Relentless technological change is everywhere. So it’s natural to assume that our economy is more dynamic now than decades earlier. These three propositions seem almost self-evident:

- There’s more firm entry and exit now because the business world moves faster, global competition is tougher and product cycles are shorter.

- On firm entry, there are more new, small start-ups now because technology makes it easier to establish a new business.

- Labour turnover is higher now because workers change jobs more often — either due to increased layoffs or simply because today’s workers are far less likely to spend their career with the same employer relative to prior generations.

Despite these strongly-held narratives in our media, the research actually shows that Canada has less firm entry and exit, fewer start-ups, and no increase in job turnover or layoffs, relative to the past.

While the reasons behind these trends are unclear, this research has some important implications that need attention. First, let’s review some recent findings.

Firm entry and new start-ups

A new discussion paper by Bank of Canada researchers documents some important, puzzling and potentially depressing trends.

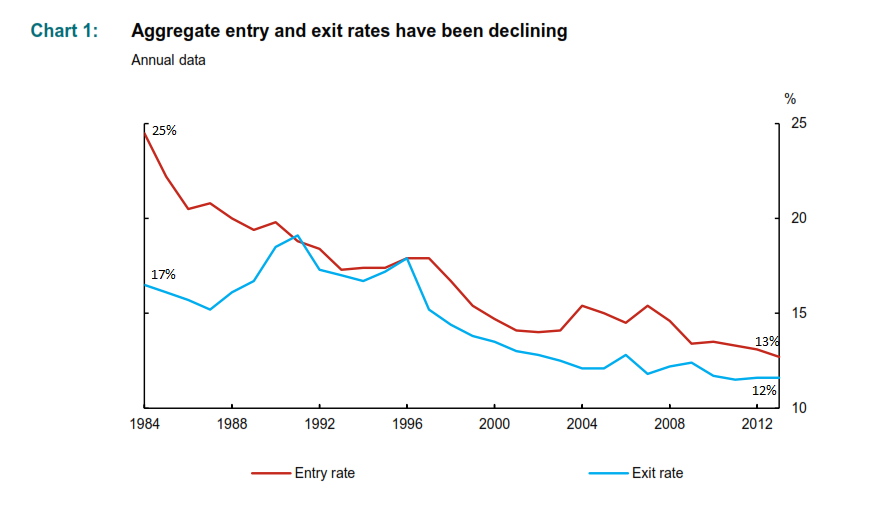

Firm entry and exit rates have fallen significantly in Canada over the past three decades:

Entry has fallen more than exit. Firm entry matters because it is typically associated with productivity growth, new ideas and technological adoption; firm exit matters because it is often associated with driving out inefficient businesses.

Entry has fallen more than exit. Firm entry matters because it is typically associated with productivity growth, new ideas and technological adoption; firm exit matters because it is often associated with driving out inefficient businesses.

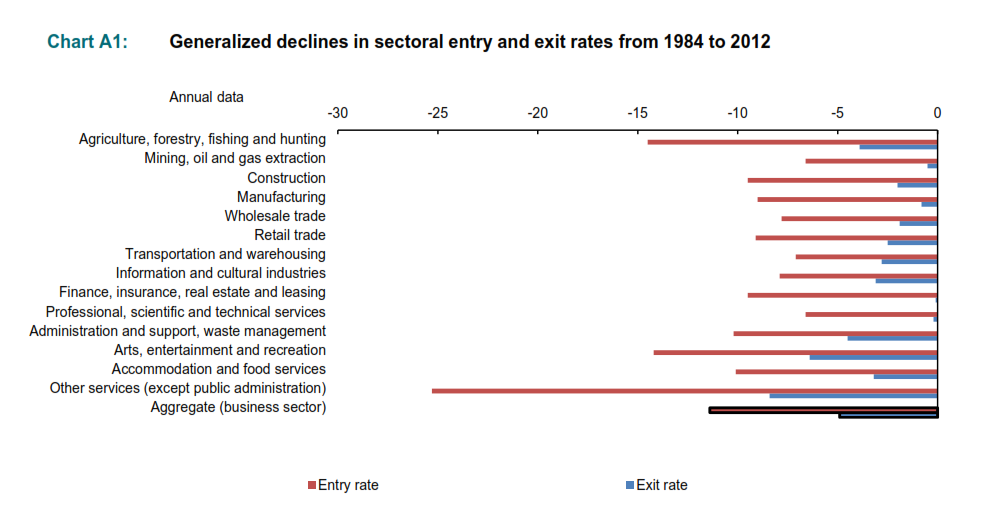

These declines aren’t just confined to a few industries, but are broad-based:

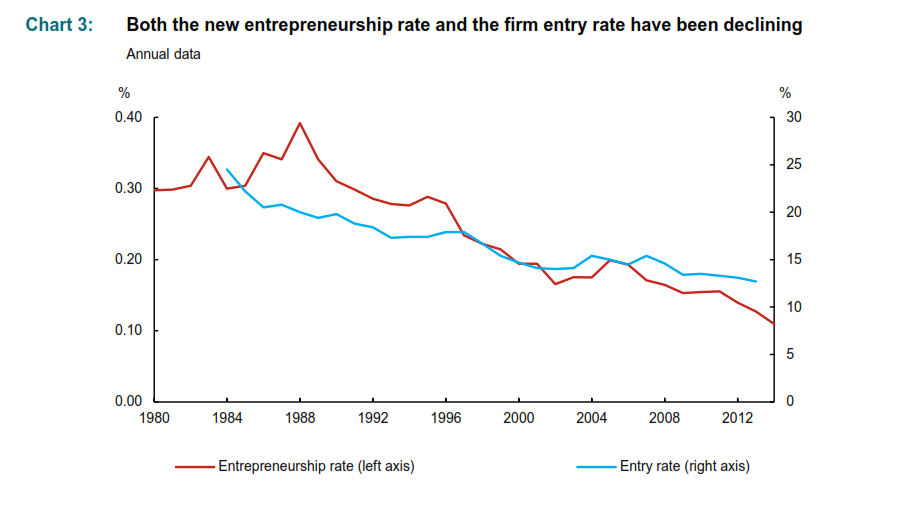

The Bank’s research drills down into this fall in firm entry by focusing on small “start-ups” — the new entrepreneurship rate (the red line in the figure below, identified in the Labour Force Survey as individuals who report being self-employed for one year or less, who hired paid help for their businesses, as a fraction of the working age population).[1] This series is also falling, even faster than the overall firm entry rate (blue line).

The Bank’s research drills down into this fall in firm entry by focusing on small “start-ups” — the new entrepreneurship rate (the red line in the figure below, identified in the Labour Force Survey as individuals who report being self-employed for one year or less, who hired paid help for their businesses, as a fraction of the working age population).[1] This series is also falling, even faster than the overall firm entry rate (blue line).

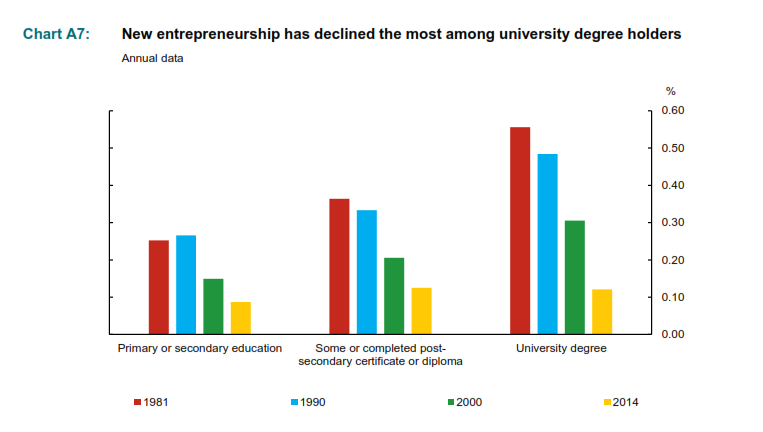

Interestingly, our new entrepreneurship rate fell for all education groups, particularly university degree holders:

Interestingly, our new entrepreneurship rate fell for all education groups, particularly university degree holders:

… for men and for women, and in all regions of Canada.

… for men and for women, and in all regions of Canada.

