The problem with low relative productivity in Canada and its relationship with innovation has been discussed at some length amongst policy strategists. One might observe that most of these discussions have been tactical in nature and have greatly contributed to the understanding of the innovation chain within the Canadian economy. Despite the recognition of the critical impact that competition has on innovation, much of our national policy discussions on innovation focus on “downstream” policy and program activity. This is essential to ensure that we are having maximum impact from these interventions (and I will have more to say on this with colleagues in a forthcoming report). But we also have to focus on the “upstream” within the innovation chain: competitive intensity. It is the elephant in the room (figure 1).

It is well known in quality process management that it is far more effective to solve issues as they occur, or upstream. Solutions later in a process are more expensive and less effective. The same may be true for policy development. We may not be effectively using our time and resources by focusing too much on “downstream” fixes instead of solving the problem upstream at its core. See, for example, The Canadian Council of Academies (CCA) Innovation Report discussion of the low effectiveness of down-stream policies for the Pharmaceutical industry. As with managing other processes, having knowledge of the cost saving of intervening at various stages of the innovation chain would motivate policy-makers to seek solutions farther upstream despite the larger obstacles that may result.

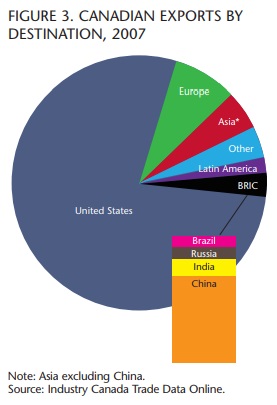

Recently, the Institute for Competitiveness and Prosperity (ICP) reported that the “cost” of low productivity to all levels of Canadian government in lost tax revenues was approximately $112 billion per year. Figure 2 indicates the type of prosperity increase that Canadians would enjoy if they closed the productivity gap with the United States.

In the early 1980s, GDP per capita in Canada was $2,700 behind that in the United States. But since that time, our growth has lagged US performance. In 2009, GDP per capita in Canada was $9,200 below that of the United States. In 2010, the gap was virtually unchanged at $9,500 (figure 2).

We will not review the linkage of competition with innovation which drives productivity. Others such as the 2008 Competition Policy Review (CPR) panel, the 2009 CCA Innovation Report or the 2011 ICP Report have reviewed this relationship extensively, and we will consider this a foundational principle. We will review the state of competition within Canada by sector, and the history of how the country arrived at the current situation. We will then discuss some policy recommendations that will optimize the country’s economic performance, as well as some structures for the country that will assist with implementation of these policies over the long term.

The solution to increasing our competitive intensity is conceptually quite simple, but it is difficult to implement. We should have more policy thinking on how we can open up more sectors of our economy to fair and open global competition. We should also have an advocacy organization to consistently ensure that the policy implementation is fair and timely and in the interests of all Canadians. As we have seen from the past 30 years of policy debate, this is much easier said than done. Let’s examine the underlying reasons for this policy failure and discuss some steps that we can take to move the debate to where it needs to be and not stuck where it has been.

In the early 1980s, GDP per capita in Canada was $2,700 behind that in the United States. But since that time, our growth has lagged US performance. In 2009, GDP per capita in Canada was $9,200 below that of the United States. In 2010, the gap was virtually unchanged at $9,500.

The transition to a global marketplace has been underway for several decades around the world, and this has inserted a particular urgency into our productivity debate. We are not in a static global economic situation. Rather, we are in a time of great change, and failure to change along with the global situation will result in a diminished relative standard of living for Canadians.

In 2007, emerging economies produced just over half of world output and accounted for more than half of the increase in global gross domestic product. These economies are rapidly becoming a major force in the world economy.

