April 28, 2013 | Washington, DC

For more than 15 years now, I’ve been traveling to the developing world on behalf of the Foundation, and there is one scene that moves me deeply every time I see it. Whenever I visit a clinic, I see women lined up to get vaccines for their children. And when I talk to the women who stand in those lines, in the heat, for hours, they tell me about how far they’ve traveled to get there. They’ve often walked 10 kilometers, 15 kilometers. They’ve brought their food for the day. They’ve come with the child who’s getting vaccinated, but they’ve also had to bring their other children as well. It is a hard day for women whose whole lives are hard. But those women all walk and stand and wait, because they understand the power of science to open a path to a better life.

If love were enough to save a life, mothers wouldn’t bury their babies.

They need science as well.

Whether in form of vaccines for children, or better seeds for farmers, or effective contraception for mothers — science gives us the power we need to make our caring matter.

Our challenge is to get more science done with the poor world in mind.

There are still far too many tragic barriers to applying science to lift the lives of the poor.

We often take too long to deliver the life-saving insights of science. We often take innovations designed for the rich world and ship them to the developing world without taking into account the differing needs. And we often are stalled by behaviors and beliefs that elevate old practices over the urgency of saving lives.

One of the longest-running pieces of health research dates from the 1960s, when half of the families in a village in Bangladesh were given contraceptives, and the other half were not. Twenty years later, the families with contraception were healthier. The children were better nourished. The families had more wealth. The women had higher wages. The sons and daughters had more schooling.

Contraception is one of the greatest anti-poverty tools we have today. But the appalling paradox is that the poorer you are, the harder it is to get this tool — or to take full advantage of it — especially for women.

The barriers are enormous. Many women cannot negotiate condom use with their husbands. Many cannot openly use female contraception because the husband may want a lot of children. In Niger, I met a woman named Sadi who four times a year has to walk 15 kilometers to a clinic to get an injection, and there is no guarantee that the clinic will have the injection when she gets there.

To gain the full benefits of the science of contraception, we need researchers to travel out in the field, understand the needs, and design new tools with women in mind. We need contraceptives that can be used without the husband’s consent, that have fewer side effects, last longer, are cheaper, and can be delivered to a woman in her village or self-administered in her home.

Providing access to contraception should be a global priority for government leaders, business leaders, community leaders, even religious leaders. Contraception reduces poverty. It allows parents to choose the size of their families. It allows them to space the births of their children, and that makes it easier to give each child the food and clothing and schooling and health care and maternal care they need to thrive. The science is clear: Contraception dramatically improves the lives and well-being of mothers and children.

Bill and I believe that using science to help the poorest farmers grow more crops is the world’s single most powerful lever for reducing hunger and poverty.

Climate change will intensify the need for science in farming. Either farmers will get the benefit of new seeds that can increase yields in harsher conditions — or poor countries will face declining yields amid growing populations.

Farmers should have the right to choose the best seeds that science can offer. Whether they want seeds bred with a traditional approach, or seeds bred through biotechnology — it should be their choice. There will be spirited debate over what is best for farmers and the environment. That’s good — but the debate needs to be guided by science. The stakes are too high to allow anything less. This is not only a matter of sustaining the environment. It is a matter of sustaining human beings.

The future can be fantastic — if we use the full power of science to improve the lives of the poor. Making the case for science — for vaccines, or new seeds, or contraception — can lead us into intimate places in people’s lives. It can lead us into political storms, and can take us outside our comfort zone. But we have a duty to people who have no comfort zone. We have an obligation to them and their families to expand the reach of life-saving science.

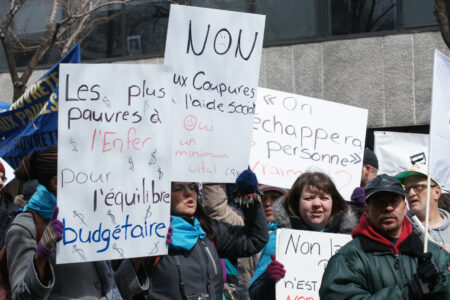

Photo: CP Photo