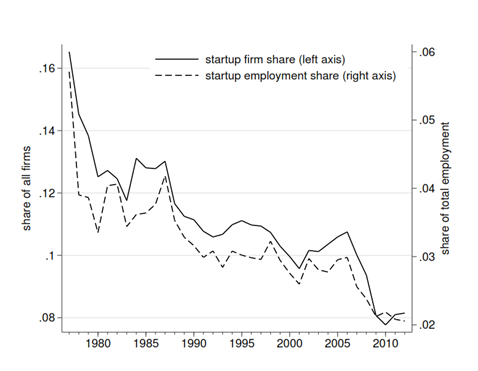

We aren’t alone. The US — often considered the world’s most dynamic economy — also experienced similar trends, identified in the New York Fed’s research:

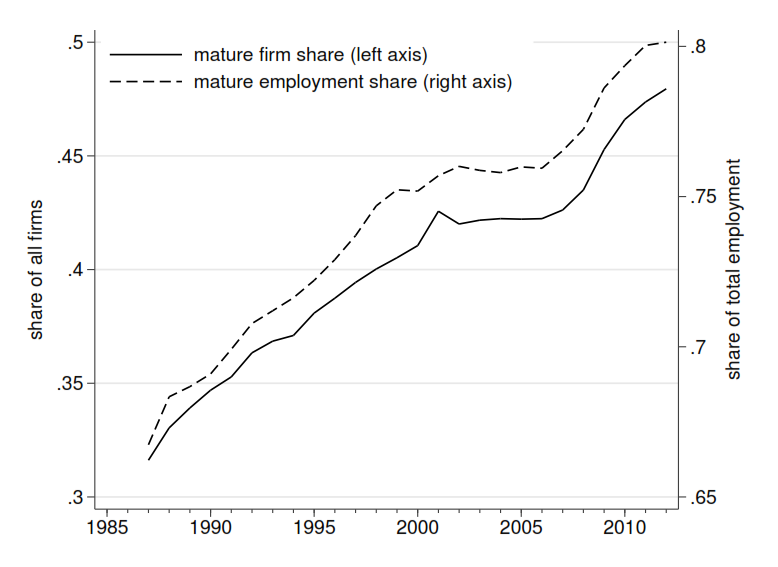

This US research also reveals that firms are aging much like the population. Essentially, fertility rates fell (where firm fertility = start-ups), so the population (of firms) ages over time:

This US research also reveals that firms are aging much like the population. Essentially, fertility rates fell (where firm fertility = start-ups), so the population (of firms) ages over time:

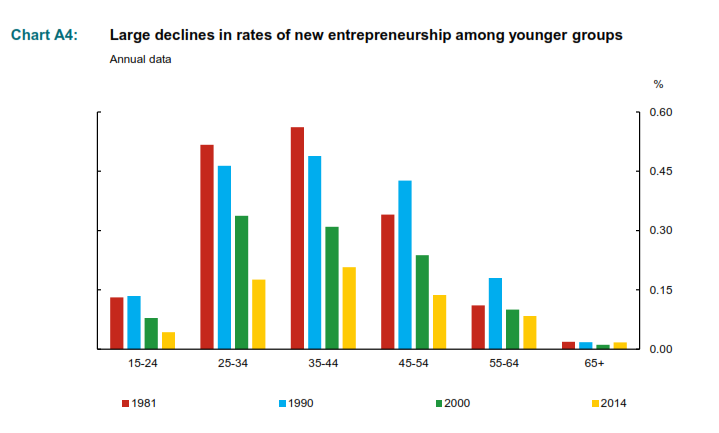

Importantly, while the aging workforce is likely a contributing factor — since younger people are more likely to start businesses — it isn’t close to the whole story. (Nonetheless, demographics factors have played a bigger role in Canada since 2000, and will likely continue to reduce entrepreneurship in the next few decades.)