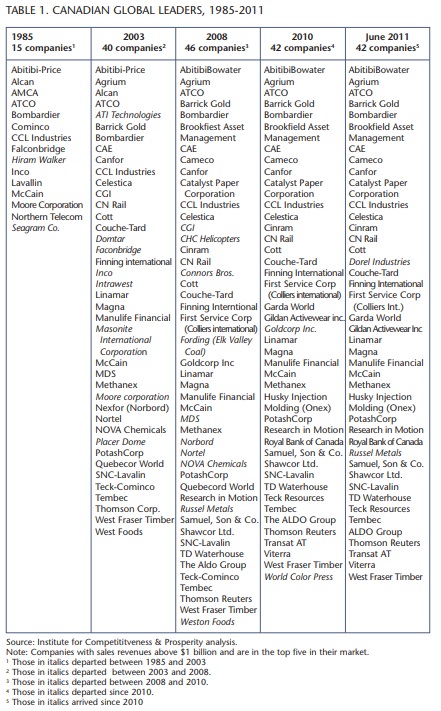

Canada’s primary trading partner is, and for the foreseeable future will continue to be, the United States. But growing markets in the expanding European Union, South America and Asia present new opportunities, yet Canada has a small fraction (3 percent) of its current exports destined for BRIC economies, as shown in figure 3.

The current state of competition in Canada has been influenced primarily by transitions in the economy, created by privatization of Crown corporations and free trade. Canada has a variety of legislative and structural elements that restrict competition. Canada has a multitude of laws and regulations governing ownership in specific sectors, as well as a number of company-specific statutes. Many company-specific statutes had their genesis in the mid-1980s to early 1990s, when they were enacted for the purpose of privatizing former Crown corporations such as Air Canada, Petro-Canada and the Canadian National Railway.

With the negotiation of the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement (FTA) and then the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), Canada underwent a further restructuring, becoming a continental market with some protected sectors that were primarily driven by social and sovereignty concerns. These concerns arose from the asymmetry of the markets being integrated (United States and Mexico) since Canada was less than 10 percent of the combined continental market. With the alignment on a continental basis as the national focus, we reduced our global orientation just as the BRIC countries were experiencing the start of substantial growth in their markets. In the previous generation, NAFTA made a lot of sense, given the reliable access it provided to the world’s largest open market. In effect, we placed most of our bets on that one market, and this created wealth opportunities for a generation of Canadians.

Even with sector protections, we cannot stem the tide of global competition for long. The cruel irony for our protected domestic industries is that they will be at a substantial disadvantage in scale and productivity when the time comes that the flood gates open fully to global competition. We need to adjust our competition policies soon, or these Canadian-based firms will be hopelessly behind the learning curve and will simply be acquired, with little chance to become global champions. The single most effective way to “encourage” firms to continue to change and evolve is to expose them to increased competitive intensity in a thoughtful manner. It may be in our interest to remove some of the sector protections negotiated within NAFTA, as the long-term harm to Canada may be greater than any short-term benefit that we believe we enjoy.

Canadian firms that compete in open global markets have responded to these challenges by casting aside the traditional paradigm of firms offering finished goods produced in a country for sale domestically or across a border. Instead, more firms now seek to organize their activities or position themselves within “global value chains.”

We are a small economy, and focusing on the biggest and fastest growing market in the world 25 years ago made good economic sense and was good policy. Canadians benefited from this wisdom for an entire generation. However, things change and the economies within the BRIC countries are growing into the largest part of the global market at a rate that is more than double that of the developed world economies. Our exposure to the largest part of the world market in the future is less than 3 percent of our total exports today. How should our sector orientation change, given these new circumstances? Is the original policy rationale that created these sector regimes still valid in the global context or even practical within the reality of the global information system?

The transition to a global marketplace has been underway for several decades around the world and this has put a particular urgency onto our productivity debate. We are not in a static global economic situation. Rather, we are in a time of great change and failure to change along with the global situation will result in a diminished relative standard of living for Canadians.

