Canada’s policy community has been consumed in recent weeks and months with analysis and commentary about the opportunities and potential hazards of a broad new security and trade partnership being negotiated between Canada and the United States. Many of the expected questions and comments have instantly arisen: Does Canada really have much of a say, when the US says it wants to build a tighter perimeter around the continent? Would Canadians’ privacy rights and sovereignty be protected? Is it reasonable in this age of integrated economies to have unintegrated security processes? Can Canada afford not to participate in a new arrangement, with our export dependency on the US market? Is this a golden and rare opportunity for Canada to be a net economic winner, when most of the rumblings south of the border have been about thickening the border and introducing “Buy American” policies?

These are important questions that are being evaluated extensively by the commentariat, and by trade, security and legal experts. It is important, however, to add additional elements to this discussion, and to take stock of some of the realities of Canada-US transborder movement often omitted from the usual debate. These developments concerning perimeter security also invite us to consider some of the wider opportunities and challenges of greater economic and security integration with the US.

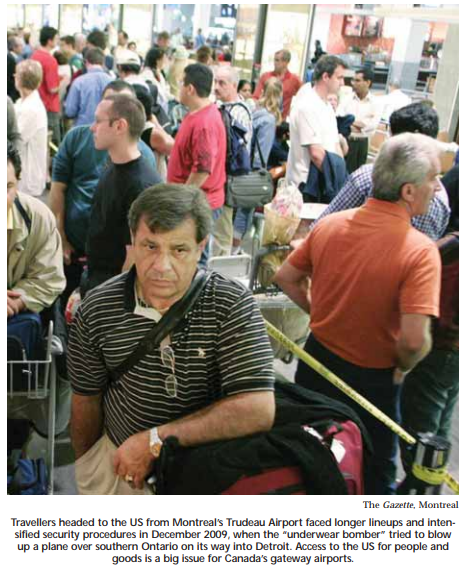

Much of the dialogue concerning greater Canada-US border integration has focused on the land border. Given the huge number of people and the vast amount of trade crossing the world’s longest undefended border each day, this is to be expected and deserves focus and attention. We are accustomed to the visuals of long queues at the major land crossings, and we have heard repeatedly of the economic impacts of cargo trucks delayed for hours, and the impact of these delays on just-in-time delivery. We have also all followed the saga of the Windsor-Detroit bridge and the impact of related policy decisions on the prospective movement of people and commercial cargo.

In order to have a fully rounded discussion of Canada-US border issues, however, it is critical that we evaluate the roles and opportunities of Canada’s real premier border crossings: our airports. The broad debate has largely centred on the complexities of facilitating the movement of people across the border, and the security challenges involved. Again, the mind instinctively goes to the land border. But in reality, nowhere else do we have such an intense concentration of trans-border human and cargo traffic and such an intensely concentrated security screening regime as we do at our international airports. Over the past half century, airports have displaced the land border as the chief portals of transit, and also as the principal nexus points of transit and security.

Connections between business, academic, scientific and cultural communities are made possible by the immediate access that air travel brings. Towns and cities that may be geographically distant are made neighbours. And every year, the proportion of people and goods that cross the border by air continues to increase.

Only by bringing this discussion to our airports as well as our land ports and crossings do we start to appreciate the full transit and trade picture, and begin to consider potential economic benefits of a better coordinated, more efficient border regime. Bilateral discussions that will lead to further border integration and cooperation between our countries can no doubt provide increased benefits in terms of convenience, security and trade. But increased integration with the US along the air border as well will enhance Canada’s economic competitiveness by contributing to the creation and growth of true “gateway” airports in Canada. The “gateway” airport concept presents an unparalleled opportunity to fully realize the economic opportunity of closer links between our two countries.

This discussion of greater integration, I would argue, gives rise to a conversation about the role of gateway airports as instruments of economic policy. In this discussion, we must reconsider traditional views of airports. Instead of seeing them as mere waystations on a family journey or a business trip, we have to come to a full realization that gateway airports play a vital stimulating role in economic development, while improving North American security and providing access for Canadians to the emerging economies of the world.

Connections between business, academic, scientific and cultural communities are made possible by the immediate access that air travel brings. Towns and cities that may be geographically distant are made neighbours. And every year, the proportion of people and goods that cross the border by air continues to increase.