Labour market turnover

Labour market turnover

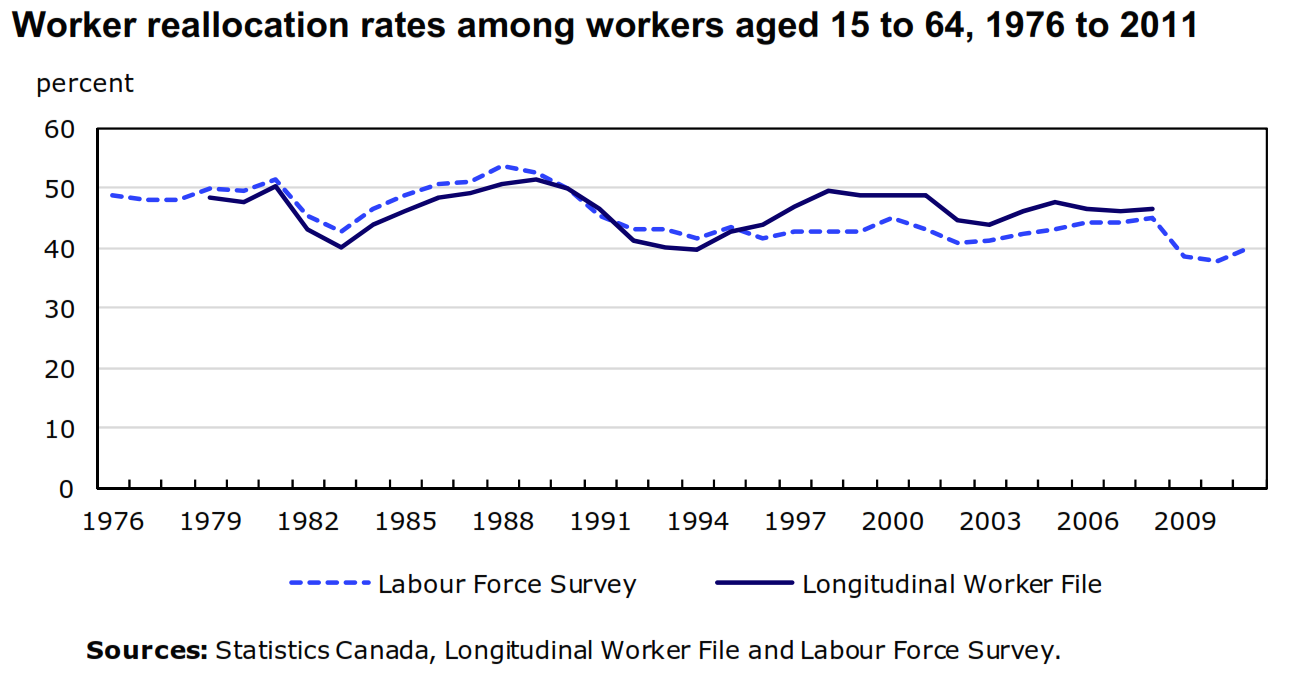

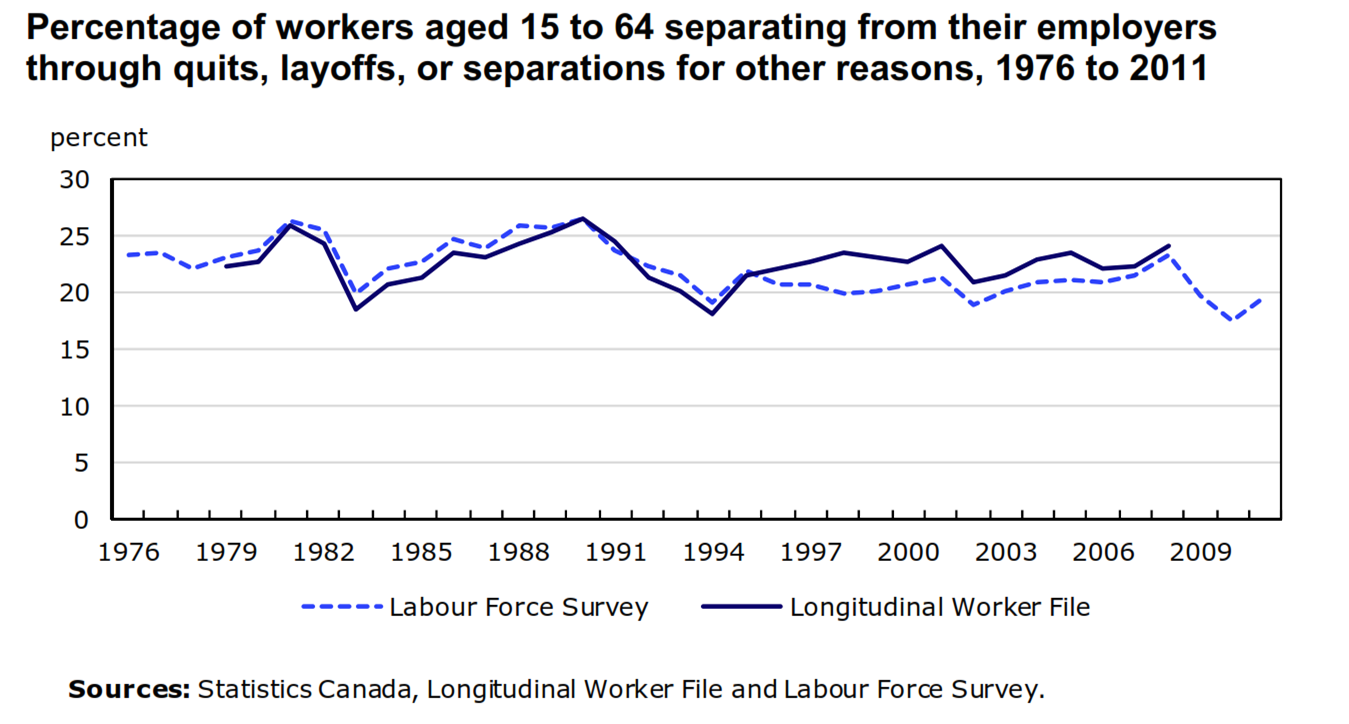

Turning to concerns about increased labour market churn, perhaps surprisingly a Statistics Canada paper finds that the rate of worker reallocation — the share of turnover in the labour force due to hiring and job separations — hasn’t increased in Canada over the past three decades. As the chart below shows, while turnover rises and falls cyclically, it displays no real long-term