In the CPR report of 2008 on Canada’s global competitiveness, the six sectors that were identified as lacking some degree of competitive intensity when compared to global markets were financial services, telecommunications, broadcasting, transport, uranium, and culture. All of these sectors are governed by some form of legislation that was by and large last updated a generation ago — an artefact of a previous era’s policy approach to matters such as NAFTA. These six sectors, which received the most protective legislation, were the ones that were most critical to Canadian culture and sovereignty. These sector regimes were created and implemented prior to the adoption of the Internet and the rise of global trade and have not been updated to reflect their impact.

The issue with these protections is that they do not have an isolated impact on one segment of the economy, but rather they impact most of the economy. These sectors were protected because they were in effect the enabling or infrastructure segments of the Canadian economy. Therefore, if there is a negative impact on productivity in these sectors, it is amplified throughout the entire economy. Consider, for example, the widely reported OECD report on wireless costs by country that notes a higher wireless cost in Canada. This higher wireless cost has the potential to ripple through the entire economy since virtually every segment of the economy is engaged in mobile communications. One can speculate that everything from food production to professional services is impacted by organizational methods that make use of the latest enabling technology such as wireless to drive productivity. Strong relative productivity cannot be achieved with relatively inferior enabling technology.

When we consider the many tactical policy elements related to innovation, we focus on business expenditures on research and development (BERD), global trade and firm size. These are downstream output indicators and not upstream inputs that we can more effectively control. We concentrate on a direct causal relationship, yet we are not satisfied with the effectiveness of the results of these downstream policies implemented to resolve our low innovation performance. It may be that the source of our low productivity is much farther upstream. An examination of some of the output elements may be useful to determine a common input upstream. We will consider three commonly cited elements: global trade, productivity and ambition.

The lack of strong relative growth by Canadian firms into the developing economies of the world is as troubling as it is perplexing. Canada has substantial cultural Diasporas from all of these regions of the world and we should be well suited to take advantage of these growth opportunities.

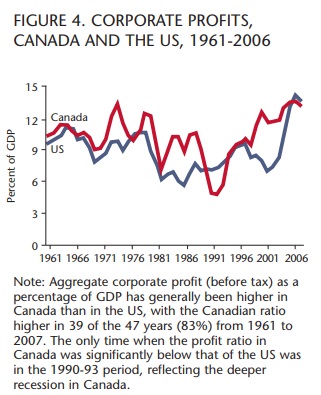

It may be that the sectoral regimes have not only protected these sectors from competition abroad but have motivated these sectors to not compete abroad lest they are exposed to harsh competitive intensity and/or the opening of the domestic market. Despite their age and relative size, none of our telecommunication companies and none of our broadcast companies are on the list of Canadian global leaders as published by ICP in June 2011(table 1). Have we in fact motivated these companies to remain domestic while the remainder of the world has encouraged its companies to become global? Prior to NAFTA, some of Canada’s largest domestic companies were true global traders and had a much more global orientation. Companies such as Bell Canada actually had substantial assets and operations outside of Canada.

It is interesting to note that in the table of global leaders from the ICP June 2011 report (table 1) fewer than 10 percent of the global leaders in Canada originate from within the protected sectors. Despite being among the largest firms in Canada, these domestic participants are not motivated to go global.

If we examine the list of Canadian global leaders, it is clear they became global leaders because they had to have a global orientation to survive, since the vast majority did not benefit from a protected domestic market or sector regime. Our current sector regime policy may inhibit expeditionary thinking. Canadian executives are not born with an ambition to stay at home, but the sector regimes may be motivating them to do so.

In terms of global competition within a global value chain, let’s consider a Canadian-headquartered international company operating throughout the world. Creating such a firm is one of the aspirations of our current policy strategy. Given the restrictions on the key enabling sectors, it means that Canadian-based telecommunications, banking, and transport are not possible for a Canadian firm on a global support basis. This increases cost through duplication and reduces the incentive for a Canadian multinational to locate its headquarters in Canada, since it does not have true global support from key infrastructure sectors within the Canadian economy. This relatively inefficient or absent infrastructure support for an international headquarters function may be inhibiting the growth of global leaders in Canada.