A “gateway” airport is an airport that provides access to a large number of national, trans-border and international destinations. In addition to serving passengers and cargo from the city of origin, the gateway airport attracts connecting traffic from around the globe that uses this gateway as a connecting point to a myriad of destinations far and near. Gateway airports differ from regional or local airports not simply in the number of destinations served, but also in the number of passengers and cargo handled by the port. They are trade hubs, central to our country’s commercial infrastructure. Canada has three gateway airports: Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal.

The notion of airports on this scale typically calls to mind the vibrant economic enablers of Dubai, London Heathrow, Singapore, Hong Kong and Schiphol. Each of these facilities handles hundreds of thousands of people each and every day, thereby enhancing the economic and political power of their host cities and nations. They provide direct employment for thousands, but perhaps more importantly, the airports extend the cultural, business, academic and economic interests of their host nation around the world. One cannot speak of the importance of Singapore or London without also considering the role that their gateway airports play in realizing the economic powerhouse status of these cities.

Noticeably absent from any list of world gateway airports is a Canadian facility. While Canada is home to sizable modern facilities that are a credit to their municipalities, Canada cannot yet boast of a gateway airport that can compete with the leading airports in the world. As a result, Canada’s potential as an economic engine and Canada’s ability to grab a larger slice of the rapidly changing global economic marketplace are compromised.

To be clear, the development of gateway airports comes not simply from investments in steel and concrete. This has occurred, and continues to occur. What is needed is something more: an integrated policy that exploits the full economic value and potential of these ports of entry into and out of our economy. This policy approach will require various elements of government to work together with Canada’s largest airports to maximize the potential of true global access.

We argue that this policy framework should and must be focused on four essential aspects: security, passenger facilitation, sustainability and capacity. Security issues are critically important in that a safe conduit for the movement of people and goods is essential to dayto-day economic activity. Smarter and more effective security is necessary to reverse the “thickening of the border” that has become a common theme in Canada-US discourse in recent years. In a similar vein, smart capacity policy ensures the ability to accommodate future growth in the movement of people and goods: that is, in order to grow passenger and cargo traffic, you need room into which to grow the traffic. Passenger facilitation, in simple terms, is providing the best designs and procedures for guiding travellers through a port and taking full advantage of existing facilities to achieve maximum efficiency. Finally, sustainability concentrates on the environmental, social and financial impacts of air transport to ensure long-term growth, while ensuring that these national economic engines do not have a negative impact on local communities and the environment at large.

With respect to greater integration with the US, the aspects of security and passenger facilitation are particularly important, and will be explored further. First, however, we must explore the current landscape of Canada’s airports.

For a country all too often reticent to propose lofty international goals, it may seem somewhat audacious to suggest that a Canadian airport could ever compete on the global stage with the likes of Dubai, Singapore, Heathrow and Schiphol. Dismissing the potential of Canadian airports, however, ignores some crucial national and international developments that could, with the correct policy framework, thrust Canada’s airports, and therefore Canada, into the economic centre of global trade.

Starting in 1993, Ottawa transferred federally owned airports to local not-for-profit airport authorities mandated to manage, operate and develop their airports in a commercial manner in the economic interests of each region. The transfer of Canada’s airports to local authorities has allowed airports to access the capital markets to fund the drastically needed redevelopment of airport infrastructure in a way not possible under the constraints of government. Indeed, as a result of the investments made in Canada’s airports by airport authorities, Canada is well positioned to provide aviation access both now and into the future. This becomes crucially important as overcrowded and outdated US airports struggle to fund capital programs to meet the current capacity needs, let alone any future demand.

Canada is blessed with both the demographics and the geography to seize a large portion of the growing passenger volumes from Asia, Latin America and Europe. Canada’s diverse population means that we attract people from all corners of the globe to settle and to visit. This means that Canada already has a strong base from which to build traffic. Canada’s geographic location offers a unique opportunity for two reasons. The first is that we are a prime location offering shorter routes across the North Pole to Asia. As a result, flying times are shorter through Canada than through other locations. In addition, Canada’s close proximity to the US, when combined with efficient, modern and effective infrastructure, means that we can offer unparalleled access to the US for connecting passengers or cargo. Our major airports are strategically poised to be not only successful bilateral ports for passengers and cargo, but also efficient transit points for international commercial activity that both originates and ends outside of Canada’s borders.

