“The immediate emergency phase may be over, but the long-term work is just beginning, and it’s no less an emergency,” warned Karline Kleijer, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) head of mission, a mere seven weeks after the January 12 earthquake. The future remains uncertain for essential health care in the affected region of Haiti.

Before the catastrophe, more than half of the Haitian population could not afford health care. More than 70 percent of them were reported to be living on less than US$2 per day. The capital, Port-au-Prince, a city of 3.5 million people, with many living in slums, had 21 public health facilities and only four hospitals. These fee-for-service facilities lacked medical staff, equipment and supplies. Haiti’s health care system before the earthquake was insufficient to address the basic medical needs of the population in Port-au-Prince. Now, in the aftermath of the earthquake, the level of medical need has increased dramatically.

As we write this Policy Options article, more than two months after the cataclysm, many of the smaller medical organizations have left or are leaving. MSF sees a limited, and certainly inadequate, response to providing basic shelter to the displaced. Reflecting back on the aftermath of previous natural disasters in Haiti leaves us far less convinced than others who see the outpouring of global compassion for earthquake victims as an indicator that everything will turn out for the better in the end.

Will there be sufficient medical capacity to deal with the large numbers of patients requiring postoperative care, specifically rehabilitative and psychological care, over a longer period? How many Haitians will suffer from living in inhumane, undignified living conditions in overcrowded and violent camps without access to adequate shelter and sanitation? Will many of Haiti’s displaced experience a second traumatic displacement when the hurricane season slams them in June? Will there be enough medical capacity, after six months to one year, to deal with the normal levels of medical emergencies experienced by cities of this size?

MSF medical teams already in Haiti on the night of the earthquake faced extreme conditions: severe injuries, small fires burning, corpses on the streets, frantic crowds searching desperately for buried loved ones and widespread levels of physical devastation. The wounded poured into MSF’s makeshift hospitals on the streets. Our staff struggled to treat the influx, while at the same time trying to locate their own colleagues and families, many trapped in rubble.

The first phase of the medical response with mass casualties lasted about 10 to 14 days. Several MSF hospitals were severely damaged. Survivors pulled patients and other staff — both dead and wounded — from the rubble. La Trinité trauma centre collapsed with patients and staff inside, including our most senior surgeon, Erick Edouard, who was one of the seven MSF employees killed in the quake. The Maternité Solidarité emergency obstetrics hospital managed by MSF Canada was rapidly evacuated as it was on the brink of collapse. Babies don’t stop being born when disaster hits, and more than a few were delivered outside that night amid the chaos.

In the meantime, MSF teams rapidly set up emergency first aid posts and focused on stabilizing the hundreds of wounded who sought our care. They rigged makeshift lighting with generators, cars and flashlights. In four corners of the street in front of the collapsed hospital, team members worked 24 hours straight until patients filled every available space on the ground.

Patients arrived with multiple and open fractures, crushed limbs, deformed faces, skull fractures, spinal cord injuries and life-threatening burns. Teams concentrated on wound cleaning, debridement and dressing, and fracture stabilization. Infection of untreated wounds set in quickly since the entire population was living outside. Within the first week medical teams encountered gangrenous wounds, hemorrhagic shock and septicemia, as well as a type of renal failure known as crush syndrome.

In Haiti, an estimated 300,000 people were wounded at once. This called for a drastic approach to triage, with priority given to persons who could survive with the smallest amount of resources possible. Most of the international doctors and nurses responding to the quake, including MSF staff, were accustomed to triage that prioritized persons with lifethreatening injuries that could take up a lot of resources. Sometimes switching gears was difficult.

Logistical teams searched damaged MSF hospitals for equipment, material and drugs. Contingency stocks were kept specifically for emergency preparedness scenarios, allowing MSF to rapidly start working. However, we never envisioned a disaster of this scale; materials were quickly used up in the first weeks of response.

We expended significant effort to secure direct landing access for essential medical and nonmedical supplies in Port-au-Prince. However, flights with supplies and disaster experts were diverted to the Dominican Republic because the small airport in the Haitian capital was damaged and overloaded with flights competing to land, and the air traffic priorities remained unclear.

