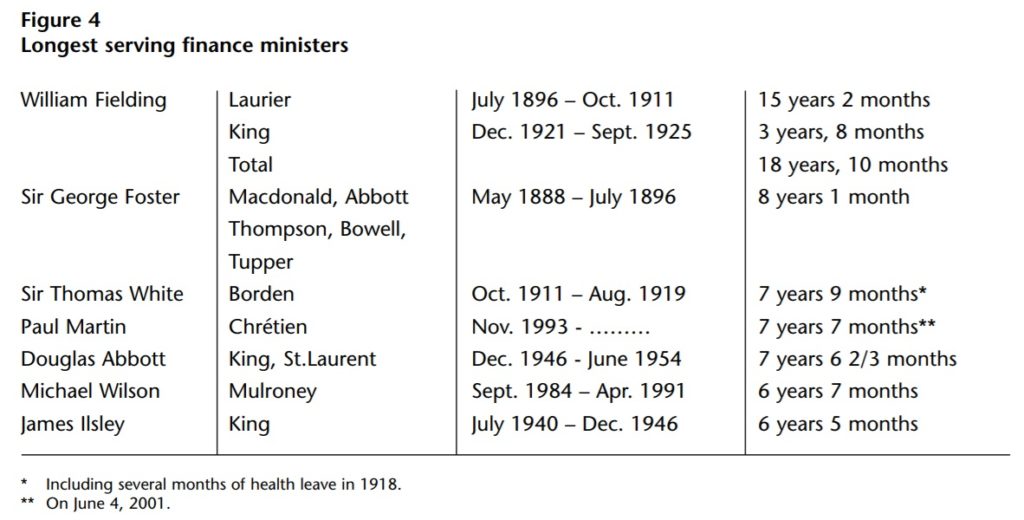

Shortly after Victoria Day, Paul Martin entered the political record books as the longest-serving federal finance minister since the First World War. Others may have survived longer in this usually thankless job. Nova Scotia’s William Fielding was finance minister for more than 19 years in the much simpler era of government between 1896 and 1925. Conservative Sir George Foster lasted a little more than eight years in office in the late 19th century, a little longer than Sir Thomas White, Borden’s wartime finance minister and father of the income tax. But few have had Paul Martin’s impact. Whether or not he ultimately reaches the summit of Canadian politics, he has played a greater role in changing the nature and operations of government in Canada than any federal cabinet minister since C.D. Howe bestrode the public stage as “Minister for Everything.”

Martin’s enduring political significance goes beyond the Canadian economy’s performance under his stewardship or his skilful leadership in eliminating chronic federal deficits during the 1990s. Rather, he has restored the Department of Finance to its position as the federal government’s dominant central agency. As the Department’s recently revamped website proudly boasts, “If it has to do with the economy, it’s our business.” But the Department’s influence goes well beyond that. Martin’s creative use of the budget and tax policy processes—and Finance’s central role in managing intergovernmental transfers—has also given it a much stronger role in influencing Ottawa’s social policy priorities by linking them with its political, economic and fiscal agendas. By defining and implementing a clear policy framework, Martin has been able to enforce a greater degree of stability and coherence in federal economic and social policies than at any time since the 1950s. At the same time, his mastery of the political side of his job has effectively redefined the process both of juggling competing spending priorities through the budgetary process and of mobilizing public support for those priorities. In sum, one of Paul Martin’s most significant achievements as minister of finance has been to restore his department’s ability to dominate the design and implementation of the national agenda.

This process is not entirely new. The implementation of Keynesian economic policies after the Second World War, reinforced by the extension of Ottawa’s wartime control over most major sources of tax revenue, resulted in more-or-less authoritative finance departments that enforced centralized control over budgetary processes at both federal and provincial levels. Fiscal centralization enabled finance ministers to create and enforce a fiscal framework for cabinet colleagues that was capable of balancing competing political and economic demands. This process helped to insulate budgetary decisions from pressures intended to serve short-term political interests, but which might not have been sustainable in the medium and long term without eroding the conditions necessary for continued economic growth. The breakdown of these institutional structures and of the fiscal self-discipline they had promoted resulted in the increasingly erratic management of tax and fiscal policies during the 1970s. A renewed commitment to these principles, underpinned by close cooperation between Martin and Prime Minister Jean Chrétien, has been a decisive factor in restoring budget balances and more coherent economic policies during the 1990s. It has also enabled Martin to accumulate the fiscal resources necessary to reassert a stronger role for the federal government in coordinating economic and social policies—despite a progressive decentralization of fiscal power which has seen provincial own-source revenues rise to 95 per cent of federal revenues in 1999-2000.

