Last week’s Elbowgate fracas in the House of Commons was a study in political masculinity. Trudeau’s impulsive march across the floor, and Mulcair’s aggressive response, played into long-standing narratives about each leader’s masculinity and their fitness for leadership.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has introduced Canadians to a new form of masculinity in Canadian politics. A self-proclaimed feminist, Trudeau is as comfortable paddling down the Bow River in Calgary as he is marching in Vancouver’s Pride Parade.

Describing Justin Trudeau’s brand of masculinity has become something of a national pastime. Throughout the 2015 Canadian federal election, political commentators described the Liberal leader as “emotional”, “boyish”, and “charismatic yet inexperienced”, but also “self-assured”, “quick-minded”, and “earnest”.

His hair, his looks, and his age all became a source for media fodder, a tool for potent political image making and, at times, a political liability for the Liberal leader.

Not that the Liberals have been immune from playing the masculinity game. As Canada’s twenty-third prime minister, Trudeau has received largely positive attention for posing provocatively in Vogue magazine, dressing as Han Solo for Halloween, and inviting the media to watch him train at a boxing gym in New York City.

At the same time, Trudeau’s political opponents have attacked him for his gender presentation almost continually since his selection as Liberal party leader in 2013. The Conservative attack ads with tag lines like “nice hair, though” and “he’s in way over his head” were designed to make Trudeau the butt of a masculine joke.

Crucially, these attacks made both implicit and explicit connections between Trudeau’s masculinity and his fitness for government.

As one senior member of the parliamentary press gallery put it, “There was an attempt by the Conservative Party to paint Justin Trudeau as somehow not masculine — that he wasn’t ‘man enough’ to be prime minister.”

Competing narratives about masculinity have been a prominent feature of our recent politics. With Justin Trudeau’s historic victory last October, perhaps new space has opened for a discussion about gender, leadership, and politics in Canada.

My co-author, Kyle Kirkup, Assistant Professor at the University of Ottawa’s Faculty of Law, and I set about studying masculinity and political campaigns following the 2015 federal election. We noticed how casually the Conservatives and NDP attacked Trudeau for his manliness, using it as a proxy for his ability to lead.

We will be presenting this study for the first time next week at the annual meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association in Calgary. In our study, we conducted an extensive media scan, a series of interviews with Ottawa political consultants and members of the parliamentary press gallery, and an analysis of campaign materials from the 2015 federal election.

In building upon R.W. Connell’s theory of hegemonic masculinity – which underscores how dominant notions of what it means to be man are normalized over time – our study developed a list of characteristics that are often associated with the ideal male politician.

These “traditional” attributes include aggression, competitiveness, confidence, strength, and stoicism.

Ian Capstick, Founding Partner and Creative Director of MediaStyle, described the idealized male politician to us as:

“Clean-shaven; above 6 feet; mildly muscular, not overly muscular; and has a friendly, generalized, generic disposition. That is your ideal politician — who you want to run. The vast majority of any honest political tacticians will tell you that. Hopefully, university educated; clean, straight teeth; hopefully with a wife, 1.5 children, and a dog.”

While a limited number of men are able to embody this ideal version of masculinity, it is the standard against which all others — including women and less masculine men — are judged.

On the other end of the spectrum, men who fail to live up to this idealized masculinity become associated with stereotypically feminine traits or a form of subordinate masculinity.

This type of masculinity is usually associated with traits such as indecision, passiveness, weakness, emotiveness (excepting anger and aggressiveness), and terms of emasculation — being young, boyish, or immature.

In our study, we looked at 756 editorials and opinion pieces published in the ten highest circulating Canadian English-language newspapers during the 2015 federal election. We scanned the articles for uses of traditional and subordinate terms to describe Stephen Harper, Thomas Mulcair, and Justin Trudeau.

What we found was striking.

While political commentators and editorial boards most commonly described Stephen Harper and Thomas Mulcair using terms affiliated with traditional masculinity, Justin Trudeau was overwhelming cited for his non-normative gender presentation.

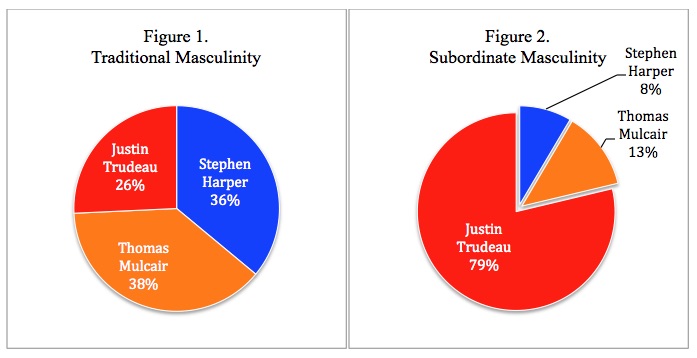

In our sample, we found that terms related to traditional masculinity were, in aggregate, more frequently used to describe Mulcair (38%) and Harper (36%), than to describe Liberal leader Justin Trudeau (26%).