How do we motivate an increase in our global orientation? In the past generation, we used NAFTA as the method of conducting a continental market strategy, and now we must shift to a vehicle that enables a global strategy. We need a series of bilateral free trade agreements to open up our markets, including a selection of our sector regimes, and encourage our businesses to go abroad in search of larger markets where they can achieve scale and increased productivity. The current Canada-EU negotiation is an opportunity to define this new global trading strategy.

Removing the sector regimes and exposing our domestic firms to global competition is not a panacea, though some would argue that exposing our infrastructure sectors such as banking also exposes us to international contagion. This is a dilemma, and we cannot expect to have this both ways.

In banking, we congratulate ourselves that we escaped the global contagion. However, while it leaves us with a relatively sound domestic market at the moment, does it equip us for the future global market? Is it better for Canada to have a collection of smaller regional players unique to Canada, such as our banking system, or to have a collection of larger global players active in the Canadian economy that we would hope includes one or two Canadian-based firms?

Estimating the cost of reduced productivity is an essential component in any effective policy debate. Defining the opportunity cost may create enough momentum to challenge the status quo within Canada. We need to determine this amount so that we can have a more complete debate about the public policy benefits of a particular sector regime, and about the changing nature of the cost of maintaining these sector protections of the lower productivity relative to the United States. For example, restricting broadcast and telecommunications in the 1980s with the Broadcasting Act and the Telecommunication Act occurred when the impact on the economy for those two sectors was very different than it is today. Digital data that carries a TV signal or a phone call is the same data that enables a purchase order or an engineering drawing for a company participating in a global value chain. We can no longer create “surgical” policies that impact a specific sector, as they are now interrelated.

The lack of strong relative growth by Canadian firms into the developing economies of the world is as troubling as it is perplexing. Canada has substantial cultural Diasporas from all of these regions of the world, and we should be well suited to take advantage of these growth opportunities.

Exhortations from well-meaning policy participants that “industry should be more productive” or that “industry should do more R&D since the OECD says that you should” do not resonate with executives that manage firms. The motivation to be productive and to innovate is a primal one related to competition and the need to survive against another market participant. If we want to have better productivity in our economy, we cannot “suggest” to our executives that it would be a good idea. Instead, we must “force” these firms to change and become more productive by increasing the competitive intensity. The CCA report on innovation measured rates of R&D and productivity for sectors in Canada that did not have sector regimes. The report determined that the Canadian firms had exactly the same R&D investment ratios and productivity rates as their international counterparts. No productivity problem here. Is this a coincidence or does competitive intensity exactly correlate with innovation and productivity?

Productivity by sector in OECD or other comparisons only tells part of the story. Most likely the productivity comparisons in some enabling technology sectors have a further and more damaging relationship to the overall productivity numbers of the country and can further obscure the causal relationship. Consider mobile network costs. If we think of mobile communications as just being cell phone usage, then the productivity, impact is small for enabled sectors. But if we go beyond conversations and consider the increasing use of smart phones and tablet computers to drive business productivity we have a much greater influence on the economy. If the mobile network in Canada is not delivered as efficiently in global terms, the rest of the economy is negatively impacted. If we permit suboptimal productivity in one sector, such as telecommunications, we can assume that there will be a negative spillover impact into the rest of the economy. Manufacturing or services sectors may appear to be lacking in productivity or investment in ICT when the issue may in fact be occurring in an enabling sector. Similar examples have been cited for the impact of low competitive intensity in air transportation and the cost (and, most importantly, the ease) of global travel. For example, it would be difficult to have trade with Korea if major Canadian cities had limited or no access to direct flights to Seoul. The impact of low productivity in the sector regimes may have far-reaching consequences beyond the original sector.