Unlike most finance ministers of recent years, Martin succeeded in defining and enforcing a political and economic strategy that not only set budgetary priorities for the government, but helped to redefine the federal government’s role in the economy and society. The government’s “Purple Book” of October 1994 spelled out what remain the core policy goals of the Chrétien-Martin Liberals:

- encouraging Canadians to adapt to new opportunities by facilitating rather than resisting economic change and shifting government income support programs towards labour market adjustment;

- helping Canadians to acquire the skills needed to compete in a changing economy;

- redefining federal priorities (“getting government right”) to achieve more efficient management of federal spending, a more flexible regulatory environment, and a more efficient division of responsibilities with the provinces;

- encouraging a more dynamic economy by fostering innovation and opportunities for trade expansion and market diversification;

- restoring Canada’s fiscal health through deficit reduction, greater spending discipline, and a progressive reduction in public debt relative to the size of the economy.

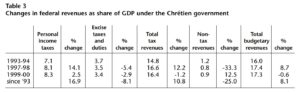

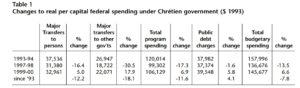

Martin’s first achievement was to reassert Finance Department control over the budgetary process and to insist on the achievement of budgetary targets as a precondition for new policy developments and a more active role for government. By insisting that budgets be based on highly conservative fiscal and economic projections, rather than optimistic economic growth forecasts, Martin succeeded in enforcing substantial spending reductions on his colleagues—and capturing the increased revenues from economic growth for deficit reduction. Although Martin has relaxed his spending constraints somewhat since balancing the budget in 1997-98, he has consistently used a share of his budgetary cushion for debt reduction— thus allowing Ottawa to preserve a degree of fiscal flexibility in the event of an economic downturn.

While these goals could not have been achieved without firm and consistent prime ministerial support, Martin’s insistence on disciplined financial management restored a basis for trust in government by those who pay for it that had been progressively squandered during the previous 25 years. Just as important, Martin has renewed the Liberal tradition that effective management is a vital precondition of being able to fulfil the good intentions that Liberals have used to justify activist government.

Martin’s policies were and are rooted in a fundamental rethinking of Canadian liberalism that emphasizes the need to make economic and social policy complement one another, rather than function in relative isolation or even at cross purposes. This vision of more focused, selective government intervention largely accepts the neo-conservative critique that governments had too often become the captives of narrow special interests—whether the producers of public service

s or client groups unrepresentative of the broader society. However, it preserves an active role for the federal government by emphasizing its part in “enabling individual choice,” “overcoming dependence” and “shared responsibility” for adjustments to a changing world as part of a new “balance” in the relationship between individuals and society, market and state.

This commitment to “selective activism” is clearly within the mainstream of international liberalism. Acknowledging the futility of economic nationalism, it recognizes that the waves of continuous economic change, spurred by globalization and the ongoing technological revolution, cannot be controlled by government fiat—except at significant risk to the competitiveness and living standards of trade-dependent countries such as Canada. At the same time, Martin’s neo-liberalism roots the legitimacy of government policies in their ability to assist citizens to adapt to changing times, to share in the emerging opportunities provided by the new economy and to extend a helping hand to those in greatest need.

Except for the crash program of spending reductions forced through as part of the government’s deficit reduction exercise of 1994-97, Martin has implemented these policies through a series of incremental policy changes and extensions. The Canada Child Tax Benefit, introduced in 1997 as part of a broader agreement with the provinces to fight “child poverty,” has been gradually expanded to become Ottawa’s third largest transfer program—increasing family benefits not just for low-income families but for most middleclass families as well. Martin’s 1998 budget packaged a series of tax and spending measures to facilitate access to education, limit the growth of student debt, and expand research funding for Canadian universities, all of which have been enriched in subsequent budgets. These measures are clearly a form of chequebook federalism intended to expand Ottawa’s direct relationship with large numbers of Canadians. However, by doing so in ways that expand the individual choices and discretion of citizens, they have enabled Martin to expand his control over the budgetary process, and to preempt the creation of new social entitlements and bureaucratic programs that could undermine the government’s broader fiscal and economic agenda.

