(Version française disponible ici)

Quebec is different, we know, but not only in language. Its welfare state, including progressive income tax, childcare and low tuition, is well documented. Quebec is also different as far as housing is concerned.

The current housing crisis notwithstanding (fuelled in part by immigration and interest rates), prices in Quebec have remained below those of similar-sized cities elsewhere. The 2021 census reports average monthly rent in Montreal is $981 compared to $1,618 in Toronto, and average house prices are $500,400 and $1,112,000 respectively. The difference cannot simply be explained away by lower incomes. Median income in Québec is now near Ontario’s. The explanation for Quebec’s more affordable housing lies elsewhere.

Affordable Quebec, unaffordable Ontario

To gauge housing affordability, the metric often used is the percentage of income spent on it. Taking 135 urban areas with populations above 10,000 people in Canada, the thirty lowest percentages are in Quebec, with two exceptions. In addition, average rents are systematically lower in Quebec than what housing prices would suggest. Using simple regression analysis, rents in Montreal are 13.3 per cent below what overall housing prices would predict, an indication of a renter-specific advantage.

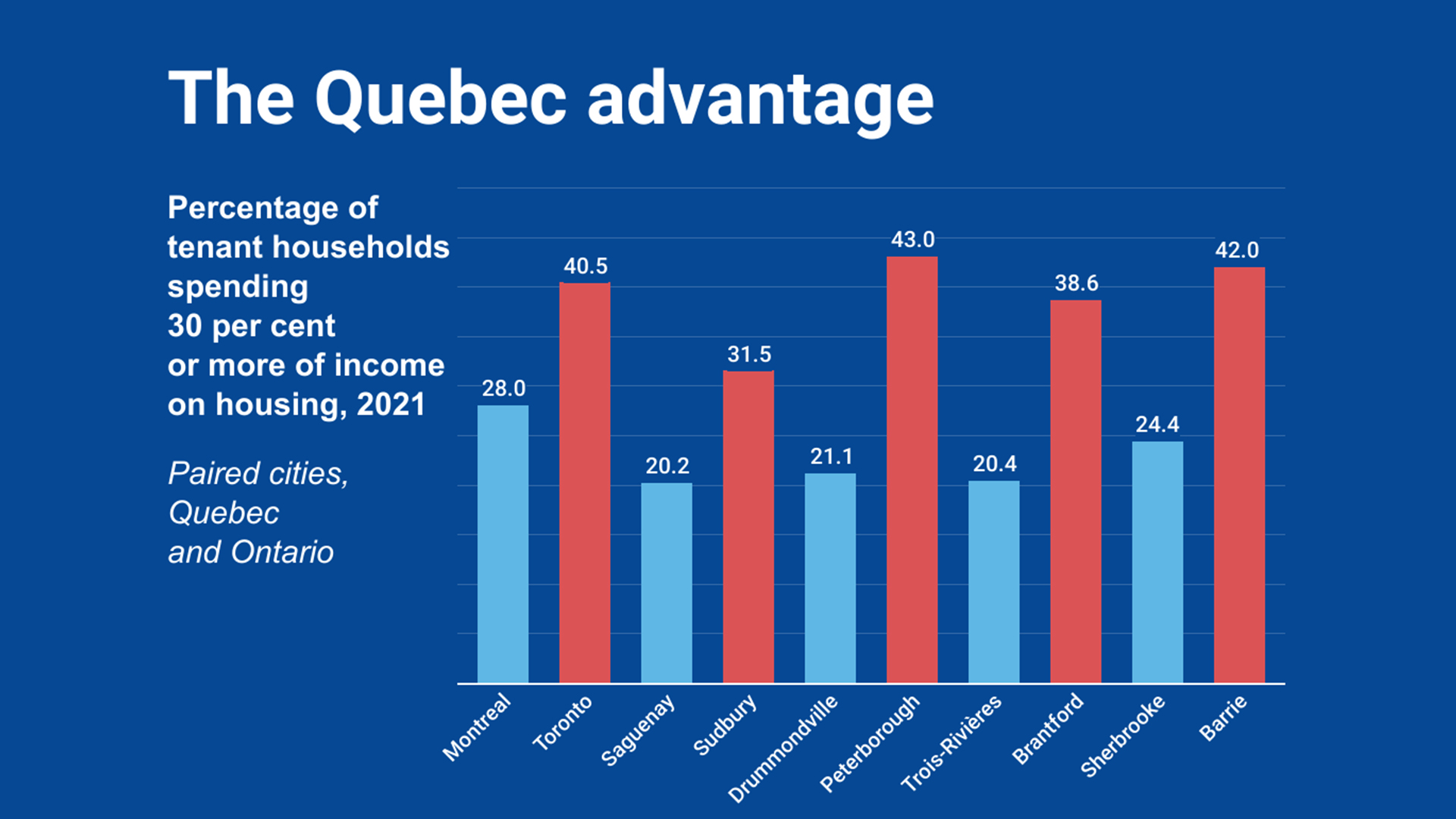

Figure 1 compares housing burdens for paired cities in Quebec and Ontario with similar location and socioeconomic attributes. Drummondville and Peterborough are two prosperous, growing urban centres (metro populations around 100,000) about an hour’s drive from the big city, while Saguenay and Sudbury are two slow-growing, resource-dependent, northern cities. The housing burden was respectively 21.5 per cent and 43 per cent in the two prosperous cities, and 20.2 per cent and 31.5 per cent in the two northern ones. Once again, Quebec comes out on top, as do other pairs of comparable cities.

