As well as committing $19 billion to the second round of stimulus spending, the 2010/11 federal budget outlines a plan to gradually reduce the deficit from $49.2 billion in 2010/11 to $1.8 billion in 2014/15 (and presumably to zero in 2015/16). Cost-cutting measures include ending stimulus spending as planned (except for work-sharing agreements); a three-year freeze of departmental budgets and the salaries of the prime minister, ministers, members of Parliament and senators; restraining government administrative costs and reviewing programs; freezing international assistance as of 2011/12; and reducing the rate of growth of military spending as of 2012/13. Also, tax loopholes will be closed and employment insurance premiums, which are currently frozen, will increase after 2010.

There is a compelling case for the need to balance the budget over the medium term. By 2014/15 more than $158 billion will have been added to the debt since 2008/09, and Canada’s debt will be over $622 billion. Also, an aging population will pose long-term economic and fiscal challenges, and Canada needs to get its fiscal house in order to address these.

The debate centres on how quickly the budget should be balanced and the best policy choices for achieving balance. Budget 2010/11 charts a moderate course: budget balance will be achieved gradually over six years, cost-cutting measures do not affect taxpayers directly, and if the modest measures outlined in this plan do not produce a balanced budget, then there is time and a commitment from the Minister of Finance to take further action. Some critics have argued in favour of an approach more similar to that of the 1990s: the budget should be balanced more quickly, and a more detailed deficit reduction plan with bolder cuts is required. Also, some have advised the federal government to raise taxes; for example, the GST could be raised to 7 percent. Is this a wise policy choice? Answering questions like this involves examining the medium-term deficit reduction strategy, as well as the long-term fiscal decisions needed to deal with Canada’s ongoing challenges like an aging population.

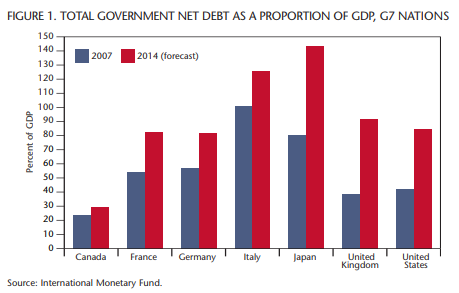

Despite the deficit and the challenges of an aging population, the strengths that we have today, relative to the 1990s, are considerable. Our fiscal situation is the envy of the Western world (figure 1). Our debt-to-GDP ratio will peak at about 35 percent, while that of the US is 67 percent. In contrast, in the 1990s Canada faced a fiscal crisis: in 1995 an editorial in the Wall Street Journal was entitled “Bankrupt Canada?” Facing such an obvious and dire crisis, governments in the 1990s implemented bold and politically difficult measures with the support of the public, which is absolutely essential to the success of drastic budget cuts or tax increases. But how can governments today persuade Canadians that dramatic cuts or tax increases are essential when our underlying and comparative financial situation is so strong and we are just beginning to recover from the deepest recession since the 1930s? Without significant public support for bold deficit-cutting action, even a majority government would find it difficult to sell a budget that spends $19 billion to ensure that the economy continues to recover at the same time as it introduces significant program cuts or tax increases to end deficit spending.

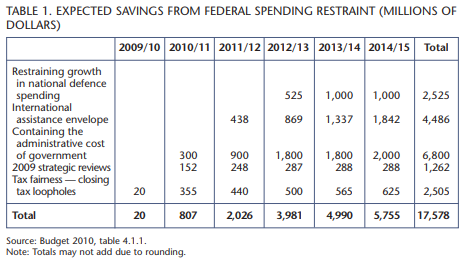

Also, the absence of a 1990s-style fiscal crisis means that governments have the time and the opportunities to make good policy decisions for the medium and long terms. One opportunity is to review government spending, which has increased significantly in the last decade; in the last five years alone government spending has grown about 6 percent per year. Thus, reviewing programs to determine if they are still relevant or necessary, scrutinizing administrative costs and asking whether all retiring federal public servants need to be replaced are valuable exercises, and table 1 shows expected five-year savings of $17.6 billion. However, caution is necessary to ensure that the image of the federal government as an employer is not fundamentally tarnished by such measures, since the retirement of the baby boomers will require the recruitment of talented young people to fill their places. Moreover, freezing budgets across the board is a blunt instrument and will prove difficult when salary increases of 1.5 percent have to be absorbed. Nonetheless, there is a good case to be made for beginning by trimming government spending before resorting to more drastic cuts or tax increases.

There is a compelling case for the need to balance the budget over the medium term. By 2014/15 more than $158 billion will have been added to the debt since 2008/09, and Canada’s debt will be over $622 billion. Also, an aging population will pose long-term economic and fiscal challenges, and Canada needs to get its fiscal house in order to address these.

Another advantage today’s budget cutters have is that there is “tax room.” In the 1990s a tax wall had been reached: 43 taxes were increased between 1984 and 1993. In contrast, taxes have been reduced in the last decade, so that, for example, by 2012 Canada will have the lowest corporate tax rate in the G7. There is “room” for Canadian taxes to increase without affecting our competitiveness, but is the best long-term policy choice to raise the GST back to 7 percent? Answering this question requires a brief discussion of the longer-term policies required to deal with the economic and fiscal costs of an aging population.

