My last post considered the competition for talent among cities and some limits of policy interventions. This one addresses competition for talent, with a focus on what it reveals about inequality.

Relative rankings and perceptions of fairness influence who gets paid what – particularly for those at the top of their fields, who have strong bargaining power.

They’re already rich, yet they want more. The industry’s top performers demand the highest pay in their field or they feel taken advantage of. And, of course, many people may think they’re the best.

Wage competition is a force for good when it encourages a more equitable distribution of profits between workers and owners. But sometimes it simply bids up the level of wages at the top of the distribution, without changing the relative rankings that often matter more for job satisfaction.

And when there’s a fixed pie to bargain over (e.g., when pro sports leagues limit total player salaries), more money directed to the top stars means less money for the bottom of the distribution. As a result, inequality increases as the super-rich pull away from the rest.

Incentives for competing pay packages among the well-off are sharpest when the pay of similar workers is public information. This situation applies in the private sector (e.g., CEOs, entertainers and pro athletes) as well as the public sector (such as when “sunshine laws” effectively require salary disclosure for professionals, such as doctors and university professors).

Simply knowing what other people make can lower aggregate job satisfaction. For instance, this study suggests that wage ignorance is bliss: poorer-paid people are less satisfied with their jobs after they learn of their lower relative pay, while higher-paid workers are no happier to find out how others are doing.

People judge themselves relative to a reference group. If this group is comprised of richer people, you can still be unhappy with your pay, despite being rich yourself.

I think these motivations and labour market dynamics are nicely illustrated by LeBron James’ recent ”œDecision 2.0”. This article reports that a key reason, among others, that LeBron will move to Cleveland next season ”” for a $21.6 million annual salary ”” is that he was tired of being underpaid.

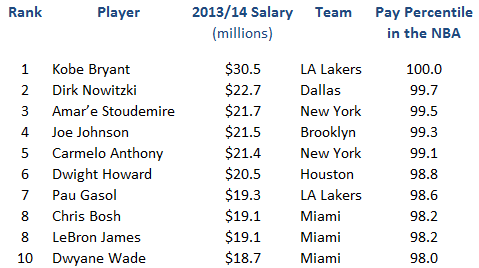

Despite this windfall, James still isn’t the NBA’s highest paid player. Not by a long shot. The table below shows that last season his salary ranked 8th in the league. This put him in the 98th percentile, or the top 2% of NBA players.

