Precarious: dependent on chance circumstances, unknown conditions, or uncertain developments; characterized by a lack of security or stability that threatens with danger. (Merriam-Webster)

Precarious has become a favoured term for describing how many people feel about the labour market lately. I will clearly state that I think living ”œprecariously” is an important policy concern. I simply take issue with the folks who want us to believe this is a new issue or that this type of employment has taken over the lives of growing portions of the population. The labour market has clearly changed over the past several decades, and the population participating in the labour market has changed at the same time. To say, however, that we now live more precariously than before requires (in my very humble view) some bit of evidence.

In determining whether jobs have become more precarious, I’d first seek out data describing people’s ability to keep their jobs – that would represent the uncertainty that workers face. The best evidence we have for job stability trends comes from Pierre Brochu (University of Ottawa), who measures job retention rates up to 2010 (see his Canadian Journal of Economics publication here). One-year retention rates were remarkably stable since the 1990s; the retention rates for new employees (with less than one year tenure) increased over time and reached a historical high in 2007. I’ve encouraged Pierre to update the analysis (nudge), but it’s doubtful the labour market has shifted dramatically since 2010. In short, the job stability data is not going to suggest an increase in ”œprecarious” work.

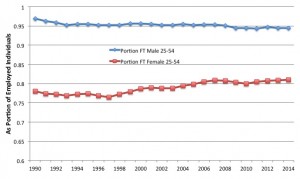

Perhaps then, we can have jobs that are precarious because they lack predictable schedules. As a job quality measure, many turn to the portion of jobs that have part-time schedules. I used data from Statistics Canada (CANSIM 282-0004) in the chart below, which shows an increasing portion of women’s jobs (among prime-age workers) has been full time, while there is a slight decrease since 1990s in the portion of working men that have full-time jobs. So, perhaps the quality of jobs for men has declined slightly by this measure.

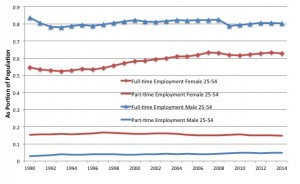

The composition of the labour force (who seeks out and has jobs) has changed over time, however, so I prefer to think about how the population’s activities have changed over time rather than conditioning on employment. For that, I plot the portion of the population aged 25-54 that holds full time and part-time employment, similar to how we would measure an employment rate.

Here is an interesting story that gets too little attention. For women, the likelihood of working full time has increased substantially over time while the chances of working part-time has not changed much and actually declined over the 2000s. For men, the chances of working full time in the past few years are lower than the early 2000s, but remain above full-time rates for the early 1990s. The chances of working part-time for men have increased.

In short, we might make the case for things becoming increasingly difficult for men in the labour market, but certainly not for women.

But why would we assume the part time jobs are necessarily lower quality and precarious – I know many people (male and female) who actively seek out part-time and flexible work schedules to help them balance work and family. This is viewed as a good thing!

I took a closer look at the 2014 Labour Force Survey data, in which they ask individuals working part-time why they do so. Among those 25-54, 20% of men and 23% of women working part-time simply prefer to do so. Among the women working part-time 25% do so because they also care for children.

Certainly, 21% of men and 11% of women aged 25-54 who were working part time said it was due to business conditions and they had looked for full time work. An additional 29% of men and 23% of women had said it was due to business conditions but they hadn’t actually looked for full-time work. This is the group that I might think of as a policy concern. So, a group representing about 2% of the male prime-age population and about 5% of the female prime-age population may represent a policy concern with regards to the quality of their employment.

Is that part-time work precarious? It may be perfectly stable and secure, just not preferred. That in and of itself is something that policy makers should pay attention to – there is a group willing and able to work more and they appear to be underutilized. This requires more data.

But please, let’s stop talking about work becoming more precarious without also offering some clear measure and definition for what this means. Pleas to implement new policy based on one’s gut feeling are driving me crazy.