Harper was most frequently described as “strong”, “muscular”, and “tough”, while Mulcair was most frequently described as “angry” or “aggressive”. Trudeau was described as “confident” and “self-assured”, but these terms appeared in the context of articles about his debate performance and were usually discussed as an unexpected trait in the leader.

In contrast, we observed that 79% of subordinate masculine terms in our sample were used to describe Trudeau, while Stephen Harper (8%) and Thomas Mulcair (13%) received significantly fewer such references.

Trudeau was largely described using emasculating and emotive terms. While some of these descriptors were positive — Trudeau was frequently described as “passionate” about the issues — they also undermined his position as the leader of a major Canadian party.

So, how did each leader present his masculinity to the Canadian electorate?

Stephen Harper projected a mix of 1950s suburban dad and the stereotypical tough guy. Described by political commentators variously as “tough” on crime, terrorism, Russia, and the economy, pundits found Harper’s approach to politics to be “strident” and “consistently strong.”

At the same time, John Ibbitson described Harper in his 2015 book on the former prime minister as “the ordinary guy, the family man who gets his coffee at Tim Horton’s (or would, if he drank coffee) and his hamburgers at Harvey’s. A hockey dad.”

In an interview for our study, Susan Delacourt echoed this characterization of Harper as a family man — a key aspect of the idealized masculine politician. As she described his masculine persona: “Harper was very much the 1950s dad.”

Harper’s persona brought together a traditional form of masculinity with a set of policies on the military, the Arctic, and a Conservative narrative of Canadian history to form a coherent political package.

The relationship between Mulcair and aggressiveness is marked. Frequently described as “Angry Tom” in the Canadian media, Mulcair’s assertiveness and temper were portrayed as both as an asset during Question Period in the House of Commons, but also a liability for his likability as a national leader.

Fearing for his likeability, the NDP sought to shift Mulcair’s persona away from aggressiveness and towards a softer, grandfatherly demeanour.

The strategy backfired, according to Justin Ling, political reporter for Vice Canada:

“They forced Tom Mulcair into this role that he was very uncomfortable in — being this smiling, happy, suburban dad. It just didn’t play well. He is a passionate guy, a guy that sometimes gets angry, and to force him to pretend that he is this smiling, happy, friendly, ‘neighborino’. It doesn’t work. It made him look creepy, it made him look disingenuous, it made him look fake. And people picked up on that.”

An authentic gender presentation is therefore an important feature of traditional masculinity. By recasting Mulcair’s masculinity in an inauthentic way, the NDP contributed to a growing unease among the Canadian voting public with Mulcair and his leadership.

Finally, the Liberals countered the attacks on Justin Trudeau’s masculinity by underscoring their leader’s masculine strengths. As Elise Maiolino argues, his famous 2013 boxing match against Conservative Senator Patrick Brazeau is an early and prime example of image-making designed to “recuperate” Trudeau’s masculinity. She goes on to argue that Trudeau’s win against Brazeau enabled a “shift from precarious masculinity to an earned hegemonic masculinity” for the Liberal leader.

This shift would prove impermanent, as our study demonstrates, and something the Trudeau campaign had to address in its own advertising throughout the 2015 election. The images they created — Trudeau paddling down the Bow River, climbing the Grouse Grind, walking up an escalator, training in a boxing ring — came to define the future prime minister as a confident and self-assured leader.

Some political observers may be inclined to conclude that Justin Trudeau’s victory in the 2015 election signals the beginning of a new era in the history of masculinity and Canadian politics. At the very least, it suggests that hewing to forms of traditional masculinity is not the only path to victory in Canadian politics.

Indeed, our study provides preliminary support for this proposition — while Justin Trudeau’s opponents, along with the Canadian news media, tended to associate him with notions of subordinate masculinity, he led the Liberal party to a historic majority government during the 42nd federal election.

While we welcome the emergence of a new political landscape, one where leaders have an opportunity to flourish, regardless of their gender, sexuality, race, or class position, only time and further research will tell whether we are in the midst of a watershed moment in the history of gender and Canadian politics.

Photo: Canadian Press / Jonathan Hayward

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.