The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed fragilities and inequities in Canada’s innovation economy. When the pandemic began, Canada was already a global laggard in the development and adoption of new innovations and technologies, and exhibited a mediocre track record on economic inclusion and equity. As the COVID-19 crisis took hold, these long-standing weaknesses were further exposed. Without systematic and sustained efforts to improve both, we risk further entrenching innovation mediocrity and socio-economic inequalities for generations to come.

At the same time, the pandemic has prompted a willingness among citizens and policy-makers to consider a wide range of options for a post-pandemic recovery, including rethinking our approach to innovation and inclusive growth. We have a chance to lift the Canadian economy out of its low innovation equilibrium and in ways that provide more people with opportunities to participate and benefit.

But we need a clearer picture of exactly who is participating, who benefits, and how different sectors and actors are faring to inform decision-makers in industry, government and civil society about where we should focus our resources and efforts.

As we reflect on different recovery paths and destinations, we must also consider what data we need to collect, analyze and share in order to assess whether we are realizing the economy and society we want.

Innovation and distribution before COVID

Canada’s innovation performance has been weak for decades. Despite success in educating highly skilled and creative people, generating world-class research and producing new ideas, Canadian firms have not been able to draw on these strengths to develop and commercialize new products, services and processes.

Canada has consistently performed poorly on business spending on research and development, technology adoption, productivity and patent generation and protection. Even in the few regions where the technology sector is growing, Canadian firms tend to lag global peers on both the production and adoption of technology and other innovations. This inability or unwillingness to innovate in light of such vast potential has led some scholars to speak of Canada’s “low-innovation equilibrium” – that is, Canadian firms’ tendency to rely on technologies and equipment developed abroad rather than making investments to develop, use and sell home-grown innovations.

Alongside our disappointing performance in innovation is a lacklustre record on inclusion and equity – especially for women, immigrants, people of colour, people with disabilities, and Indigenous peoples. Recent analysis by the Brookfield Institute for Innovation and Entrepreneurship shows that women are nearly four times less likely to be employed, and earn $7,300 less, than men in the technology sector, despite being more likely to hold a university credential. Minority workers (except for Filipino and Black workers) are more likely to be employed in the tech sector than non-visible minorities but earn, on average, $3,100 less than non-visible minority tech workers. For others the situation is even worse. Tech workers who identify as Black earn $16,400 less than tech workers who do not identify as a visible minority.

Looking at the economy as a whole, Canada is an exceptionally wealthy country but the distribution of income and wealth across the population are uneven, and poverty is a persistent challenge. On income inequality, Canada fares somewhat better than the United States, Australia and the United Kingdom, but much worse than Denmark, Finland, Norway, Belgium and other European countries. After rising from the early 1990s to the early 2000s, income inequality in Canada has entrenched itself at a higher rate than in the 1970s and 1980s.

That was before COVID.