Regular Auditor General’s reports remind us that we still live in a political culture in which political expediency and pork barrelling often trump good management practices, let alone rational policy-making. However, despite occasional reversals such as the HRDC slush funds used as a political sweetener to compensate for EI cuts after 1996, or the subsequent rollback of EI reforms announced before last year’s election, the policy framework reaffirmed in Martin’s annual budgets has imposed a greater sense of focus and discipline in federal spending than at any time since the 1950s.

Martin’s ability to combine fiscal and policy discipline has depended on three main factors: tactical skill in managing the budgetary process, his ability to mobilize support for a strategic policy vision that integrates economic and social policy goals, and the rising tide of a growing economy. Martin has effectively changed the budget process to make most incremental spending increases contingent on sufficient economic growth to exceed budgeted revenue targets. He has won cabinet (and more important, prime ministerial) support for an economic strategy that focuses most spending growth on three main targets—education and training, research and development, and health care—a strategy that enables the government to coordinate its major policy goals and stay abreast of public opinion. Health, education and research spending accounted for more than two-thirds of “new” spending announced by Martin in budgets between 1998 and 2000. By using the tax system to increase income security spending targeted at lower-and middle-income families, Martin has also diffused the political outcry that might otherwise have resulted from his diverting an average $6 billion annually in EI premiums since 1995 for other policy purposes.

By clearly linking targeted spending on post-secondary education, research, innovation, infrastructure, and income security to economic renewal and the capacity of all Canadians to participate effectively in society, Martin has been able to appeal simultaneously to traditional Liberal constituencies in the public sector, to lower and middle-income families concerned for their economic security, and to significant elements of the business community. This balancing of interests has been vital in enabling the Liberals to present themselves as a national party, despite their continuing weakness in large parts of Western Canada and Quebec.

Martin’s tactical ability to manage the budgetary process has been a vital factor not only in reducing the deficit and recording successive budget surpluses, but also in giving Ottawa enough fiscal flexibility to pursue its goals while responding to political pressures and public priorities.

Moving away from traditional ideas of budget secrecy, Martin has integrated the communication of the government’s priorities (and those of his Department) with every stage of what has become a year-round budget process.

Martin’s success is closely linked to his political skill in managing public opinion by carefully framing the policy debate in ways that have allowed him to reach his goals while forestalling competing political agendas. The old Ottawa tradition of budget secrecy has given way to “Holiday Inn budgeting—”a blizzard of trial balloons and calculated leaks intended to ensure that there are no surprises and that public opinion is properly prepared, tested and cultivated. Martin has made effective use of annual fall economic statements to manage economic expectations, outline the government’s broad priorities and solicit feedback from a wide range of interest groups through both public hearings and private meetings. These are integrated with consistent opinion polling to test possible budget messages and to identify both political opportunities and limits. In response to growing criticism of his fiscal sleights-of-hand, Martin has increased confidence in his fiscal forecasts by opening the budget process to include private sector economists. While this may not have improved their predictive ability, it has ensured that if Martin’s official forecasts do turn out to be wrong, his economic cushions are clearly visible and he has lots of company. Seen as a whole, this approach has resulted in a more open budget process, one in which both public opinion and major interest groups inside and outside are engaged while Martin calculates and defines his priorities in consultation with the Prime Minister and senior cabinet colleagues.

An important part of this process has been Martin’s tendency to build in a “consolation round” to his budget process in which he distributes the proceeds of his budgetary cushions to finance the year-end spending priorities of cabinet colleagues or to placate provincial demands for increased federal transfers. Off-budget spending increases have ranged between $3 billion and $6 billion annually since 1998— mainly financed either by revenue windfalls from higher than expected economic growth or by the reallocation of Employment Insurance surpluses and other savings to “other priorities.” In some but not all cases, these measures have been spread over several years, both to manage expectations and to “smooth” the growth of federal spending. However dubious major end-of-year spending announcements may be as a budgetary practice, Martin’s extensive use of these tactics has enabled him to allocate significant funding for his medium-term policy goals and at the same time offer cabinet colleagues what amounts to a consolation round for spending proposals that didn’t make the first cut of budgetary priorities.