Finally, Canada’s two main air carriers and Canadian airports’ most important partners, Air Canada and WestJet, are among world leaders in their respective classes. Both have won accolades in the industry and are achieving profitability and stability that are the envy of many. Each air carrier is poised for growth and sees the opportunities inherent in playing on the international stage, but what is most important is that both are well positioned to take advantage of any harmonized security regulations as they compete with US air carriers. This is of significant importance when considering the ability of Canada’s airports to achieve gateway status.

If we are to pursue greater integration with the US on border issues, and in turn, take advantage of this relationship to strengthen the development of gateway airports — and therefore trade pipelines for Canada — there are policy considerations that require the government’s focus. As we have identified, the required infrastructure is available, the location is ideal and we have the necessary strong domestic air carriers to achieve our goals. What further, then, is required from government policymakers?

Security: We cannot espouse the development of gateway airports without addressing the security issue head on. It is simply axiomatic that if we are to have sustainable and successful entry points into and out of our economy, then we must have an airport and aviation security system that not only appears to be effective, but is as effective as it possibly can be.

This calls for a reexamination of airport security. The federal government recognizes this, and has already taken steps to see certain changes to improve our system. But as these efforts progress, the discussion on the future of aviation security must not become mired in a discussion of who provides the security; rather, it should concentrate on how that security is provided. Is the security system pervasive throughout the airport? Is it fully proactive? Does it use all the available tools — human, methodological and technological — to achieve its ends? Does it allow and permit the sharing of intelligence across all security strata? Does it allow for the free and efficient flow of passengers so that additional security risks are not created?

Canada cannot yet boast of a gateway airport that can compete with the leading airports in the world. As a result, Canada’s potential as an economic engine and Canada’s ability to grab a larger slice of the rapidly changing global economic marketplace are compromised.

We urge greater cooperation with US security agencies and authorities. It is simply untenable for Canadians to deny the right or the need of the US to product itself against real and perceived threats. This alone should encourage us to work with our US colleagues to make sure that we complement their security apparatus, while ensuring that the threat to Canada is appropriately contained.

What is clear is that we cannot compromise security in favour of passenger service. We urge that the security question be viewed through the lens of what is necessary to grow the potential of the gateway airport to achieve the ends of economic growth. It is true that this demands stable, well planned and long-range funding, but we view this discussion as entirely appropriate given the potential return to Canadians.

Passenger facilitation: Passenger facilitation is simply the process by which passengers move through an airport to both enplane and deplane, or to connect between aircraft. While the issue is not complex when considering domestic flights, efficient and effective passenger facilitation becomes crucial in the building of a gateway airport. Successful gateway airports — the ones that grow into major economic engines for their local and national economies — are the ones that are able to meet minimum connecting times for passengers and are able to process more passengers, who, in turn, have a pleasant and hassle-free experience and then want to use the airport and mode of transportation again and again.

The need to enhance passenger connection is traditionally viewed as a hindrance to effective customs, immigration and health inspection services. There can be no doubt that Canada needs to be able to inspect, examine and interdict goods and people. Without this ability, Canada and North America as a whole are vulnerable.

Nations around the world have developed new ways to effectively inspect and process goods and passengers more quickly and more thoroughly while enhancing the passenger experience. Regrettably, too often in Canada we speak of customs and immigration from the perspective of whether the individual agent is polite or greets the passenger appropriately. It goes beyond that. We need to focus higher and in a more sophisticated manner.

Do we have the man-power necessary to inspect the current numbers of passengers, let alone the traffic that will result from the growing demand for international travel? Must we rely upon old inspection methods of having the passenger present to a customs official behind a desk? Must all passengers be inspected the same way, even when they are merely in transit? More importantly, how can we make use of technology, especially mobile devices and smart phones, both to enhance the ability of our inspection agencies to inform the passenger, and also to augment the ability to inspect and interdict? We must make better use of technology, such as the established trusted-traveller program Nexus and emerging programs such as Automated Border Clearance (ABC), which, as the name suggests, uses automation through kiosk technology to process lower-risk passengers.