trend. (By comparison, US research shows a more substantial drop in job turnover.)

Of this labour reallocation, the long-run trend in job separations[2] has been essentially stable.

Of this labour reallocation, the long-run trend in job separations[2] has been essentially stable.

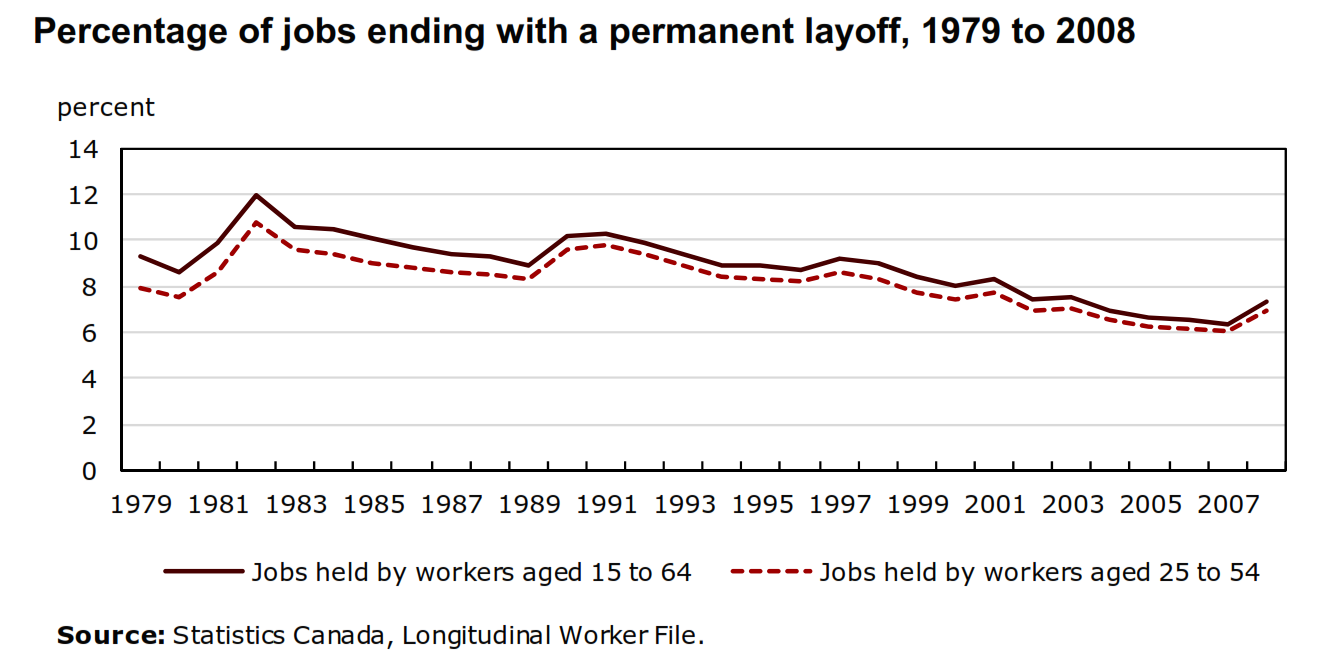

And among a key sub-component of these job separations, the rate of permanent layoffs has actually trended down in Canada prior to 2008 (notwithstanding the recessionary spikes).