What did Quebec do right or, alternatively, Ontario do wrong? Social housing is not the answer, as it is less common in Quebec (7.8 per cent of tenants in Montreal, 13.3 per cent in Toronto). It may be that Toronto has more social housing precisely because its housing market is less efficient.

Central financing of urban services vs. development charges

A major urban planning difference is Ontario’s use of development charges levied on developers, in principle to cover the costs of urban services generated by new residential developments (roads, sewage, transit, etc.). Quebec municipalities did not historically have the power to levy charges, except for minor costs such as parks. This prohibition had far-reaching consequences.

In 1989, Ontario brought in the Development Charges Act. The argument for development charges seems reasonable: to make developers pay the social costs of development. What could be more progressive? Development charges would facilitate construction – making development pay for itself – in addition to providing a welcome source of revenue for local governments while lessening pressures on property taxes. Development charges seemed like a good thing.

The true impact was different. It opened a trap door that was difficult to close once opened. Calculating the cost of services generated by residential developments is not an exact science, leaving much room for discretion. The temptation to keep adding on services financed via development charges is difficult to resist. The provincial government loved them too because they allowed it to offload services to municipalities.

This is exactly what happened in Ontario, taking Toronto as a prime example. The development charge effective Aug. 15, 2023, for a two-bedroom apartment is $80,218 per unit, which includes services such as policing, firefighting, childcare and libraries.

The impact on housing was threefold. First, the direct cost was predictably passed on to consumers, renters or owners. Second, since this was an upfront charge, often also entailing drawn-out negotiations with local government, only developers with sufficient resources entered the field. This curbed supply, producing an oligopolistic housing market. Finally, since charges are levied per unit, irrespective of income generated, it created an incentive to build more expensive (often high-rise) units, which explains in part Toronto’s “missing middle.”

Let us return to Quebec, where urban services are largely financed via general property and provincial taxes. The result was a more open market, that facilitated the entry of small developers and the building of the two- and three-story “plexes” that are less costly to build and typical of Quebec cities. Lifestyle preferences were undoubtedly also a contributing factor.

Quebec also lacks Ontario’s legislated greenbelt or the recently enacted provincially significant employment zones, both of which limit the land available for residential development. Overall, Quebec’s housing market has historically been less restrictive than the one in Ontario.

Soft rent control

Quebec’s low rents aren’t only explained by greater market fluidity. Rent control is a political minefield. Finding the right equilibrium between renter and landlord rights – the first a condition of social justice, the second of an efficient housing market – is almost an impossible task. However, Quebec’s soft rent control model seems to come close.

The road Quebec chose typifies its approach to many public policy issues: a mix of pragmatism and social concerns. Under pressure to introduce rent control, a Parti québécois government created the Régie du logement in 1980 to arbitrate relations between landlords and renters. The Régie has since been redubbed the Tribunal administratif du logement (housing administrative tribunal) or TAL.

The founding father of the original Régie, Claude Chapdelaine, was an economist by training with a social conscience, who imbued the organization with a mission to protect renters and also ensure investment in building and improving housing remained profitable. The philosophy has largely remained in place with the TAL.

The TAL’s oversight is limited to dwellings over five years old. Initial rents are set by the market, but the tribunal’s mandate ensures subsequent rent increases remain within an established range. The tribunal also builds on a culture of accommodation, a legacy of the “plex”, where renters and landlords often lived side by side. Rent agreements are generally freely determined, with only a fraction needing arbitration. Because guidelines are public, landlords know they face disputes if they raise rents above published limits. Renters, on their part, know that contesting allowed increases is useless.

The allowable rent increases are continually adjusted. The evidence suggests that the tribunal has largely succeeded in its dual mission of keeping rent increases in check while also encouraging upkeep of the existing stock and new construction: new rental construction in Greater Montreal (units completed) grew at a heathy rate over the last twenty years – until the current housing crunch.

Ontario learns too late, Quebec receives a warning

Last November, Ontario passed the More Homes Built Faster Act, or Bill 23, which as the title suggests seeks to stimulate housing supply. I fear it is thirty years too late. The act proposes several positive steps (i.e., greater flexibility on what can be built), but for the purpose of this article the major innovation is the rollback of the power of municipalities to levy development charges, predictably denounced by Ontario mayors.

However, it is not clear cities have much leeway to significantly reduce development charges. The city of Toronto claims the $80,000 in charges mentioned earlier for a two-bedroom apartment are in accordance with Bill 23. Cities will understandably seek to maintain their revenue despite development charge reductions, given the other unpalatable option is to raise property taxes. Still, if Toronto is any indication of post-Bill 23 development charges, the impact on housing supply will be limited.

Is Quebec about to copy Ontario? Quebec’s Bill 122, passed in 2017, now allows municipalities to levy development charges. So far, few municipalities have availed themselves of this right and the charges have remained modest. It’s not too late to stop the slide into an Ontario-style trap.

Quebec’s planned reform of urban and regional planning provides a unique opportunity to redefine the limits of allowable charges together with, hopefully, a clear strategy for the provincial financing of housing-friendly infrastructure.

In addition, Quebec’s housing reform bill, tabled this year, remains largely true to the founding principles of Quebec’s soft rent control. The TAL’s mandate remains intact, although the bill has predicably been critiqued by both sides of the equation, too landlord-friendly for some, too renter-friendly for others.

However, even the most renter-friendly model or an increased housing supplement for low-income households are of limited use if housing is not built in sufficient quantity and variety. In a July article the Montreal daily, La Presse, reported some $40 million in housing allowances left unused because of a lack of available apartments. Rental vacancy rates in Quebec, especially in smaller urban centres, have fallen below those in Ontario. This is both a sign of sticky housing markets, and a warning that Quebec’s vaunted affordability is vulnerable.