MSF medical teams already in Haiti on the night of the earthquake faced extreme conditions: severe injuries, small fires burning, corpses on the streets, frantic crowds searching desperately for buried loved ones and widespread levels of physical devastation. The wounded poured into MSF’s makeshift hospitals on the streets. Our staff struggled to treat the influx, while at the same time trying to locate their own colleagues and families, many trapped in rubble.

We desperately needed dialysis machines to save the lives of the many patients suffering from crush syndrome. It was unspeakably frustrating for medical teams to watch patients die for the lack of dialysis — the machines were en route to Port-au-Prince, only to be diverted from landing. There is no doubt that problems at the main airport resulted in severe delays in the provision of urgently needed life-saving assistance. In the end, most MSF supplies were routed through the Dominican Republic, where MSF established a supply base in Santo Domingo. Even if this is a longer route, it provided a more stable and reliable option for the initial months, as the airport and the seaport, even if open, remained overburdened.

By the end of the first week, MSF estimated we had treated more than 3,000 wounded people in the Haitian capital and performed more than 400 surgeries (of these, about 10 percent were amputations).

This natural disaster in Port-au-Prince differed from others in two significant ways. First, it directly affected the urban capital infrastructure, and consequently the capacities of all governmental, United Nations, non-governmental and private agencies to respond. Second, because it hit densely populated areas of poorly planned and unregulated settlements within the capital, the scale of immediate medical need among those injured was massive. This exceeded the caseload managed during the 2004 tsunami or in the Pakistan earthquake of 2005. This combination meant a huge need on the one hand and severe challenges to the response on the other.

The medium-term response in Haiti leads to several important questions. Emergency and postoperative Care. Will sufficient medical capacity remain in the country to provide quality postoperative care? As more and more medical organizations are leaving, the answer is unclear. In Port-au-Prince there is a virtual marketplace for the recycling of patients to other health care providers. In the last week of February alone, MSF received 200 patients from medical groups pulling out of the country.

“Emergency surgery is one thing, but lack of, or inefficient, postoperative care will result in long-term hospitalization or even in life-long physical disabilities,” explained Nico Heijenberg, an MSF physician working in Haiti.

With so many injured, patients who are living in unsanitary and rudimentary conditions, postoperative complications such as wound infections are to be expected. Likewise, with so many severe traumas, spinal injuries and amputated limbs, the need for longterm medical rehabilitation is high.

Added to the burden of postoperative care are the daily medical emergencies experienced within any city the size of Port-au-Prince, Carrefour and Léogâne. What capacity will exist to treat the daily influx of car and motorcycle accidents, people injured trying to recover their property from destroyed buildings, burn victims resulting from tents catching fire with paraffin stoves, violence-related trauma such as gunshot wounds and stabbings, and other emergencies such as complications during pregnancy? In October 2009 alone MSF admitted 1,470 patients into its emergency obstetrics hospital. Access to general hospital care will be the next emergency. How many people will die because of an inadequate capacity to deal with daily medical emergencies?

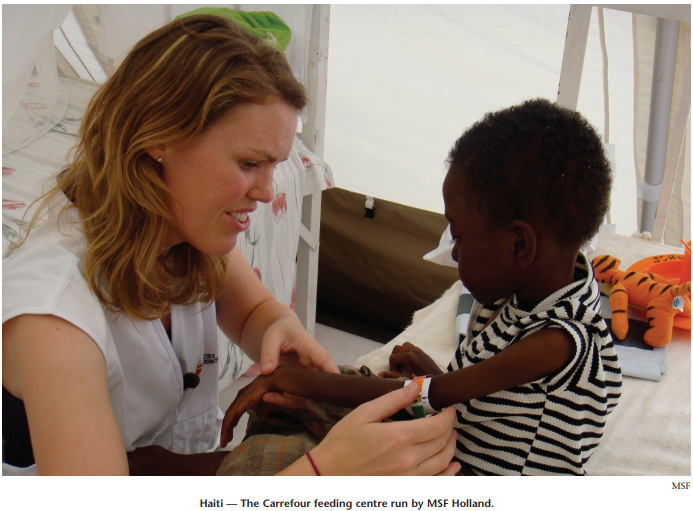

MSF is currently managing one of the few in-patient therapeutic feeding centres targeting moderately and acutely malnourished children. These are increasingly being referred from other organizations working in camp settings. In the matter of a few weeks 60 children were admitted into care.