Known and unknown impacts of COVID

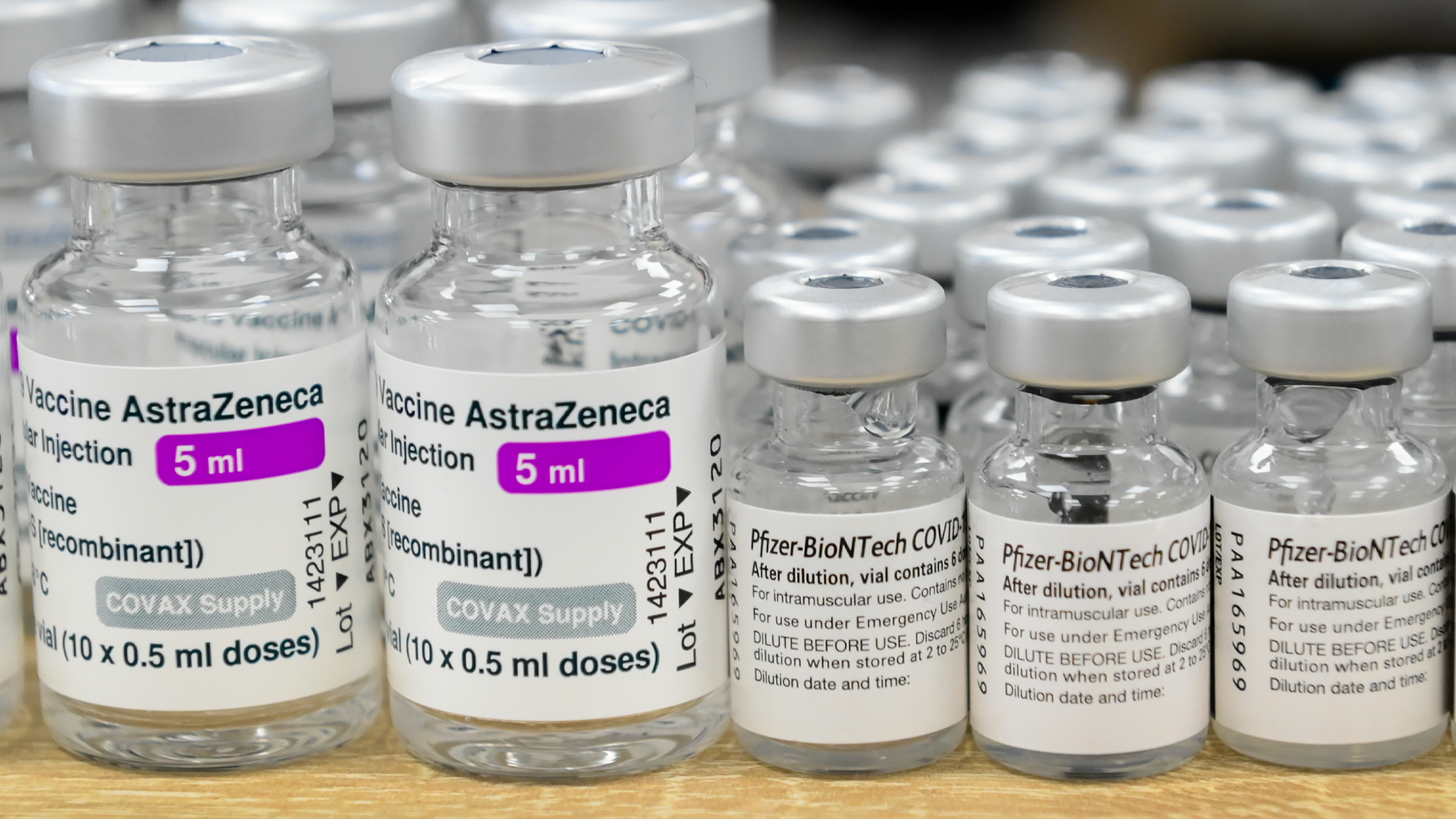

The pandemic and economic crises prompted extraordinary efforts among some of Canada’s innovators. Some manufacturers re-purposed their facilities to produce health equipment and other critical goods. Innovation Canada re-oriented its “entire portfolio” to focus on “helping Canadian businesses provide innovative medical and non-medical products and services for the COVID-19 crisis.” But it is not clear what impact these efforts will have, nor whether similar initiatives could help lift Canada’s innovation performance when a recovery begins. Our existing ways of tracking innovation are not up to task.

Meanwhile, it is not clear how these sorts of initiatives will help the many workers who are excluded from participating in, and receive few direct benefits from, the innovation economy. Many low-wage workers have lost their jobs, while others deemed “essential workers” in health, retail and service occupations face a high occupational risk for contracting COVID-19 while continuing to earn low wages.

Miles Corak, professor of economics with The Graduate Center of the City University of New York, notes that while job losses among managers and those in professional, scientific, or technical jobs amounted to “decimal point dust”, COVID “wiped out 20 years of growth” in accommodation and food services in the first month alone.

Economist Armine Yalnizyan characterizes the economic crisis as a “she-cession” in which women have experienced higher job losses because they tend to be employed in sectors that have been hardest hit – including education, child care, retail, accommodation and restaurants. Indeed, the economic effects of COVID fall disproportionately on workers in low wage, precarious occupations who are often women, immigrants and people of colour – at least according to our limited data.

Current indicators of economic well-being fail to give us a clear and timely sense of how different demographic groups are faring. We have some good snapshots and analysis, but there is so much that we don’t know and will need to know to plan and track a recovery that is both strong and inclusive.

Recovering well and measuring what matters

The pandemic and economic crisis have revealed that Canada needs to improve both on innovation and in ensuring that all people have opportunities to participate in and benefit from the innovation economy. Enhancing equity in economic participation and distribution is both the fair thing to do and a strategy for improving innovation performance itself. Moreover, more equitable inclusion and distribution of benefits can better insulate people from the effects of future health or economic crises – which will lower the individual and social costs of such crises.

In order to plan and track the progress of a more inclusive innovation economy, however, we need to improve how we collect, analyze and understand the implications of data on innovation and inclusion. We need indicators with finer granularity to complement conventional indicators like GDP growth and productivity.

We need more, and more timely, data that tell us about the distribution of growth and prosperity; the demographic mix of employment in innovative sectors; the extent to which income, inequality and poverty track gender, race, (dis)ability and other characteristics; and about access to technologies necessary to participate in the economy, society and – as the pandemic has revealed – education. And we need these data collected in ways that allow us to benchmark Canada’s performance against its current state and compare to peer countries in the OECD.

There are some concrete and easy steps that could get us closer to what we need. First, the Survey of Innovation and Business Strategy – an important source of data on innovation, entrepreneurship and technology use in Canada – should be conducted more frequently, perhaps annually or bi-annually, instead of the current three year cycle. It should sample enough firms to allow for better regional analysis and it should include one or more questions about the gender and racial make-up of firm owners and operators.

Similarly, Statistics Canada’s data on research and development personnel – a useful indicator of innovation capacity and activity – should collect information on gender (something that other OECD countries include) and other demographic characteristics, as well as more timely sectoral and provincial data.

Third, the regular Labour Force Survey would be even more valuable to our real-time understanding of economic well-being if it included questions about the labour force status of people with disabilities, in additional to its already helpful lenses of region, gender, educational attainment, immigration and – as of July 2020 – race.

Navigating to the world we want

While the pandemic has exposed Canada’s vulnerabilities and growing inequality, it has also opened a window of opportunity for creative policy action. We have an opportunity to define what kind of society we want for ourselves and our children. We envision a Canadian economy and society that is more innovative and prosperous, and in which all people have opportunities to participate and benefit. With that as our destination, we need both a map with which to navigate and data that are more comprehensive, accurate and timely to ensure that we are steering in the right direction.

This article is part of the Building a More Inclusive Innovation Economy After the Pandemic special feature.