The history of risk communication is chock full of examples where threats are ignored or downplayed (Ebola in West Africa), details of the threat are concealed (SARS), or populations are given inappropriate reassurance (Hurricane Katrina). In some cases, the opposite happens. Whether it’s to score political points, leverage budget influence, or because they simply don’t know better, authorities have also torqued a relatively mild threat into something more calamitous by appealing to our fears and anxieties (H1N1).

This wasn’t the case with Hurricane Matthew as it moved violently towards the southeastern United States, but not before exacting major destruction in Haiti and parts of the Caribbean. The storm’s tragic impact outside of the US rightly has our attention and must be the focus of international concern and action. Quite separate from that disaster, however, as the storm approached the United States, we were witness to a fascinating example of emergency communication, and one of the core risk communication dilemmas authorities face.

President Obama set the tone for the seriousness of the situation when he said something along the lines of, “If there is an evacuation order…Do not be a hold out. We can replace property, but we cannot replace lives.”

Florida Governor Rick Scott took matters to the next level, stating unambiguously: “This storm will kill you.”

The Weather Channel’s Bryan Norcross, described as a senior hurricane specialist, was even clearer in his assessment: “This is not hype…it is not hyperbole…I’m not kidding…I can’t overstate the danger of this storm…(there will be) heart breaking loss of life.”

Not to be outdone, Fox News anchor Shep Smith worked hard to further eliminate any sliver of nuance in saying: “This moves 20 miles to the West, and you and everyone you know are dead. All of you. Because you can’t survive it. It’s not possible unless you’re very, very lucky. And your kids die, too.”

Those of us working in this field spend a lot of time trying to convince decision-makers they should never downplay risk. If anything, overstating the threat is probably a better communication strategy, even if those threats ultimately don’t come to pass. On one level, this is because it’s far easier to justify an over-reaction than try to explain why you under-reacted. On another level, while over-reactions can undermine public trust and confidence, under-reactions can lead to preventable loss of life and infrastructure. Moreover – the inevitable sarcastic tweets aside – we suspect many people actually want the authorities to do the worrying on their behalf.

The biggest challenge facing emergency communicators is how to inform and warn the public about a possible threat without freaking them out. In this context there is an important and constructive role for the type of fear-based messaging that we’ve seen with Hurricane Matthew. First, fear messages serve both emotional and practical purposes. Despite the common, if misinformed, assumption that fear will lead to public panic, the most common challenge authorities face in an emergency situation is not dread, but apathy. A threat may be severe, but the public, perhaps numbed by the ever-presence of disaster imagery in their increasingly mediated lives, feels protected.

Appeals to fear are commonly and appropriately used to ensure community preparedness for near-certain hazards: a threatening wildfire, blizzard, tsunami, tornado or hurricane. Research suggests that when fear is expressed more delicately, it can be an effective motivator in cases where apathy outweighs concern, and where the public is unlikely to change its behaviour.

Indeed, those of us who study and practice risk communication warn that fear appeals should be used with great caution, as they can backfire for a number of reasons. A citizen’s sense of efficacy, we know, has two dimensions – perceived self-efficacy (ability to perform recommended response) and perceived response efficacy (belief that a recommended response averts threat). If the audience to an emergency message does not believe they are able to effectively avert the threat, then over-the-top warnings may only frustrate them and in the longer term can erode trust.

In the case of Hurricane Matthew the situation may be even more complicated, and it’s hard not to sense a measure of desperation in the statements of US officials and media commentators.