Exposure to wind and rain. For how long will the unhealthy and precarious living conditions of the Haitian homeless and displaced continue? The UN estimates approximately 200,000 are living in 300 resettlement sites throughout the affected region. The living conditions of many of the displaced are shameful. Many of the settlement sites are simply not large enough to accommodate tents and shelters for so many. People express fear of living in these camps. We hear numerous stories of robberies inside the camps, intimidation and extortion on the few jobs available and — even if not yet recorded in high numbers — a lot of reference to rape taking place.

Almost all of the settlements rely on drinking water being trucked in and treated on site. The majority of sites have insufficient water or space for bathing privately, putting children and women at risk of exposure to harassment and abuse. A huge need is the absence of latrines, leading to shameful and undignified living conditions. Most camps have far in excess of 100 persons per latrine.

Environmental health conditions in camp settings are generally poor. Water and sanitation are often at or below minimum thresholds, and families are densely crowded in temporary shelters. In these conditions, diarrheal, respiratory, vector-borne and other diseases flourish. Further exacerbating the situation, people are often weakened by illness, exposure to the elements and poor nutrition, making them less able to fight off infection. Even before the earthquake, diseases such as dengue, malaria, typhoid fever and others were highly endemic. In a weakened population, there is not only an increased likelihood of infectious disease, but also an increase in mortality.

Given the health risks, the priority should be to quickly identify alternatives to the precarious camp shelters, particularly as the onset of rains will likely make these temporary settlements even more untenable.

Solving this problem is far from easy. Organizations involved in providing shelter are torn between creating large planned settlements, encouraging people to build temporary housing within the cities, and moving people to rural areas to move in with host families who are also strained by limited incomes.

The chosen strategy was to discourage large planned settlements. The response for shelter is split into three phases first, provide emergency shelter such as tents and plastic sheeting; second, provide resources for temporary shelter that will withstand the heavy rains and winds expected to begin the first of May; finally, rebuild.

More than two months on, many people still lack even basic shelter and are living in crowded, unsanitary camps spread throughout the cites. Even phase one has been desperately slow. Now two large settlements are being planned, with the incentive of assistance to make people move there.

It will probably be precipitation that changes the current status of the displaced camps. As the rainy season starts, many of these sites will be washed away or become impossible to live in. This will sadly be the impetus that drives those who still have homes — damaged or not — or access to extended family to overcome their earthquake fears and return to living indoors. The remainder will likely go through another phase of resettlement, either to prepared camps or to those locations that are not as severely affected by the rains.

June marks the official start to this year’s hurricane season, when even the best tented structures may prove inadequate and unsafe.

While it is impossible to play the prophet, insights from the past can illuminate the future. If this is the case, MSF does not share Bill Clinton’s optimism that the earthquake was an opportunity “to build [Haiti] a functioning, modern state for the first time.”

In 2008 Haiti was struck by two tropical storms and two hurricanes in succession. Five weeks after the hurricane, 10,000 out of a total population of 200,000 were still living on roofs, in tents or in fragile shacks made of scrap wood and bed sheets. Instead of reducing our medical operations, as is usually the case in this type of natural disaster, MSF was forced to scale up. In the city of Gonaïves, MSF started a temporary hospital in a new site to replace the city hospital buried in mud. Nine months later, when MSF handed what was intended to be a temporary structure over to the local health authorities, the city hospital was still full of mud, despite the huge outpouring of financial assistance and media attention the hurricanes had generated.

Increased vulnerability, decreased health care? What capacity is there to maintain a reasonable access to basic health services for these vulnerable populations? It is through out patient services that most complications can be identified, treated or referred before they become life threatening. Prior to the earthquake, these public services were available only for a fee, and were not targeted at those in greatest need anyway.

International donors have long been reluctant to invest in government-managed programs in Haiti for fear of poor accountability, mismanagement and corruption. The country has also suffered years of brain drain of its experienced and qualified human resources, as many have sought to emigrate and join the diaspora in Canada and the US.

