Ontario’s recently elected Progressive Conservative government has vowed to abandon what is termed “discovery math” and to get “back to basics.” That populist election cry resonated with Ontarians because Ontario students continue to lag in mathematics and were the only ones in the country to show no significant improvement on national tests from 2010 to 2016. Like other provinces, Ontario only has to look to Quebec for a few of the elusive answers to the seemingly perpetual “math crisis” in its schools.

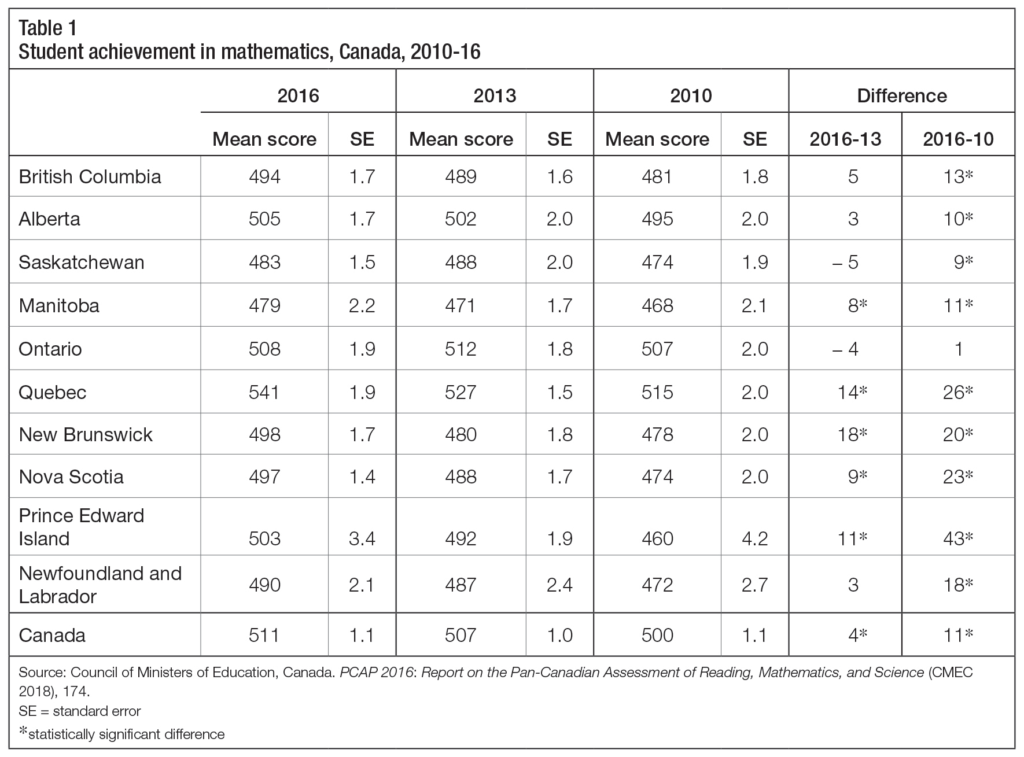

Quebec students have just demonstrated their math prowess once again. On the Pan-Canadian Assessment Program (PCAP) tests of grade 8 students, written in June 2016 with results released in May 2018, students from Quebec finished first in mathematics (541), 40 points above the Canadian mean score of 511 and a gain of 26 points over the past six years (table 1).

The latest national results solidify Quebec’s position as our national leader in mathematics achievement on every comparative test over the past 30 years. How and why Quebec students continue to dominate and, in effect, pull up Canada’s international math rankings deserves far more public discussion. Every time math results are announced, it generates a flurry of interest, but Quebec’s high standing does not appear to have encouraged other provinces to try to emulate its success.

Since the first International Assessment of Educational Progress assessment back in 1988, and in the next four national and international mathematics tests up to 2000, Quebec’s students generally outperformed students from other Canadian provinces at grades 4, 8 and 11. That pattern has continued right up to the present and was demonstrated impressively on the most recent Programme for International Student Assessment test in 2015, where Quebec 15-year-olds scored 544, ranking among the world’s top jurisdictions in education.

One enterprising venture, launched in 2000 by the BC Ministry of Education under Deputy Minister Charles Ungerleider, did tackle the question by comparing British Columbia’s and Quebec’s mathematics curricula. That comparative research project identified significant curricular differences between the two provinces, but the resulting BC reform initiative ran aground on what University of Victoria researchers Helen Raptis and Laurie Baxter aptly described as the “jagged shores of top-down educational reform.”

The reasons for Quebec dominance in K-12 mathematics performance over the past 30 years are coming into sharper relief. The BC Ministry of Education research project exposed and explained the curricular and pedagogical factors, and subject specialists, including university mathematics specialists and mathematics education professors, have gradually filled in the missing pieces. Mathematics education faculty members with experience in Quebec and elsewhere help to complete the picture.

Five major factors have been identified by leading researchers to explain why Quebec students continue to lead the pack in pan-Canadian mathematics achievement.

Clearer curriculum philosophy and sequence

The scope and sequence of Quebec’s math curriculum is clearer, demonstrating an acceptance of the need for clarity in setting out a progression of content and skills focused on achieving higher levels of achievement. The 1980 Quebec Ministry of Education curriculum set the pattern. Much more emphasis in teacher education and in the classroom was placed upon building sound foundations before progressing to problem solving. Curriculum guidelines were much more explicit about making connections with previously learned material.

Quebec’s grade 4 curriculum made explicit reference to the ability to develop speed and accuracy in mental and written calculation and to multiply larger numbers as well as to perform reverse operations. By grade 11, students were required to summon “all their knowledge (algebra, geometry, statistics and the sciences) and all the means at their disposal…to solve problems.” “The way math is presented makes the difference,” says Genevieve Boulet, a professor of mathematics education at Mount St. Vincent University with prior experience preparing mathematics teachers at the Université de Sherbrooke.

