose 82 percent.

Usually subsidizing a service leads to more people using it. But the higher subsidies for public transit have not altered the 77:16 ratio of car drivers to transit riders. It was the same in 2006 as it was in 2011. The reason may be because, according to the Statistics Canada household survey, transit commute times in Calgary remain significantly longer (32.3 minutes on average from home to work) than by car (23.7 minutes), even with Calgary’s infamous road congestion.

Cities are not static. The transportation networks and the way we use them are constantly changing. One consequence is that we may be using out-of-date assumptions to make transport policy. Mobility has always been measured on the basis of our routine, point-to-point trips. But as Australian geographer Clive Forster has recently written: “Current metropolitan planning strategies suggest an inflexible, over-neat vision for the future that is at odds with the picture of increasing geographical complexity that emerges from recent research on the changing internal structure of our major cities.”

Modern life involves much more complex trips for children’s activities, suburban workplaces and suburban shopping centres than the old in-and-out central city paradigm suggests. An alternative scenario for our cities is that private vehicle travel is at the beginning of a new golden age, fuelled by more powerful computer processors, sensors and electronic communications. Vehicles may become more likely to be shared among multiple users, to drive themselves and to intelligently coordinate with each other to reduce congestion. They should be able to respond to market pricing to ensure more-efficient use of infrastructure, and use more-efficient methods of propulsion to reduce energy and emissions concerns.

All these suggest that the infatuation of urban planners with phasing out the car is out of step. By aiming to increase density and reduce vehicle-miles travelled, the City’s goals are the opposite of increased mobility and less congestion. It’s time to abandon this agenda that favours one mode over others and explore the possibilities offered by technology to get people where they want to go faster and at lower cost. That means listening to the people, many of whom prefer to drive and who want to do so with a lot less aggravation.

The paper on which this article is based, and other Manning municipal papers, can be found at www.manningfoundation.org/our-work.

Photo: Shutterstock by Sofiaworld