While we all hope that the Haitian Ministry of Health (MoH) will quickly get back on its feet, its capacity was insufficient to meet the preearthquake medical needs of the population. With so many hospitals destroyed, the migration of homeless MoH medical staff and the lack of infrastructure, how much can we expect the MoH to recover? Will the combined capacity of the MoH and the remaining medical organizations be sufficient to cover even the basic, life-saving needs of the earthquake-affected population? The shared operations of MSF in Port-au-Prince in recent years have cost in the region of C$20.5 million a year. This equalled two-thirds of the entire Ministry of Health budget for Haiti.

International donors have long been reluctant to invest in government-managed programs in Haiti for fear of poor accountability, mismanagement and corruption. The country has also suffered years of brain drain of its experienced and qualified human resources, as many have sought to emigrate and join the diaspora in Canada and the US.

As a result most of the aid money going into the Haitian health sector has been channelled through implementing partners such as NGOs and others working in the private sector. This leaves the Ministry of Health little option but to implement user-feebased services for patients and cost recovery systems for medicine, thereby excluding those who can least afford to pay.

Public hospitals have historically been plagued with strikes, and have struggled with issues of internal corruption as health care workers feel forced to find ways to compensate for their lack of regular income. The health care agenda was largely overlooked at the last international donor conference in 2009, which ignored MSF appeals that it be given priority.

In Washington, in the weeks prior to the installation of the Obama administration, the dominant view of health care funding for Haiti was disappointing. “Why would the USA prioritize the access to health care of 7 million Haitians when we have up to 40 million Americans in a similar situation?” a Capitol Hill official challenged.

If there is going to be a sustained commitment to Haitians following this tragic disaster, it will be essential to have a commitment to the funding of public health services, the development of a health plan tailored to the needs of Haiti’s impoverished population, incentives to encourage the return of health and other professionals and strong coordination in the health sector. MSF will continue to lobby the government and donor countries at every opportunity to promote these propositions.

There have been unprecedented financial commitments made to Haiti following the earthquake, something in and of itself that will motivate donor-dependent organizations to develop programs in order to simply spend the money. Likewise, many organizations have received massive sums of private income, MSF included. To cast a critical eye inwards, MSF was on the point of scaling down operations in Port-au-Prince before the earthquake to two operational sections, aiming for greater efficiency and a rational approach to needs in Haiti compared to other contexts around the world, and also to rebalance our global priorities for medical humanitarian assistance.

After the earthquake MSF now has five operational sections in Haiti, with a combined planned budget of more than C$68.4 million for 2010 alone. NGOs, including ourselves, need to think critically about how to rationalize efforts to meet the plentiful needs in Haiti in a way that aims to limit, as far as possible, duplication of services and competition for activities or “intervention space,” and be accountable for the responsibility increased financial independence offers. Not as easy or as obvious as it sounds.

The health and well-being of Haitians is clearly at great risk in the short, medium and long terms. It is unclear what capacity for the provision of emergency and general health services will remain in the country over the coming months. It is equally unclear how quickly the Ministry of Health can resume responsibility given the severe impact on infrastructure, financing and staffing this earthquake has had. Immediate needs are already apparent, and these are no longer only linked to the emergency care that resulted from the earthquake itself. As time goes on, health care providers are adapting their programs to meet the general health needs of the population. Many are not prepared or committed to do this, and will leave or have already left.

The crisis of homelessness and displacement remains unresolved. Temporary camps are precarious, and increasingly threatened by the onset of rains. Living conditions are poor and will, over time, contribute to an increase in preventable disease.

Access to health services for poor Haitians in Port-au-Prince was already inadequate before the earthquake, with very few free or sufficiently subsidized health programs to provide essential care to a population where the majority live below poverty thresholds in precarious settlements. Re-building the former level of services is therefore clearly not enough, and re-introducing user-fee-based health services or costrecovery programs for a population that is now even more vulnerable will deny those with the greatest need access to essential life-saving care.

Unless international donors and key stakeholders place sufficient priority on proper and accessible health care in Haiti, the future, both short and medium term, looks bleak. As evidenced in the past, the international community has failed to maintain a sustained commitment by investing in public health services and not just the private sector, embracing the need for free or subsidized health services and supporting the development of a long-term health plan. Without this the vast majority of health programs will continue to be run in parallel to those of the MoH, with little effective coordination, and with models aimed at restoring the past services instead of models aimed at reaching those in greatest need, with the highest health risks.

Photo: Shutterstock