If there is one single economic lesson about the most effective way to create wealth from the past century, it is that open market competition is the most effective and efficient basis for the economy of a nation. We would be wise to remember this lesson. With the globalization of finance and investment, Canada removed all restrictions of domestic setasides by the country’s largest pension funds. This should have motivated all Canadian firms to achieve the same relative productivity as their counterparts throughout the world, as they are all competing for the same investment dollar, and therefore must achieve competitive returns on investment. This did not happen. Part of the reason is that domestic firms can still return a competitive return on investment by raising prices in relatively less competitive markets and thus increase revenues. The sector regime firms have no incentive to be as cost competitive or productive as other firms exposed to global competition since they can still achieve competitive return on investment (ROI) by raising prices.

This indicates that the behaviour of Canadian executives is very efficient and rational. Recent statistics from the OECD show that returns on Canadian equities were similar or better than others within the OECD. Canadian executives are not motivated by capital returns competition to drive their costs lower as much as their counterparts globally, since they have the power to shape the top line through less intensive market conditions. Other studies have shown (CCA) that Canadian firms enjoy relatively higher rates of profitability than their counterparts in the United States.

The problem is not the bottom line, but rather how we get there. We use de facto monopolistic or oligopolistic pricing power within sectors to hide the lack of productivity in the delivery of the goods and services of the domestics. This is the “hidden tax” or GDP burden that all other Canadian firms that are in global competition must bear.

Currency rates have also influenced productivity. In the previous decade, when our dollar was valued as low as 63 cents per US dollar, some Canadian companies grew complacent and did not have an incentive to invest in productivity, given their relative advantage that they enjoyed on the currency exchange. Canada enjoyed a large trade surplus, as the advantage went to Canadian exporters. The increase in our dollar relative to the US dollar occurred so quickly that firms have struggled to make the necessary adjustments to their operations at the same pace, and some have not been able to cope. Now, with the exchange rate above parity, the cost advantage is gone and Canada’s poor productivity performance is exposed. This will remain as a major challenge for the Canadian economy, since the currency rate is being influenced by continued global demand for resources. This is a dilemma for the non-resource exporting segment of the Canadian economy, since the increased rate provides no “performance release valve” that a country would normally have with a reduced currency to offset any shortfalls in productivity. This is a “perfect storm” situation for global competitors based in Canada, and in particular for the manufacturing sector.

Much has been written about the lack of our national ambition to succeed or be entrepreneurs and win on a global basis. Similar doubts were expressed about our athletes at the Vancouver Olympics. The “own the podium” strategy was a great success, and Canadians proved that we could compete and win with the very best in the world. This has also been our experience with our soldiers in Afghanistan. Their attitude and conduct showed that Canadians were capable of performing at a high level in the most severe of conditions. The economic data also indicates that Canadian firms driven by Canadian executives have shown repeatedly (and, according to table 1, increasingly) that they can compete and win on a global scale. We have increased our global leaders from 15 firms in 1985 to 42 firms in 2010.

What are we indicating to management aspirations in the country when we create regimes that protect large sectors of the economy? Are we telling our best and brightest that they should limit their aspirations to within the country only, and that they need protection from the “barbarians” outside our borders? Are we giving these very capable executives the incertive to play “the domestic game” with government agencies that regulate what might be better operated in the free market. For domestic players, playing the game sometimes means that they must subsidize low population density areas with the same quality and quantity of services as an urban area. What makes good social policy does not necessarily make good business policy. This places dysfunctional demands on firms, and leads to even lower productivity. The sector regimes may be forcing a lower productivity from the domestic players as part of the “bargain” of limited market competition.

