The federal government’s new balanced budget legislation will be among the strictest in the country… or that we’ve ever had. But is it a solution in search of problem?

In 2013, the federal government announced that it would introduce balanced budget legislation. Last week, after much speculation about its contents, the Balanced Budget Act was revealed in Bill C-59.

This blog examines the proposed law, compares it with similar rules used by the provinces, and considers the broader need for it.

What’s in the law?

The new law will apply to the current fiscal year of 2015-16 and beyond. It requires balanced budgets or better each year except in extraordinary situations — defined as adverse developments that cost the federal government at least $3 billion in a fiscal year due to a natural disaster, significant national emergency, or (threat of) war.

Whenever a deficit is projected or recorded, the Minister of Finance must appear before the House of Commons to explain why and present a plan to return to balanced budgets. This plan must include an operating wage freeze for all government entities and a pay freeze for the Prime Minister, Ministers and Deputy Ministers in the case of a recession (in the case of a deficit outside of a recession or extraordinary circumstance, they incur a pay reduction of 5%).

The law also requires that any surplus must be applied to reduce the federal debt. This means that the government can’t build up a buffer in a ”œrainy day fund” — as some provinces allow — by running surpluses in good times that could be drawn down to cover deficits in bad times that would not otherwise invoke an escape clause.

This sounds like a stringent law, and as I’ll show below it is, but there’s still some potential wiggle room as the plan for this fiscal year demonstrates. Nothing prohibits revenues from including one-time gains from the proceeds from asset sales. Moreover, there’s no account taken for off-balance sheet items that could ultimately raise debt levels despite running a “balanced budget”, as is planned in this fiscal year due to losses from other comprehensive income.

And because all rules can be gamed, there are even more obscure and perverse ways that a future government might avoid breaching this law. They could, say, pay more in the case of a flood than is strictly necessary in order to cross the $3 billion threshold and trigger the ”œextraordinary circumstances” clause to excuse a deficit. Or they might boost military spending on a procurement item and cite the threat of war, etc.

How does this law compare to others in Canada?

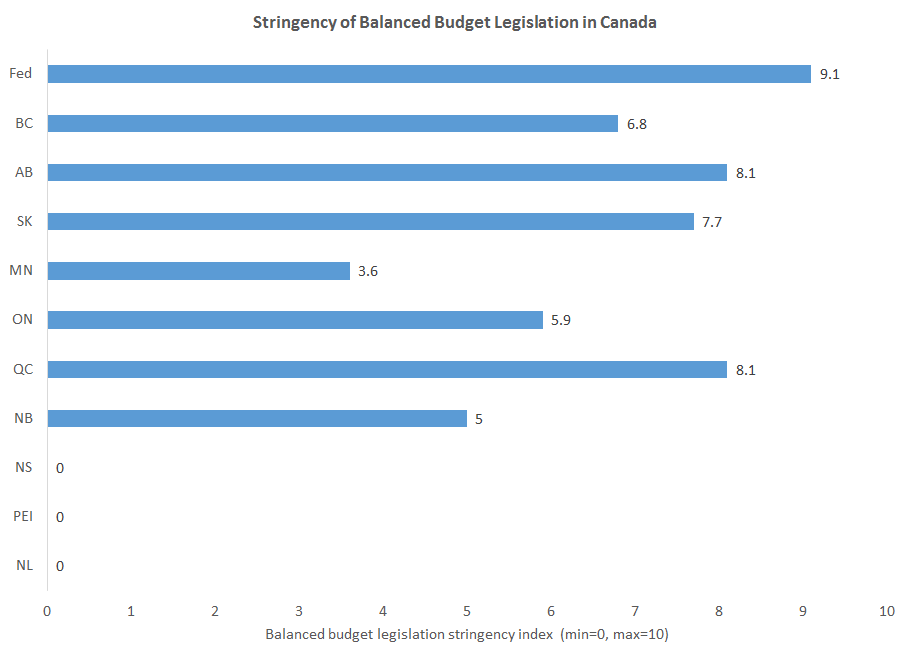

Comparisons of these laws across jurisdictions and over time are difficult and imperfect, but in past research I developed an approach to quantify the stringency of balanced budget legislation for Canadian provinces based on five factors (whether the law prohibits forecasting or running a deficit, the time allowed to return to balance, the escape clauses, actions required if breached, and penalties imposed).

Using this methodology, the new federal law scores a 9.1 out of 10, where 10 is the most stringent used in Canada and 0 means there’s no rule. Compared with the 25 other related laws that have been used federally and provincially since 1989, the new federal law is tied for the second most stringent ever used.

(Manitoba’s Balanced Budget, Debt Repayment and Taxpayer Protection Act from 1995 scores the highest at 10. It included many similar features, such as salary reductions and public hearings to explain any deficit, but also required any deficit to be offset in the next fiscal year — whereas this federal law requires a plan and a timeline to return to balance that could exceed one year.)

