When Manitoba’s rookie premier Greg hosts the annual meeting of the Council of the Federation this summer, he may be in for a bit of a surprise. The friendly and productive sessions of the past few years are likely to be replaced by some serious outbreaks of acrimony.

The council was created in December 2003 to provide an ongoing structure and focus for the annual meeting of provincial and territorial leaders, who agreed to “promote interprovincial-territorial cooperation and closer ties between members…, foster meaningful relations between governments based on respect for the Constitution and recognition of the diversity within the federation, and show leadership on issues important to all Canadians.”

Council meetings have been pretty tame affairs in the past few years, and for several good reasons:

- The Martin government’s 2004 10-year deal with the provinces and territories on health care financing established steady and predictable increases in federal transfers, essentially taking that contentious issue off the table for a decade.

- Stephen Harper’s 2007 budget took a number of steps to address the fiscal imbalance within the federation, increasing transfers by a total of $39 billion in additional funding over seven years for equalization, the Canada Social Transfer, labour market training, infrastructure, and Canada ecoTrust for clean air and climate change.

- There’s been progress on interprovincial trade. Premiers Selinger have finally reached the conclusion that since free trade is working so well for Canada internationally, it might actually be worth a try within our borders! In 2007, Alberta and British Columbia reached their Trade, Investment and Labour Mobility Agreement to ease access to each others’ internal markets, and other provinces have been looking at similar arrangements. In 2009, the council made additional progress in addressing internal trade barriers, outlawing technical measures to diminish trade in agricultural products and enhancing labour mobility between provinces.

- In February 2010, the premiers held an apparently successful round of meetings in Washington with the National Governors’Association to focus on common border issues, energy and the environment.

So what’s changed? And why might Premier Selinger face some rather surly guests when he hosts his August meeting? The answer is because of three separate issues: health care financing, the environment and equalization. The health care issue is pretty straightforward, and features the classic federal-provincial challenge of trying to match fiscal resources with program responsibilities. That one won’t drive the premiers apart, but the other two issues likely will be a lot more explosive. They have the potential of pitting province against province, with the federal government potentially cast in the role of peacemaker. And some of the unfortunate linkages that are developing between the environment and equalization mean that making peace will be a tall order.

The coming battle over health care financing is a movie we have all seen before, but not for a while. The reason is that Paul Martin’s 2004 Canada Health Transfer deal bought a decade of peace with the provinces over the funding of this country’s signature public program. The operative word here is “bought,” because the agreement reached in 2004 actually set the cash levels to be transferred in legislation through an automatic escalator that established a growth rate of 6 percent annually over the life of the agreement. That formula will provide $25.4 billion to the provinces in the current fiscal year, rising to over $30 billion in 2013/14. In addition, there’s a tax transfer for health care that grows in line with the economy, which this year will provide an additional $13.1 billion to support provincial health care programs.

When Paul Martin opened the September meeting with the premiers that led to the 2004 deal, he placed a number of issues on the table, notably the need to reduce wait times for diagnostic procedures and treatments, family and community care reform, better planning for health human resources, greater access to home care, and improved Aboriginal health. Clearly some progress has been made. As the Canadian Institute for Health Information reported at the end of 2009, strategies to reduce wait times have demonstrably improved access in a number of areas. Innovations in surgical techniques are leading to less invasive surgery, and new therapies for a number of conditions can now be tailored to patients’ genetic characteristics. Heart and stroke care is more effective, and survival rates are going up.

Another key area of health care reform has not proven to be nearly as successful. For years, the federal and provincial governments have poured billions of dollars into health information infrastructure with the objective of reducing paper, creating electronic health records, enabling more real-time analyses and developing templates that make information available in various formats. These efforts have had disappointing results, and in Ontario and BC they have been accompanied by damaging spending and contracting scandals that have set back the process and threatened public support. Economists have been warning for years that health care expenditures growing at a minimum of 6 percent per year are unsustainable in the long-term, and that’s why the failure of the health infrastructure investments to produce efficiencies is so disappointing.