If we change our sector regime policy, we will change the attitudes of the executives. We should reject the notion that Canadian executives do not have an entrepreneurial attitude. In fact, the data in figure 4 from the CCA report suggest that Canadian executives are very smart and play according to the rules of the game provided by the various sector regimes, and they profit from doing so. Canadian executives and the firms they lead have become very good domestic competitors and make more returns than similar US firms. Why would they be interested in global competition when their high profitability rates may come under increasing pressure?

If we choose to open sectors up to global competition, we also need to ensure that once exposed to global competition our domestic firms can survive, catch up and thrive. To do otherwise is not in the interest of Canadians. What do we do about this?

Canada’s telecommunications policy and regulatory frameworks were subject to an extensive review in 200506 by the minister of Industry’s Telecommunications Policy Review Panel (TPRP). The TPRP received almost 200 written submissions and drew on the results of extensive consultations with stakeholders and experts in Canada and from abroad. The TPRP’s final report, issued in March 2006, concluded that liberalization of the restrictions on foreign investment in the Canadian telecommunications sector “would increase the competitiveness of the telecommunications industry, improve the productivity of Canadian telecommunications markets, and be generally more consistent with Canada’s open trade and investment policies.” The report detailed an evolutionary process in which the domestic players were allowed to merge and achieve global scale, in anticipation of the entry of major international competitors into the domestic market.

In other words, we should allow the domestic players to consolidate and build scale from which they can compete globally. Global players will eventually fill the competitive void left by the merger of domestics. Europe has many sectoral examples of this process over the past two decades. It is effective and fair, and it works. The same can be done for other sectors. In the financial sector, the CPR panel recommended maintaining the widely held rule but also allowing banks and insurance companies to integrate so that they may be more productive and achieve global scale. Again, provided that there is open international competition, innovation and productivity will be preserved.

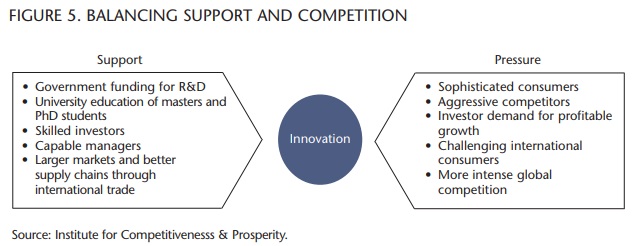

Taking all these factors into account, we need a structure that provides a balance between support and pressure, as noted in the ICP June 2011 report, and shown in figure 5.

Regardless of sector, limits to both scale and competition can be problematic for small economies. Since Canada represents less than 3 percent of world GDP, reaching the scale of the world’s largest firms will depend on how well Canadian firms fare in the contest to acquire other firms. If we do not motivated them to do so early in the game, they will have no opportunity later.

There has been no regular or comprehensive public review of these sectoral restrictions for some time. Each sectoral regime was established to address particular policy objectives, emerged at a different time, and has undergone varying degrees of regulatory and policy changes over the past three decades or so. Each of these sectors is heavily influenced by technological change and globalization, and with few exceptions (telecoms and banking) there have been no formal reviews and updates to legislation and other structures within the Canadian economy to reflect new responses to these global changes. Remember that the Telecommunications Act and the Broadcasting Act were written prior to the emergence of the Internet which has completely transformed both sectors.

Why has Canada not adjusted its competition policies further? Consider our cultural industries — we seek to protect a Canadian identity that has rapidly transformed and in so doing hurt our ability to take advantage of the global opportunity presented by the existence of the “reverse Diaspora,” particularly from the BRIC economies, within Canada. As the CPR report noted, we seek to prohibit book production and sales, yet we have an explosion of online book resources that render the previous policy obsolete. We have expended an enormous amount of policy time and capacity building on a specific area which is no longer relevant. Buggy whips come to mind.

This is a clear indication of the lack of innovation at the government level to move upstream in our policy interventions. The OECD has remarked in several reports on sector regime impacts on productivity, and observes the “symbiotic relationship” that naturally occurs between the regulated and the regulator — they need each other to survive. This continues long after the rationale for the policy no longer exists.