Source: Author’s calculations from https://www.sportscity.com/nba/salaries/

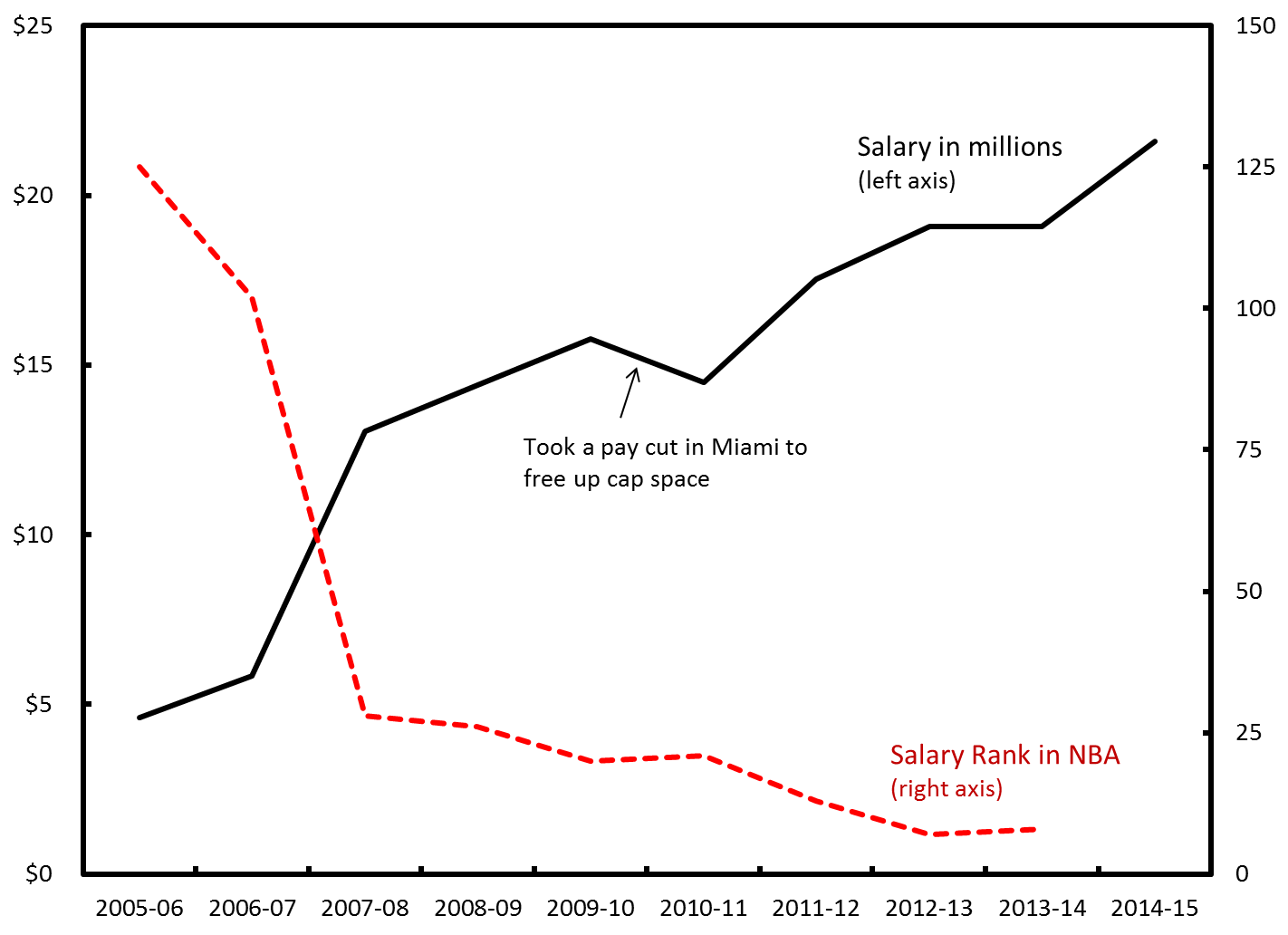

Over the past decade, LeBron’s pay has increased dramatically (see the black line in the figure below, which grew at 18.7% per year in nominal terms, on average), causing his salary ranking within the NBA to significantly improve (red dashed line). Yet he still doesn’t earn the world’s highest salary for a basketball player. That appears to bother him. And an unrelenting desire to be number 1 can be a strong motivator for people near the top.

Source: Author’s calculations from https://espn.go.com/nba/salaries

Pro sports leagues have strategies to keep a lid on spiraling top-salaries: they use salary caps to link overall player payrolls to league revenues. In the case of basketball, the NBA imposes a ”œluxury tax” when a team’s payroll is too high. After James’ last coordinated move to Miami (when he took less than the league’s maximum salary to leave payroll room for other players), the team had 3 of the league’s 10 highest-paid players.

So if his previous move to Miami was driven by a desire to win championships, it seems this move from Miami was more about increasing his pay and positioning himself for an even better deal in the future.

Now that he’s proven himself by winning two championships and playoff MVPs, James can earn a higher salary by leaving Miami. And by signing a short-term contract in Cleveland, he’ll have a credible threat of leaving. This will allow him to take advantage of higher top-end salary rules that are expected in 2016-17 ”” when a new TV deal will likely raise league revenues, which would increase the salary cap.

Photo by Keith Allison / CC BY-NC 2.0 / modified from original