The 2004 Martin health care deal and the tremendous growth in federal transfers it has fuelled were both made possible by the expansion of the national economy, which continued throughout most of the first decade of the 21st century until the fall of 2008. At that point the international recession hit with a vengeance, and the federal and provincial governments suddenly found themselves in deficits due to plunging revenues and the rising stimulus spending needed to support their economies.

There’s been progress on interprovincial trade. Premiers have finally reached the conclusion that since free trade is working so well for Canada internationally, it might actually be worth a try within our borders!

While Canada is clearly moving out of the recession, even if the March 4 budget’s forecasts are borne out, there will still be a federal deficit of $8.5 billion in 2013/14, when the next health care agreement must be negotiated. That’s not necessarily a dealbreaker from the federal point of view — we are, after all, talking about the singular program that has come to define Canadian citizenship — but it’s likely to be a practical constraint. Equally so will be the provincial debt situation in 2013/14. With total provincial deficits that CIBC recently estimated to be in the $70 billion range, the federal government will be watching provinces closely over the next two to three years to see if they are managing down their deficits.

The real wild card in the next federal-provincial health care negotiations, and the one likely to strike the most fear in the hearts of provincial finance ministers, is the looming demographic challenge. The Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) recently documented the coming rise in the share of Canada’s population that is 65 years of age and older, beginning in the next couple of years as the younger members of the baby boom generation begin to reach retirement. Given that maximum demand on the health care system rises with age, the real crunch from this demographic juggernaut is still some years away, but it is inevitably coming. Equally important is this projection from the PBO:

the old age dependency ratio, defined as individuals 65 years of age and over divided by the population between 15 and 64 years of age, is projected to increase significantly in the coming decade rising to 26.7 percent by 2019, a 7-percentage point increase, which is roughly equivalent to the total increase observed over the

last four decades.

In other words, we are facing a future with not only a rising proportion of elderly Canadians making greater demands on health care, but also a decline in the population of working age Canadians who will be called on to meet those rising costs. That’s not a scenario designed to bring a smile to any finance minister’s face, federal or provincial.

What are the preconditions for a successful health care deal in 2013-14? First, that the economic recovery now underway continues and matures into steadily growing government revenues.

Second, that the federal and provincial governments get their current deficits under control, and get firmly on a track toward budget balance. Those are fairly significant “ifs,” but they are just the starting point. Given the demographic realities facing them, the provinces and territories will likely see renewal at a 6 percent growth rate as a starting point for the negotiations. But a federal government that since 2007 has been in the process of transferring $39 billion to the provinces to address the fiscal imbalance may see that growth rate as the best it can do. Either way, there remain some serious questions on the fiscal sustainability of health care spending to be resolved in the long run.

Let’s leave the last word on this question to the Minister of Finance. In his postbudget interview with Policy Options in April 2010, Jim Flaherty addressed the growth of health care expenditures at the provincial level:

I tried to deal with it in Ontario when I was finance minister there, and it’s a tremendous challenge, because regardless of the degree of economic growth, health care costs will march along growing at 6 percent, 7 percent, 8 percent, 9 percent per year in the absence of any rational containment of health care costs, and it would be not good for the federation, for the provinces to just try to dump excess health care costs on the federal government, because the federal government doesn’t have the tools to control health care costs because it’s not our direct jurisdiction.

The second growing flashpoint in federal-provincial relations is the environment.

The Harper government came to office unsure of its position on global warming and unclear on how to proceed. Their first discovery was that they had been left an empty vessel by the Liberals. Despite brave promises to meet the Kyoto targets, there was no real plan for how to achieve those objectives. The necessary industry-by-industry negotiations had not taken place, and there was no agreement on the market mechanisms essential for managing down GHG emissions. There were other complex questions to resolve: should targets be “intensity-based” or “true reductions,” and would the reference year be Kyoto’s or a more recent date?