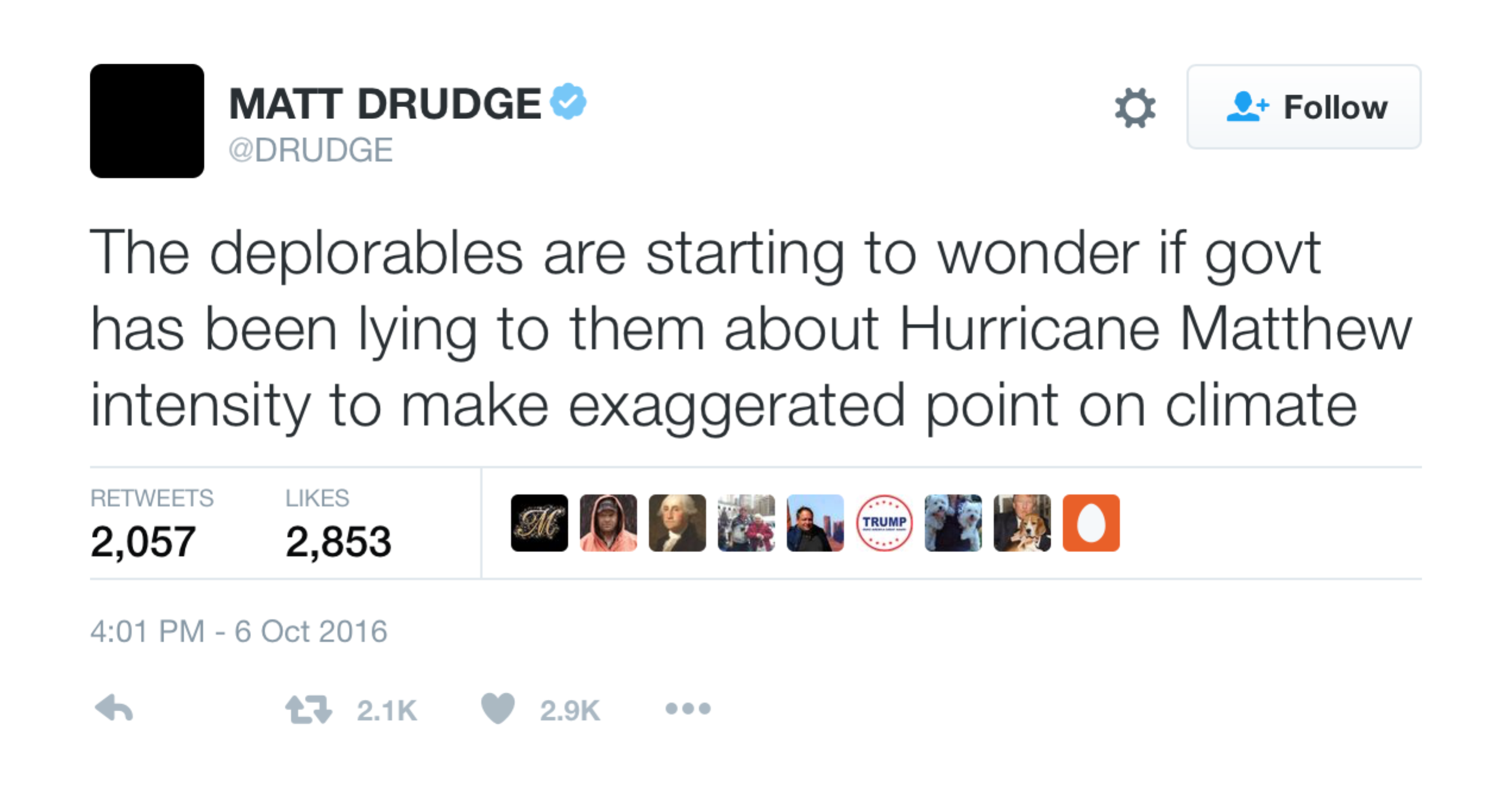

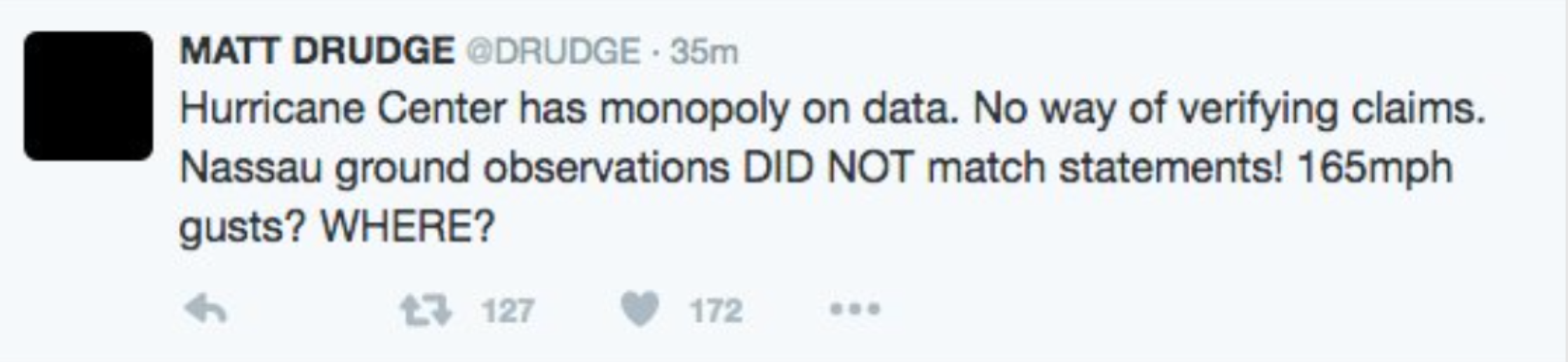

Our guess is that all those in charge have nothing but the best of intentions, to avoid needless death and minimize destruction. Surely the widely shared images of Matthew’s total devastation in Haiti also shaped the initial response of US officials, analysts and media pundits. But still, it’s hard not to suspect they already know those most at risk would have likely ignored their advice. Because on the other side of the fear and alarm, we saw in the unfolding public discourse something different and disturbing. The Conservative blogger/activist Matt Drudge reflected some of the sentiment in a recent string of Twitter posts:

Of course, it may be easy to dismiss an alt-right muckraker and the cartoon villain he supports for president as fringe whackos. But then we look to evidence like the Chapman University Survey of American Fears, 2015, which tells us that we should take these perspectives very seriously.

The survey reports that while 26.4 percent of Americans identified hurricanes as something they are afraid or very afraid of, 58 percent of respondents – far and away the highest number in the survey — signalled that corruption of government officials was keeping them up at night.

One interpretation of this data pairing: “I’m sort of worried about a hurricane…but I’ll be damned if I trust my government to keep me safe!” We saw evidence of the same dilemma during the hobbled evacuation of New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina. There were too many anecdotal stories of victims warning off rescuers with guns in hand, clearly desperate for assistance but refusing to allow authorities to provide it. It’s likely that fear based messaging is really besides the point – in these cases, trust is simply so low these groups just aren’t listening.

At one level, it’s human nature to say: “don’t say we didn’t warn you.” The problem, though, is that authorities don’t have this luxury. It’s their public duty and responsibility to help and support those who cooperate as well as those who are disagreeable.

So, what to communicate? And do fear-based messages have a role?

Obviously authorities have to communicate the information needs of those who are willing and able to follow evacuation instructions — which highways to use, where to seek safe lodging, when they can safely return to their homes. Practical, life-saving instructions are always important.

However, the more necessary target audience – and truly the key to successful emergency management – is not those who are compliant, but rather those whom President Obama described as “the holdouts.” From polio to Ebola, Zika to HIV, and from Katrina to Matthew, authorities know this communication challenge all too well. Achieving a positive behavioural change outcome from a “holdout” minority is incredibly difficult.

But emergency communicators have options. They can change the message to directly engage this group, informed by an understanding of its information needs, perceptions and concerns. For example, emergency messaging might step away from trying to scare people into action, to trying to highlight “what’s in it for them” by concentrating on the message receiver’s core interests. Or it might go further to shift from top down directives to a call for bottom up assistance by appealing not to their self interest but to their commitment to community: “we need you to do this,” “we need your help,” or, if appropriate, “we need your courage and contributions.”

Beyond a shift in messaging, authorities can also choose to change the messenger. If the holdout group won’t trust federal or state spokespersons, authorities need to identify the sources they do trust. For senior officials and organizational leaders, such an admission can be difficult, if not embarrassing. But time and again we’ve learned that local community leaders (pastors, business officials, doctors, etc.), can be exponentially more effective than federal authorities in communicating guidance during an emergency event. Of course, to say that we’ve “learned” that lesson overstates it. The same recommendation seems to come up in nearly every after-action and review report, suggesting we haven’t learned a thing.

The key is to know that whatever risk communication options are chosen, they must be informed by a foundation of evidence. If we are serious about engaging the holdouts, we need to understand them and appreciate their perspective. This takes research, which is typically not something you wait to do until a hurricane starts gathering strength off your shores.

In the case of Hurricane Matthew, we should applaud the commitment of authorities to help those at risk anticipate the possibility of a worst-case scenario. Although the impact of the storm on the United States may have been less than predicted, for the families of those who have lost their lives, and for the communities still facing danger and uncertainty, its impact has been profound. There are those who may accuse authorities of fear mongering, but we say “good for them.” Publicly addressing a worst-case scenario suggests that emergency responders and political leaders are putting the safety of the public ahead of their fear of getting it wrong, even at the risk of unnecessarily sounding the alarm.

One of the most important challenges an emergency communicator faces requires figuring out a way to get the “holdouts” on board when a serious event may threaten their lives and communities. This will take no shortage of commitment, for example, conducting required risk perception research in advance of the next high risk scenario and committing the time and resources to building trust and goodwill.

Perhaps more significantly, understanding that the people with whom you so profoundly disagree likely hold the key to your success and the fulfillment of your public service duties not only shows a dose of humility, but may also be the key to saving lives when the next disaster approaches.

Photo: EPA/Willie J. Allen Jr. / Canadian Press

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.