Superior math curriculum

Fewer topics tend to be covered at each grade level in Quebec, but they are covered in more depth than in BC and other Canadian provinces. In grade 4, students are generally introduced right away to multiplication, division and standard alogrithms, and the curriculum unit on measurement focuses on mastering three topics — length, area and volume — instead of six or seven. Concrete manipulations are more widely used to facilitate comprehension of more abstract math concepts. Much heavier emphasis is placed on numbers and operations as grade 4 students are expected to perform addition, subtraction and multiplication using fractions.

Secondary school in Quebec begins in grade 7 (secondaire I) and ends in grade 11 (secondaire V), and students are more likely to be taught by mathematics subject specialists. Quebec’s long-established grade 11 graduation courses, Mathematics 536 (Advanced), Mathematics 526 (Transitional) and Mathematics 514 (Basic), were tailored to different levels of ability from 1997 to 2017 and focused on “the students’ cognitive growth and the development of basic skills” as a gateway to higher-level problem solving, according to a ministry curriculum document. Under the revamped 2017 Mathematics Program of Study, mathematics was integrated into a “Diversified Basic Education” model giving higher priority to “broad areas of learning” and student engagement. While the philosophy was more holistic, the renamed courses still emphasized subject-specific content, and the final assessments remained essentially unchanged.

More extensive teacher training

Teacher preparation programs in Quebec universities are four years long, providing students with double the amount of time to master mathematics as part of their teaching repertoire, a particular advantage for elementary teachers. In Quebec faculties of education, elementary school math teachers must take as many as 225 hours of university courses in math education; in some provinces, the instructional time can be as little as 39 hours.

Teacher-guided or didactic instruction has been one of the Quebec teaching program’s strengths. Annie Savard, a McGill University education professor, points out that Quebec teachers are taught to differentiate between teaching and learning. “Knowing the content of the course isn’t enough,” Savard says. “You need what we call didactic [teaching]. You need to unpack the content to make it accessible to students.”

Teacher pedagogy in mathematics makes a difference. Outside of Quebec, the dominant pedagogy is child-centred and heavily influenced by the famous Swiss child development psychologist Jean Piaget and behaviourist theories of learning. Prospective teachers are encouraged to use “discovery learning” and to respond to stimuli by applying the appropriate operations. In Quebec, problem solving is integrated throughout the curriculum rather than treated as a separate topic. Four-year programs afford education professors more time to expose teacher candidates to the latest research on cognitive psychology, which challenges the efficacy of child-centred approaches to the subject.

Secondary school examinations

Students in Quebec still write provincial examinations, and achieving a pass in mathematics is a requirement to secure a graduation (secondaire V) diploma. Back in 1992, Quebec mathematics examinations were a core component of a very extensive set of ministry examinations, numbering two dozen and administered in grades 9 (secondaire III), 10 (secondaire IV) and 11 (secondaire V). Since 2011-12, most Canadian provinces, except Quebec, have moved to either eliminate grade 12 graduation examinations, reduce their weighting or make them optional. In the case of BC, the grade 12 provincial was cancelled in 2012-13, and in Alberta the equivalent examination now carries a much reduced weighting in final grades. As of June 2018, Quebec continued to have final provincial exams, albeit fewer and more limited to mathematics and the two languages. Retaining exams has a way of keeping students focused to the end of the year; removing them has been linked to both grade inflation and the lowering of standards.

Preparedness philosophy and graduation rates

Academic achievement in mathematics has remained a system-wide priority, and there is much less emphasis in Quebec on pushing every student through to high school graduation. From 1980 to the early 2000s, the Quebec mathematics curriculum was explicitly designed to prepare students for mastery of the subject, either to prepare for further study or to instill a mathematical way of thinking. The comparable BC curriculum for 1987, for example, stated that mathematics was aimed at enabling students to function in the workplace. Already by the 1980s, the teaching of BC mathematics was seen to encompass sound reasoning, problem-solving ability, communications skills and the use of technology. Curriculum fragmentation, driven by educators’ desires to meet individual student needs, never really came to dominate the Quebec secondary mathematics program.

Quebec’s education system remains that of a province unlike the others. While the province sets the pace in mathematics achievement, a February 2018 report demonstrated that it lags significantly behind the others in graduation rates. Comparing Quebec’s education system with that of Ontario, Education Minister Sebastien Proulx points out, is like comparing apples with oranges. The passing grade in Quebec courses is 60 percent compared with 50 percent in Ontario, and the requirements for a graduation diploma are more demanding because of the final examinations. When the passing grade was raised in 1986-87, ministry official Robert Maheu noted, the decision was made to firm up school standards. Student achievement indicators, particularly in mathematics, drove education policy; and until recently, in contrast to other provinces, student preparedness remained a higher priority than raising graduation rates.

School systems are, after all, not always interchangeable, and context is critical in assessing student outcomes. As David F. Robitaille and Robert A. Garden’s 1989 International Education Asoociation Study reminded us, education systems are “in part a product of the histories, national psyches, and societal aspirations” of the societies in which they develop and reside. Ontario, British Columbia and the other English-speaking provinces have all been greatly influenced by American educational theorists, most notably John Dewey and the progressives.

Quebec is markedly different when it comes to mathematics. Immersed in a French educational milieu, the Quebec mathematics curriculum has been, and continues to be, more driven by mastery of subject knowledge, didactic pedagogy and a more focused, less fragmented approach to student intellectual development. Socio-historical and cultural factors weigh heavily in explaining why Quebec continues to set the pace in mathematics achievement. A challenging curriculum produces higher math scores, but it also means living with lower graduation rates.

Photo: Shutterstock, by Per Bengtsson

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.