In 2007, the federal government formally abandoned the Kyoto target of a 6 percent reduction from 1990 levels by 2012, and established new targets for a reduction of 20 percent below 2006 levels by 2020 and 60 percent by 2050. It then set to work to develop the market mechanisms and the sector-by-sector negotiations necessary to set regulations. Meanwhile, with their economies booming and public opinion calling for action, several US states and Canadian provinces became restive at the apparent lack of action on climate change by their respective federal governments, and decided to move on their own:

- First up in 2007 was the Western Climate Initiative, involving several western US states and the provinces of British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario and Quebec, which collectively committed to work toward a functioning capand-trade system by 2012.

- In 2007, Ontario announced a 6 percent reduction target (based on 1990 levels) by 2014, a 15 percent reduction by 2020, and 80 percent by 2050, and British Columbia set its targets at 33 percent below 2007 by 2020 and an 80 percent reduction by 2050.

- In 2008, Alberta established the long-term goal of stabilizing emissions and beginning reductions by 2020, and then reducing emissions by 14 percent below 2005 levels by 2050.

- In late 2009, Quebec adopted the European Union standard of a 20 percent reduction from 1990 emissions levels, the original Kyoto target.

As it turns out, most of these targets were little more than public posturing — attempts by the various governments to convince their electorates that they were “really really” serious about taking action on climate change. Real and measurable results have been few and far between. And given its popular reputation as the “bad boy” of GHG emitters, it’s more than a little ironic that Alberta is the only administration in North America to have put in place a regime with real requirements for reductions (albeit intensity-based) and workable market mechanisms to achieve them. A year ago, Alberta was able to report that it had reduced GHG emissions by 6.5 million tonnes in the first 18 months of its program, and that Alberta emitters had paid $122.4 million into the province’s Climate Change and Emissions Management Fund, which supports innovative emissions reduction technologies.

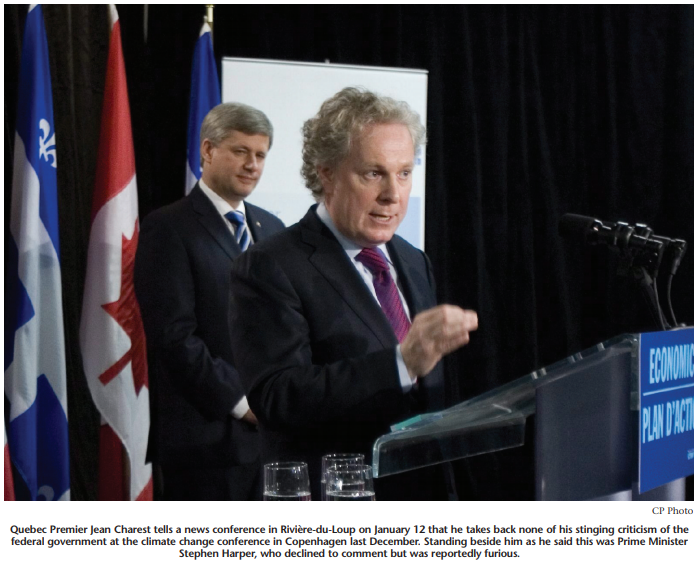

Imagine Alberta’s surprise, then, as it found itself the subject of drive-by attacks over the oil sands during the last six months from Quebec and Ontario. First, Premiers Jean Charest and Dalton McGuinty met last September to warn that they would not stand for the federal government capping manufacturing emissions in their provinces in order to allow lower emissions reduction targets for Alberta’s oil sands. Then in Copenhagen in December, the environment ministers from Quebec and Ontario repeated their criticism, warning they would not shoulder the burden of GHG emissions reductions on behalf of the oil sands. While their ostensible target was the federal government, the overall message was not lost on Alberta. Alberta responded with ads in major Canadian newspapers with a not-so-subtle reminder for Quebec and Ontario of the economic benefits they realize from oil sands development: “No one should ignore the economic stakes of this debate. Slowing our economy is a guaranteed way to reduce emissions. But if Alberta’s economy stops growing, all Canadians will feel this pain.”