For years governments have emphasized increasing Canada’s productivity to help address the labour shortages that will result from the retirement of the baby boomers, and some measures in Budget 2010/11 address this issue. Research and development received the lion’s share of new spending, although there is limited money available for new environmental initiatives. There is $40 million over two years to support innovation by small and medium-sized businesses, which is important, since businesses of this size lag behind those in other countries in innovation. The commitment to make Canada a tariff-free zone for industrial manufacturers by eliminating all tariffs on machinery and equipment and goods imported for further manufacturing will also encourage businesses of all sizes to innovate and enhance their productivity. The stimulus package’s focus on infrastructure spending is helping reduce Canada’s infrastructure deficit, although only a fraction of the money is going into “new” infrastructure like information technology. And the continuation of corporate tax cuts has made Canada’s tax regime very competitive. Other policies to address labour shortages include streamlining Canada’s immigration system and encouraging older workers to remain in the workplace longer.

The other key issue raised by population aging is finding the money to pay for programs whose costs will progressively increase. These include seniors’ benefits and especially health care. The issue that keeps finance ministers awake at night is the relentless increase in health care costs, which are growing at a faster rate than the revenue growth of any government and squeezing out funding for other services such as social programs or education, which are important determinants of good health. Though restructuring and cost-savings might help, addressing the spiralling costs of health care will require finding a new revenue stream to pay for the services. How should new revenue to fund health care be raised, and by what level of government? Answering these questions requires a discussion of the transfers that the federal government pays to the provinces.

The federal government is committed to increasing its transfers to the provinces by 6 percent per year for health care and 3 percent for social programs until 2013/14, and when these agreements expire there will be pressure for continued or even more federal funding to reflect rising costs. But would this be a good policy choice? In effect, the federal government would have to raise taxes (for instance, the GST) and turn a substantial portion of the new money over to the provinces — which design and administer health, education and social programs — with no power to influence how that money is spent. Accountability would be compromised: one level of government would be raising taxes for programs that are delivered by another level of government.

A much better approach after 2013/14 would be for the federal government to restrict its transfer payments to the provinces, by limiting their increase to the rate of growth in federal revenues, and in exchange commit to not raising federal taxes, leaving the tax room to be occupied by the provinces. Thus, the provinces, which design and administer health care and other social programs, would also have the capacity to increases taxes to pay for them. The result would be more effective accountability and a better link between the costs of health care and the revenues required to pay for it.

A second issue is what new revenue measures should be adopted to fund health care costs. Raising traditional taxes like the sales tax would mean that a significant part of the burden of health care costs would be borne by younger taxpayers in the workforce. But in an era of labour shortages and a global economy, will younger taxpayers accept higher and higher taxes to pay for programs used to a greater extent by seniors, or will they be attracted to other jurisdictions with more competitive tax rates? Instead, provincial governments should consider the proposal of Tom Kent, who was policy adviser to Prime Minister Lester Pearson when medicare was introduced. Kent advocated making health care a taxable benefit. With this approach people would pay part of the costs of health care, based on their ability to pay, and as health care costs increased, so would the revenue stream to pay for them. Moreover, as the baby boomers age and their use of their health care system increases, so too would their contribution, relative to their income, to the funding of it.

Thus, addressing Canada’s deficit will require both a medium-term strategy to reduce spending and a longer-term policy discussion about how best to deal with challenges like our aging population. In this sense, Budget 2010/11 is a transitional document. It makes the case for reducing the deficit over time and presents some initial ideas about how that might be achieved. But other major decisions are left for the future.

Whether the measures outlined in this budget will achieve a balanced budget by 2015/16 is an open question. Aside from ending the one-time stimulus money, the cuts in the budget plan produce only $5.7 billion in ongoing savings by 2014/15, which means that balancing the budget will depend heavily on revenue increases from a growing economy and very tight fiscal management. Considering past spending increases, limiting direct program spending to only 1.3 percent per year from 2013/14 to 2014/15 (as the budget proposes) will require extraordinary focus, commitment and discipline. Regarding the revenue projections in the budget, some analysts say that they are too optimistic and the revenue to balance the budget will not materialize; others, like the Conference Board of Canada, contend that they are too conservative and the budget can be balanced ahead of schedule. What is critical is that a framework has been established for future debates. The government has proposed a moderate, modest plan to progressively reduce the deficit over the medium term. Meeting these targets and progressively reducing the deficit will be essential to the government’s credibility as fiscal managers. But the budget should also pose questions for the opposition. Do the opposition parties agree with this moderate approach to deficit reduction? If they do not like this plan, what is their alternative? If a party proposes major new tax cuts, then it should tell us what programs will be cut. If a party promises to introduce major new spending initiatives, then taxpayers need to know what taxes will be increased. If the effect of Budget 2010/11 is to frame the fiscal debates of the future in these terms, it will have achieved its main purpose.

Photo: Shutterstock