From the vantage point of the Greater Toronto Airports Authority, we applaud the efforts of our government partners, and in particular the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) in their willingness to work with the airline industry to achieve excellence both in passenger service and in inspection. We do not advocate the erosion of one imperative at the expense of the other. Indeed, we ask for a concerted industry-wide effort to raise the bar in both areas.

A serious challenge, however, remains in clearing passengers to the US. At the core of a successful gateway strategy lies the pre-clearance program.

The magic of preclearance — a regime that has been in place for more than 50 years — is that a Canadian air passenger is introduced into a US airport as a domestic passenger, having already cleared US customs and immigration on Canadian soil. This is important for several reasons. First, with American inspection services concentrated, at the point of departure, dozens of destinations in the US that cannot support full stateside inspection services are now accessible by Canadian-originating passengers and those who travel from abroad but connect through Canadian airports. Over one million passengers annually travel through Toronto Pearson to US airports that do not have US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) facilities. Not only does this open up destinations in the US, but it also alleviates congestion faced at larger US airports that are also experiencing staffing resource pressures. Simply put, preclearance crucially improves two way trade, and it does so in a cost-effective manner. No other US-bound travellers, from anywhere in the world, receive the preferential treatment enjoyed by Canadians.

Preclearance has led to an exponential growth in traffic to and from all parts of the US; however, the success of this system is often not recognized. Pearson International boasts the largest CBP facility operated by the US government, processing approximately 4.5 million passengers each year; it consistently ranks in the top four to seven entry points into the US via air transportation.

Preclearance, in fact, is a prime case study of what can be accomplished in the broader “security perimeter” vision. It is a half-century old innovation that, if introduced today, would undoubtedly garner allegations of sovereignty compromise: US customs officials operating on our sacred soil! But it works. It works very well. It has worked for a very long time. And it works without any negative trade-offs. Preclearance is an established innovative program that has been in place for a half century and has made our gateway airports immeasurably more efficient in moving people and cargo between our two economies. As the Canadian and US governments engage in the “Beyond the Border” negotiations, they should study closer cooperation to thoroughly consider this program’s successes and emulate its effectiveness elsewhere.

Staffing levels and budgetary constraints in the US may indeed now be putting this invaluable service in peril, artificially constraining traffic growth and potentially reducing access for businesses and leisure travellers alike. Moreover, the resource crunch being experienced by our American neighbours cannot be wished away. We therefore need to work in cooperation with agencies, industry and business on both sides of the border to find innovative solutions that meet the demands for traffic to the benefit of the economy while achieving the primary objectives of CBSA and US CBP: protecting the integrity of our borders. The desire to harmonize regulation between our countries and the massive economic shift that is occurring now have rightly prompted discussions about increased integration with the US on perimeter security. Surely this discussion is fraught with concerns surrounding sovereignty, privacy and countless other bugaboo topics. Nevertheless, it is without question the right discussion to be having.

As the wider discussion on perimeter security progresses, it is prudent to consider the ancillary policies regarding security and passenger facilitation that can provide the necessary industry conditions that will create and sustain gateway airports in Canada. This is the next logical step in the policy debate. A discussion about cross-border policy cannot exclude the largest flow points between our two economies: our airports.

Does this policy pursuit mean that government, in a policy context, will have to treat Toronto and Vancouver differently than Moncton and Winnipeg in order to ensure that Canadian airports can compete not only with US hub airports, but with other global gateways, like Dubai and Singapore? Does it mean that there will be initiatives that are found in Montreal and Toronto that may not be found in Thunder Bay or St. John’s? Yes. This reflects the reality of our trade and transit circumstances, and will allow our airports to realize the potential for a proper gateway system in Canada.

Only a mature, thoughtful and integrated policy approach that moves fully beyond treating airports as utilities and sees them as the complex and sophisticated conduits of trade and traffic that the security perimeter talks are addressing will fully harness the economic impact of our nation’s largest points of access. This means changing the way we think about airports, taking bold steps to improve and integrate security in smart and effective ways and not losing sight of the fact that the economy wins when this is done in a manner that addresses mutual security needs while maintaining high levels of user ease and satisfaction with the process of travel.

Photo: Shutterstock