The pièce de résistance for Alberta came in February, when the Quebec Department of Economic Development’s Web site urged Quebec businesses to get in on the coming bonanza in the oil sands. The Web site explained that Suncor, Encana and Imperial or were going to be spending $200 billion on oil sands development in the coming years, and invited businesses to join a Quebec-government-sponsored trade mission to Edmonton to get in on the goodies: “This is a unique opportunity for (Quebec) businesses to position themselves to establish ties to the big decision-makers of Alberta’s energy sector.” To many Albertans, this seemed to be the height of hypocrisy.

Premiers Charest and McGuinty may not have realized it when they targeted the oil sands, but they had just touched the “third rail” of Canadian federalism. And that third rail travels a well-worn path through…equalization.

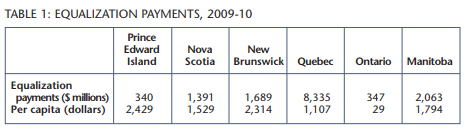

Equalization was created in 1957 to address fiscal disparities among provinces by enabling the less prosperous provinces to provide “reasonably comparable levels of public services at reasonably comparable levels of taxation” (table 1). The program is governed by a series of rules and formulas, and grows in line with the economy through a three-year moving average of GDP growth. The federal government acts as banker, by applying the formulas and distributing the funds from the taxes it has collected across the country.

For years, there have been sporadic criticisms that equalization results in higher levels of public services in the provinces that receive the payments than in those who make the payments. A recent study on the impacts of equalization promises to add a lot more fuel to this debate. In February, the Frontier Centre for Public Policy released “The Real Have-Nots in Confederation: Ontario, Alberta and British Columbia,” by Ben Eisen and Mark Milke, which has been adapted for these pages. The study compared the availability of 10 separate public services in have and have-not provinces and reported some startling findings:

There are substantially more doctors and nurses per capita, on average, in the have-not provinces than in the have provinces. Nova Scotia has 228 physicians per 100,000 people and Québec has 217 physicians per 100,000 people. The comparable ratio in the main have provinces is 176 in Ontario, 197 in Alberta and 198 in British Columbia per 100,000 people…In education, undergraduate tuition tends to be lower in the have-nots. Québec’s average tuition is $2,167, while tuition is $5,643 in Ontario, $5,361 in Alberta and $5,040 in British Columbia…Daycare spaces are more readily available in havenot provinces; a regulated space exists for 25 percent of Québec children under five years of age. The equivalent measurements in the have provinces are 19.6 percent in Ontario, 17.4 percent in Alberta and 18.3 percent in British Columbia.

The study also found that Quebec’s social services spending per capita stands at $2,342 per year, while Ontario, Alberta and BC spend $1,398, $1,592 and $1,702, respectively.

The conclusions drawn by the authors of the Frontier Centre study raise significant questions for the future of equalization. As the report argues:

- Services are not equitable between jurisdictions because donor provinces subsidize levels of government services in the recipient provinces beyond those available in the have provinces.

- Have-not provinces tend to spend more freely because their taxpayers are not forced to bear the entire cost of richer services, which undermines democratic accountability.

- Equalization provides a disincentive for poorer provinces to control spending and invest in productivity to raise economic growth.

The latter argument goes perhaps a bridge too far, at least on the productivity side, because effective social spending actually contributes to overall productivity, but the arguments about equity, accountability and spending control are difficult to dispute. And much of the proof for these conclusions can be found in the comparative percentages of provincial revenue that are derived from major federal transfers (defined as equalization plus the Canada Health Transfer and the Canada Social Transfer). The study found that in the have-not provinces, federal transfers account for between 25 percent (Quebec) and 35 percent (Prince Edward Island) of provincial revenue, while in the have provinces, the proportions are much lower, ranging from 7 percent in Alberta, to 12 percent in British Columbia and 13 percent in Ontario.

The problem for Charest and the premiers of the other have-not provinces is that the economic power shifts going on within the federation are beginning to weaken the traditional support among contributing provinces for the nationbuilding objectives of equalization. This is a significant shift. Although one Ontario finance minister famously complained in the 1880s that Ontario did not enjoy being the “milch cow” of Confederation, for the past 50 years at least, that province has embraced support for the poorer regions of the country as part of its national duty.