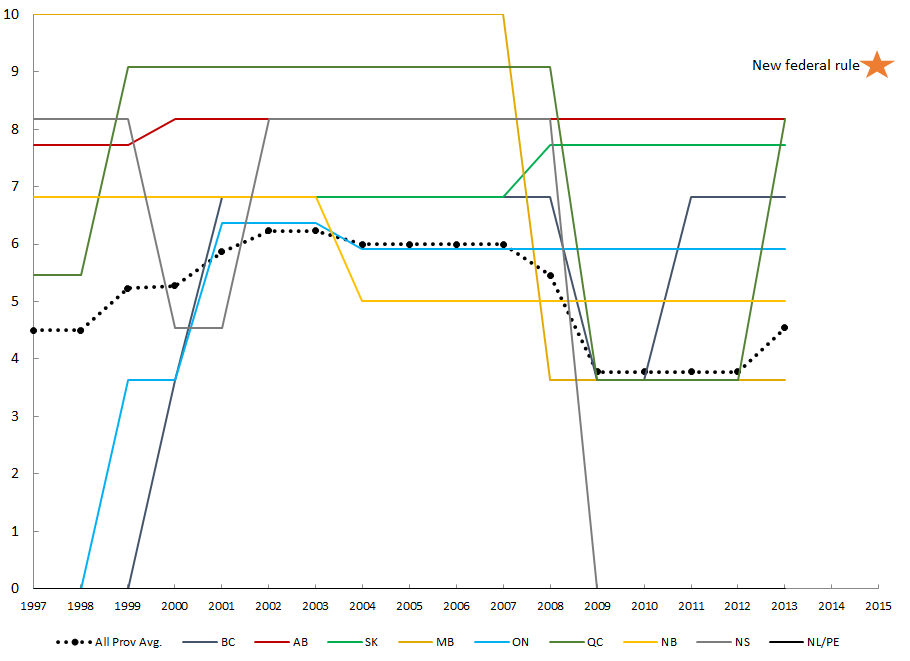

Two co-authors and I (Michael Atkinson and Haizhen Mou of the University of Saskatchewan) are currently researching the impacts of balanced budget legislation in Canadian provinces after the global recession. This on-going and preliminary work would suggest that this new federal law will be the strongest in Canada when it comes into effect, relative to the rules that provinces were using in 2013.

This is how it compares with the laws used in these jurisdictions since 1997.

Does the federal government need this law, in this form at this time?

This raises a broader issue of whether this law is needed, and if it is, whether it needs to be this strict.

If this rule remains in place for a while, it will likely improve federal government finances (relative to not having this rule in place). However, I’m not convinced that bettering federal finances is among our highest priority policy issues right now.

Few, if any, serious budget watchers are overly concerned about Ottawa’s long-term fiscal outlook — which our best estimates suggest is on a sustainable track — and only a small minority of pundits on the right are currently recommending what this law aims to: balance the budget this fiscal year and for the foreseeable future, except in rather extreme circumstances.

In a previous post, I suggested that the feds could run small deficits over the medium term of about 1% of GDP per year without increasing the debt-to-GDP ratio, and that this may be a sensible alternative given the current circumstances. In decades past, I’d probably have considered that suggestion heretical, but I now think that five important factors have fundamentally shifted since the 1990s public debt crisis in Canada when these types of balanced budget rules were initially and widely adopted:

1. Canada’s public debt as a share of the economy has fallen significantly and is now relatively low by historic and international standards;

2. Long-term interest rates have also fallen to a surprising degree, which alters the incentives for spending versus saving/debt repayment;

3. Trend economic growth has slowed due to population aging and weaker productivity, which increases the premium on even marginal improvements in growth;

4. Monetary policy-making is in new and largely uncharted waters. The ”œzero lower bound” has become a far bigger issue, policy interest rates have been held lower-for-longer — even negative in some countries, which was previously considered impossible — while we’ve increasingly used more exotic policies such as quantitative easing whose longer-term impacts and exit strategies are not well-understood;

5. Research since the global recession suggests that fiscal policy can be much more effective at boosting economic growth than was previously-believed when monetary policy is impaired — as it essentially is now.

This combination of factors, together with the provinces’ tight overall fiscal policy stance, has me questioning whether Canada’s macro policy approach should be pushing more on fiscal policy federally and relying less on monetary policy.

I don’t have a grand fiscal plan, and we should certainly think harder about the details and be cautious about practical problems that might be encountered, but I think we should focus more on crucial long-term infrastructure investments that probably need doing anyway, that might boost growth, and that could be financed at essentially negative rates (given where 10- to 30-year government of Canada bond rates sit, and assuming we hit our current 2% inflation target annually going forward).

Getting more of a push from federal fiscal policy right now might allow us to rely less on monetary policy ”œinsurance”, which seems unlikely to materially boost economic growth in the near-term, and instead to encourage excessive household borrowing, lower the longer-run return on savings, and incent riskier financial sector behaviour as investors seek higher returns, including by pension funds and those in the shadow banking sector.

*************

The new federal balanced budget law looks like it will among the toughest we’ve had in Canada. This may seem odd when you consider that the federal government’s long-run fiscal outlook is reasonably positive. We may well want to constrain policy-makers and structure a system to preserve the hard-fought fiscal gains that have been achieved, but the patient doesn’t look sick and this seems like stronger medicine than is required.

Photo by Steve Smith / CC BY-NC 2.0 / modified from original