Why do we not have a more complete discussion about innovation in Canada? Why do we continue to regard productivity as simply working harder for less? Part of the reason is that the benefits that accrue from productivity are generally measured and regarded at the macro level alone. The problem with this in a democracy is that it typically means there is no universally regarded “burning bush” issue that the majority can support. This innovation/competitiveness debate between winners and losers in Canada is tilted toward the losers, since in our society they form into a small and cohesive advocacy group. This group has great power in the court of public opinion and tends to do well in media, as compared with an uncoordinated “silent majority” that does not enjoy such cohesion. A very loose collection of somewhat interested parties is always drowned out by a small tight motivated group that is threatened with possible extinction. Thus the majority lose. There is no organization in Canada that can advocate on behalf of competitiveness as a foundation principle for a successful economy.

Effective policy must always be accompanied by an effective process to ensure implementation, particularly over long periods of time. This means that any policy that seeks to increase competition must also be accompanied by an effective implementation approach.

Another factor for a council or body to promote competition is that the basis of competition is being innovated continuously. By definition, in a functioning market, participants are rewarded for innovating change that leads to productivity, which is rewarded by wealth creation. Only a standing body can assist with policy implementation, since any current thinking on innovation policy will be out of date in a short period of time. Only a process that is contained within an organization to dynamically and continuously refine the economy to maintain competitive intensity will work in the long term

Canada can achieve great progress with innovation and productivity if there is a desire to keep competitiveness as a foundation policy. It is worthwhile to consider the CPR report comments on a Competitiveness Council:

“By itself, competition law enforcement without supporting policies and institutions to promote competition is insufficient to realize the economic benefits of competitive markets or innovative and efficient businesses. The concept of competition and the value it has for our society is not fully realized or widely appreciated by Canadians.”

Other countries similar to our own have faced this situation. Other nations have used other institutional approaches to strengthen competition advocacy. In some countries, competition advocacy institutions foster market integration in a federal state, eliminate special rules and exemptions that blunt the impact of competition and promote greater adherence to competition values in regulatory decision-making.

We seek to prohibit book production and sales, yet we have an explosion of online book resources that render the previous policy obsolete. We have expended an enormous amount of policy time and capacity building on a specific area is no longer relevant. Buggy whips come to mind.

Some examples are the following:

- The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, the US Federal Trade Commission and the Irish Competition Authority, among others, have powers to conduct studies of industry sectors and the interaction between government regulation and economic performance.

- Australia has two institutions that participate in competitiveness matters, the National Competition Council and the Productivity Commission, which conducts in-depth studies of competitiveness issues.

- The European Commission is responsible for enforcing rules on discriminatory state subsidies and liberalizing former state-regulated or controlled sectors such as transport, energy, postal services and telecommunications. It also undertakes market studies and approves new regulations following a competitive assessment process.

The EU tackled this problem by by establishing the competitiveness commission and giving it the mandate to advocate with sufficient budget that they are able to go into great detail by sector. They found that each sector review was the only way to provide the focus needed to overcome the specific advocates of a historical way. As Canada contemplates free trade with the EU we would be wise to learn from their economic example. As an example of the level of detail engaged by the EU, there have been debates in the European press over the “Polish plumber working in Paris,” complete with imagery of a plumber coming to France to take the job of a Parisian plumber. Europe, which has significant and historic cultural history, was able to overcome these political divisions by creating an advocacy group that drove competition on behalf of all citizens. Canada would do well to establish a similar organization that speaks on behalf of all Canadians for the benefits of productivity and innovation, to overcome the self interests of the “losers” in the outcome of the policy decision. It has been remarkable to witness the transformation of Europe within the EU over the past generation as they have overcome huge structural and cultural obstacles to establish an economic union based on competitive principles. They did it, and so can we.