Until recently, it’s been the same in Alberta. Notwithstanding lingering anger over the National Energy Program, the majority of Albertans adopted a similar spirit of generosity, as their petro-tax dollars increasingly flowed east to be redistributed to the have-nots through equalization and other federal transfers. They knew Alberta was booming, and they were pleased to share the wealth with those who didn’t share their advantages. That all went sideways once Quebec and Ontario started taking shots at the oil sands.

Nowadays, it’s common to find Alberta spokespersons talking with a new edge about equalization. They are making the point that in 2009, for example, Alberta citizens and businesses paid an estimated $40.5 billion to the federal government in taxes and other payments, while getting back only $19.3 billion in federal services. Not only does that easily fund the entire $14 billion spent on equalization every year, but it’s a difference between what goes out and what comes back of $5,742 for every Albertan. And their collective response to those who question transfers tainted by GHG emissions? “Well, if you want to complain about our oil sands, you’d better expect Equalization to be on the table too.”

The coming debate about equalization will take place in a new national economic environment in which economic power within the federation has been rapidly shifting west, and is increasingly concentrated in Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia. Meanwhile, Ontario’s economy has suffered mightily from the recession, and Quebec continues to pursue a set of economic and social policies that many believe have reached their “best before” date.

It’s not just westerners who are challenging the status quo. More and more Quebecers are warning that the province needs to reconsider policies that enhance its eligibility for equalization. Former Quebec Premier Lucien Bouchard continues to question the time-honoured “Quebec model.” In 2005 he cosigned, with 12 other Quebec notables, the “Clear-Eyed Vision of Québec” document, which, among other things, called for lower public debt, an end to the freeze on tuition fees, increased investments in productivity and innovation, and higher electricity rates. None of those issues have been addressed, and they keep coming back. In mid-March, the Montreal Gazette called on the Charest government to raise the price of electricity, noting the relationship between low rates and equalization:

One reason for avoiding a real increase in rates is that that would reduce Quebec’s equalization payout. Provinces’ resource revenue is a key factor in calculating how much each province receives in equalization. So if Hydro-Québec remits more money to the government, the cheque from Ottawa would shrink, perhaps by about half as much…Talk about moral hazard! Economist Claude Montmarquette compares this to a welfare recipient refusing to seek work because he would lose his benefits if he found a job…This state of affairs invites a considerable backlash from the rest of Canada.

And respected Quebec journalist André Pratte recently weighed in with the following lecture for Premier Charest on the realities of living happily within the federation:

In Quebec, we continue to spit on Albertan oil and gorge ourselves on our supposed green virtue. This hypocrisy only creates a fury among Albertans against us, while having no impact on the exploitation of the oil sands…Another approach would consist of generating, at all levels, a dialogue with our Albertan fellow citizens. We should be interested in what goes on there, and try to understand it. In short, we need to stop turning other Canadians against us.

In fairness, it must be noted that Quebec’s March 30 provincial budget made some initial if halting steps toward addressing the comparative imbalances that cause concern among the have provinces. The budget raised the provincial sales and fuel taxes, promised a 3.7 percent increase in electricity rates (but not until 2014-15) and announced a still undefined rise in tuition fees. On the other hand, it set a goal of providing 220,000 $7 a day child care spaces by the end of this year, which will not escape notice in other provinces. And with a gross debt of $160.1 billion, Quebec now has a debt-to-GDP ratio of 53.2 percent, the highest of all the provinces.

It’s an axiom of interprovincial relations in Canada that happiness reigns when the provinces and territories are united against their common enemy (and benefactor) the federal government. At many times in Canadian history, an interfering, expansionist or tight-wad federal government has provided the glue that held the provinces together and created a common cause. That’s the case with health care financing, but the linkage of environmental issues and equalization is a new and potentially divisive development. New dynamics are in play.

And that’s why this summer’s meeting of the Council of the Federation could see some fireworks. So good luck with your first tour on the national stage, Premier Selinger. And welcome to the NHL!

Photo: Shutterstock