Martin has also helped to redefine the financial relationship between federal and provincial governments in ways that give both senior levels of government greater flexibility in dealing with their own policy priorities, while enhancing Ottawa’s political “visibility” in the lives of individual Canadians. The decentralization of fiscal and regulatory power to the provinces since the 1960s, fuelled by the formerly open-ended federal transfers to the provinces, played a major role in destabilizing the finances of both levels of government during the 1970s and 1980s. Ottawa’s ability to control its own finances was seriously compromised by shared-cost programs that gave provincial governments an incentive to increase funding levels based on federal subsidies. Unilateral federal reductions to transfer programs, while rational from the standpoint of the government’s own budgetary management, destabilized provincial finances and prompted calls for greater provincial autonomy from federal control.

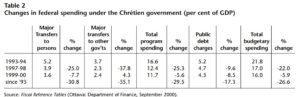

Ironically, Martin’s sharp reductions to federal-provincial transfers, an average 24 per cent cut between 1995 and 1998, have actually given Ottawa greater leverage over the provinces than it has enjoyed since the 1960s. In replacing federal EPF transfers for health, social services and post-secondary education with the Canada Health and Social Transfer (CHST) after 1995, Martin conceded greater discretion to the provinces in spending the remaining transfers. The gradual restoration of these transfer cuts has provided Ottawa with some additional leverage— particularly in reasserting Ottawa’s role in the field of health policy through the exercise of the federal spending power.

While the relationship between federal and provincial governments in setting clear and sustainable priorities for health spending still has not been resolved, other initiatives have contributed to a more rational division of labour between the two levels of government. Agreements over the National Child Benefit have allowed Ottawa to focus its priorities on income security by expanding its refundable tax credits for lower-and middle-income families, while enabling the provinces to pursue a variety of service delivery options suited to their own needs and priorities. The new “tax on income” system allows each province greater flexibility in determining its own tax rate structure, while maintaining a more-or-less common definition of income across Canada and a single tax collection bureaucracy for most Canadians.

Taken together, these achievements have helped to redefine the finance minister’s role within the Canadian political system. It remains to be seen whether they are the product of Martin’s personal political skills and his unique relationship with Jean Chrétien—so far the only former finance minister to become prime minister—or whether future ministers will have the ability and the opportunity to follow in his footsteps.

Governments’ capacity to introduce large-scale changes is often the by-product of political and economic crises. Martin and Chrétien were able to use the fiscal crisis of the early 1990s to drive through reforms to federal policies that had eluded their predecessors for almost 20 years. It is not yet clear whether, in the absence of a serious political challenge to their continuation in office, Martin and his successors can maintain the fiscal and political discipline to avoid a reversion to business as usual. If Martin eventually becomes prime minister, will he be able to find someone with the same political and communications skills to succeed him as finance minister?

Mr. Chrétien’s eventual successor will inherit a political system in which power has been centralized to a degree that many consider dangerous to the long-term health of Canadian democracy. An imperial prime ministership does allow for strong and effective management of public policy within a framework of fiscal discipline—but there is no guarantee that it will be used for that purpose. Parliament’s progressive irrelevance in enforcing democratic accountability in fiscal and other matters was clearly demonstrated in Martin’s failure in his latest economic update to provide a clear financial report for the past fiscal year—and the relatively muted public response to this omission.

Maintaining public support for these policies requires not just management, but leadership—the personal qualities that inspire others to follow, not just in their own self-interest, but in pursuit of a shared vision of the public good. In becoming Canada’s longest-serving finance minister in the era of big government, Paul Martin has provided that kind of leadership. It remains to be seen whether others will be able—or willing—to follow in his footsteps at a time when the responsible exercise of power has become progressively more dependent on the ethical compass of politicians rather than the consistent exercise of democratic checks and balances.

Photo: Shutterstock