And among a key sub-component of these job separations, the rate of permanent layoffs has actually trended down in Canada prior to 2008 (notwithstanding the recessionary spikes).

None of this says that the share of non-standard employment hasn’t increased or that labour market adjustment has been painless. For example, Canada’s manufacturing sector, like in other countries, has clearly experienced layoffs and separations that haven’t been matched by new hiring. This has had important effects in communities where manufacturing has traditionally been dominant.

None of this says that the share of non-standard employment hasn’t increased or that labour market adjustment has been painless. For example, Canada’s manufacturing sector, like in other countries, has clearly experienced layoffs and separations that haven’t been matched by new hiring. This has had important effects in communities where manufacturing has traditionally been dominant.

When assessing the overall picture, the difference between these aggregate results and what’s happening below the surface is important, as the study notes:

During the 2000s, worker reallocation varied substantially across industries and firm sizes, as small firms and low-wage industries exhibited both relatively high hiring rates and high separation rates. Worker reallocation also varied markedly across age groups, as young workers were hired and separated from employers much more frequently than their older counterparts.

These overall results probably aren’t the picture of economic dynamism that you expected. Here’s the thing, this research documents what happened, not why.

We don’t know whether the future holds a different path. With automation and robotics, many scholars rightly question whether future labour demand will result in more labour market disruptions than in the past and what this might mean for inequality and redistribution.

We also need to consider how people acquire and apply skills, whether they’re transferable across sectors, and whether opportunities are broadly held and succeed in stimulating innovation.

Diagnosis needed before prescriptions

Economists often attribute puzzles such as these to problems with data measurement. It’s possible that technological change means that in some industries, new start-ups (like Facebook or Google) required far less labour than in the past. However, the Bank of Canada’s research covers those who hire any additional staff, so there’d have to be a big increase in single-person businesses to offset this finding, which seems unlikely.

If measurement isn’t the obvious explanation, then we need to search for factors that have raised the costs of firm entry and/or lowered the benefits, or changed the incentives to stay in our jobs versus switching track. Various authors offer different explanations, some are potentially good news; some are bad.

On the positive side: improvements in the labour market may have raised workers’ outside options — unemployment rates are down, real wages are up, and work arrangements are becoming more flexible. As a result, perhaps some workers don’t feel compelled to start up their own business.

Alternatively, maybe we now have a much more concentrated market structure in some industries in Canada — like the retail sector, banking or telecoms — where huge up-front costs make it harder for start-ups to compete against established brands.

Whatever the diagnosis, we think that Canada’s “start-up slow-down” raises some big picture concerns. Perhaps most significant is the decline in entrepreneurship among younger and more-educated cohorts. Research suggests that peak innovation (starting a business, research, patenting ideas, etc.) typically occurs when we’re younger.

Although startups are just one element of the many ways in which innovation happens, if younger workers are less inclined today to be entrepreneurs than their parents we need to ask some fundamental questions:

- Are our learning institutions encouraging entrepreneurship?

- Are we teaching the skills needed to undertake innovations in today’s more knowledge-intensive economy?

- Have we become a more risk-averse society?

We don’t have answers, but it’s a discussion Canada needs to have.

Being an entrepreneur obviously isn’t for everyone – it requires some specific skills and traits – but if we want to renew ourselves with the lifeblood of new and productive ideas, then we need to ensure Canada has a creative, inquisitive, and risk-taking workforce.

Reduced firm and labour turnover may well be contributing to our weak productivity performance and slowing trend economic growth. Politicians should take note of these findings because there’s evidence that slower firm entry slows job creation, and reduces trend employment growth.

(Conversely, one up-side of having older firms is that while employment growth is slower, it should be become less volatile, since start-ups are more cyclically-sensitive than older firms.)

Our policy-makers need a better handle on what’s driving the slow-down in the dynamism of Canada’s economy. Being more innovate and productive are key parts of how we must respond to a future of slower labour force and economic growth. We need to figure out why the Canadian economy seems less dynamic, and what can ultimately be done to improve the situation.

[1] While new firms are often small firms, they need not be. For instance, think of the entry from established foreign businesses, like Target, which tried and failed to enter the Canadian retail sector.

[2] Job separations includes quits, layoffs and separations for other reasons such as returning to school or caring for family members, etc.

Photo: Pete Spiro / Shutterstock.com