A useful report by IRPP researchers Antoine Bilodeau, Luc Turgeon, Stephen E. White and Ailsa Henderson on the views regarding the federation of visible minorities, divided into both immigrants and second or more generations.

A useful report by IRPP researchers Antoine Bilodeau, Luc Turgeon, Stephen E. White and Ailsa Henderson on the views regarding the federation of visible minorities, divided into both immigrants and second or more generations.

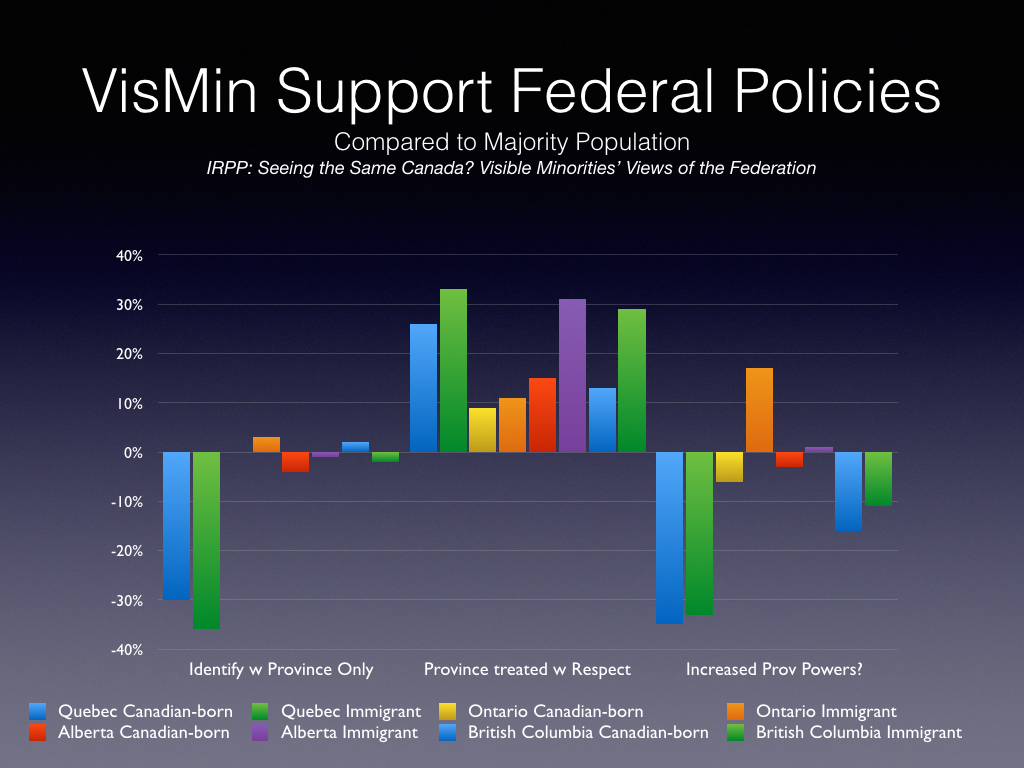

These regional differences, while not terribly surprising, nevertheless are revealing in that they reflect the overall regional perspectives (similarity between visible minority and majority population in Ontario, weaker regional grievances in the West among visible minorities, and greater support for national institutions in Quebec among visible minorities).

While the authors observation that the federal model of multiculturalism is attractive to visible minorities is not new, it highlights the failure of Quebec’s efforts to create an alternative interculturalism narrative, along with the all too often exaggeration of the nuanced differences between the Quebec and federal approaches.

As to their recommendation that the Quebec government should adopt a formal interculturalism policy, while sensible in some respects, this would likely reopen some of the less productive debates of the past (e.g., the PQs late unlamented Quebec Values Charter). Ironically, it also might undermine the rhetoric of the Quebec model of interculturalism, given that any articulation would likely only highlight how subtle the differences are with multiculturalism.

One of the weaknesses of CIC/IRC citizenship program was precisely its lack of stronger citizenship promotion in Quebec, which reflected more processing and efficiency concerns rather than reinforcing Canadian identity. This will likely continue, even if it is one of the few IRC programs in Quebec, given that most immigration and settlement programming was transferred to Quebec under the 1978 Cullen-Couture agreement, one that can play an important role in reinforcing the federal presence in Quebec.

The transfer of multiculturalism back to Canadian Heritage will provide scope for more multiculturalism programming in Quebec and thus reinforcement of Canadian identity. (Within CIC, there was a feeling that under the Cullen-Couture agreement, which transferred immigrant selection and settlement services to Quebec, that multiculturalism program funding for Quebec was not needed – missing an opportunity to assert federal presence.)

Executive summary of report:

The authors show that, compared with the majority population, members of visible minority groups as a whole have a stronger sense of loyalty to the federal government than to provincial governments, express greater support for Canada’s national policies, and are less inclined to endorse historical grievances about the Canadian federation. As for competing national and provincial visions of Canada, members of visible minority groups embrace a national vision more strongly than the majority population.

However, the extent to which members of visible minority groups hold distinctive views about the Canadian federation depends on the province they live in and whether or not they were born in Canada. In Ontario, visible minorities’ views are almost indistinguishable from those of the majority population. In Alberta and in British Columbia, visible minorities born abroad hold somewhat weaker regional grievances than the majority population. However, those born in Canada see the federation in similar terms as the majority population.

The greatest difference between visible minorities and the majority population is in Quebec, where visible minorities born abroad and those born in Canada express considerably stronger support for a national vision. The differences in outlook on the federation between non-French speaking members of visible minority groups and the rest of the Quebec population are particularly striking.

The findings suggest that the federal government’s multiculturalism policy offers a model that appeals to members of visible minority groups. Its highest level of support is among visible minorities in Quebec, whose government has never supported multiculturalism policy and has yet to offer a formal and official alternative.

[conclusion] … If the attractiveness of the federal model appears to exert an influence over visible minorities in Alberta and British Columbia, it might be enhanced in Quebec because of the alternative narrative proposed by the Quebec government. The Quebec government has never officially supported the federal multicultural model and has instead proposed a model of interculturalism that has yet to be stated formally in an official policy and remains unfamiliar to most Quebecers (Gagnon and Iacovino 2007). Our findings thus lend support for those arguing for the Quebec government to adopt an official policy of interculturalism (Rocher and White 2014). A formal policy positioning of the Quebec government on matters of ethnocultural diversity would stand as a symbolic gesture recognizing the contribution of diversity within Quebec society and would promote increased interaction between minorities and the broader population. By so doing, the government could favour a rapprochement between the narrative adopted by visible minorities in Quebec and the dominant one found in Quebec and hence appease some of the tensions that have marked Quebec society over the last few years.

Our final observation concerns an exception to the patterns for all four provinces just discussed. Visible minorities in all four provinces are substantially more prone to see a positive impact of the policy of multiculturalism on Canadian identity than the majority population. This finding is not necessarily surprising considering that, more than any other issue examined in this study, the policy of multiculturalism speaks to the contribution of ethnocultural minorities to the construction of Canadian identity. Moreover, as we argued, the federal government’s multiculturalism policy might be the pivot around which the more federally oriented narrative of visible minorities is structured. Should the growing presence of visible minorities have one significant and consistent impact, it may well be to further strengthen acceptance of the country’s multicultural heritage — in the process further strengthening this pillar of Canadian identity.

https://irpp.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/study-no56.pdf?mc_cid=7023dd89ad&mc_eid=86cabdc518