While these examples highlight the importance that other industrialized countries place on a dedicated focus on competition, the CPR did not recommend that Canada should directly mimic any single country’s model. Other countries have benefitted from the presence of a dedicated competition advocate or have given their competition law enforcement agencies, the equivalent of our Competition Bureau, additional competition advocacy powers.

International experience shows that there is no one “right” model for competition advocacy. Some countries place advocacy functions within the central government, others grant advocacy powers to the competition law enforcement agency, and a few have created an independent advocacy institution. Several countries distribute advocacy responsibilities across government institutions.

Taking the approach of using a specialized competition advocacy institution is likely to provide the best prospects for sustained improvements in Canada’s productivity. The increasing economic and legal complexity of competition law enforcement in Canada is a challenge for the Competition Bureau. Competition law enforcement is not restricted to the domestic arena; it has an increasingly complex international dimension, where enforcers coordinate investigations. Providing the agency with additional advocacy responsibilities risks diluting the Competition Bureau’s core enforcement effort.

The CPR Panel advocated the separation of enforcement from the advocacy and review function. The administration and enforcement of competition law should remain exclusively with the Competition Bureau. These two sides of competition policy demand different skills and orientation.

Independence is critical. A council that is free to speak out without being constrained by the bureaucratic or political ramifications of its work would be the most effective way to advance an agenda for a more competitive Canada.

Since all levels of government must engage in a national effort to make Canada more competitive, provincial and municipal representation should help to assure that competitiveness issues are addressed regardless of where they reside. As stated earlier, we believe that there needs to be greater recognition of the importance of urban centres to our economic prosperity.

The CPR Panel envisioned that such an organization would fill gaps in the competitive process in the country with activities such as:

- reviewing existing laws and regulations, regulatory agencies and processes that affect competitiveness, and issuing reports with actionable recommendations;

- reviewing private sector activity affecting competition, markets and productivity outside the realm of competition law enforcement, and issuing public reports with actionable recommendations addressing competition and productivity issues;

- reviewing progress toward the elimination of internal barriers to the free flow of goods, services, people and capital; and

- conducting research on any other issues that the Council deems to have a material impact on Canada’s competitiveness and publicizing the results and recommendations.

At the same time, independence and effectiveness could be undermined by government requests to study issues that are unrelated or immaterial to competition. The ability of the council to control its agenda and set its priorities will be essential to the council’s independence.

A foundational principle governing productivity is that competition drives innovation, which in turn drives productivity. It follows that when we have suboptimal competition we can expect suboptimal innovation and suboptimal productivity. We may decide for social reasons to reduce competition within a sector of our society, but we would be unwise to expect that the same sector perform at the same productivity level while ignoring the policy decision to relax competition. We can’t have it both ways. We either protect or we compete. Otherwise, we doom all actors to trying to achieve something that is likely impossible and worse, wasting precious resources and time in the pursuit of an objective that cannot be achieved. Better that we simply accept the sub-optimal performance and apply our energies elsewhere, lest the economy and society carry the cost of the double burden of trying to both protect and compete. Such is the situation facing Canada.

We have made policy decisions in previous generations that have shaped the modern Canadian economy, and these decisions have resulted in protected sectors of reduced competitive intensity that have led to reduced innovation and productivity.

Competitive intensity in a sector is a social debate as much as it is an economic one. But, we must not discuss the two separately. It would be hypocritical to have on the one hand an aspiration of control and sovereignty and in the next moment argue that this system should be just as innovative and productive as a global one that has more competitive pressures. We cannot have it both ways, and we cannot speak of one in isolation of the other. Therefore, productivity and innovation is actually a societal discussion for all Canadians as much as it is a debate for economists.

What makes the impact of this debate important for Canada is the timing. We are at the dislocation point between an old economic order and a new one that may last for decades, if not centuries. Innovation is the wealth creator in this new order, and we would be wise to structure our economy to optimize our ability to innovate and thus compete globally.

Photo: Shutterstock